Here’s one from the department of part-of-a-home-builder’s-job-is-to-help-people-not-shoot-themselves-in-the-foot.

This is not brain surgery. A home buyer who buys a new home today that renewably produces as much energy as it uses can save tens of thousands of dollars–all in–on the cost of owning and operating that home. A home buyer whose choice is not to buy such a home because the price tag of getting one equipped to operate at that level of energy performance is too high is missing out.

A Rocky Mountain Institute analysis out today explodes a myth: The widely held view among home builders that building new homes to Zero Energy (ZE) or Zero Energy Ready (ZER) performance levels would price out too many potential buyers.

A National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) 2017 survey found that 81% of single-family home builders either don’t know how much more it will cost to build a green home or thought green home building would add more than 5% to the cost, while 58% think consumers are willing to pay less than a 5% premium for a green home. Consumer research yields a similar result for home buyers. These perceptions are preventing or disincentivizing stakeholders from acting in their own long-term interests.”

The RMI report notes that, currently, ZE and ZER homes represent less than a rounding error in the total stock of U.S. homes–below 0.1% of the market. At the same time, against this very very low baseline, growth has been exponential. The Department of Energy’s Zero Energy Ready Home program forecasts more than 100% annual growth in 2018 for a third year running.

Importantly, the RMI report notes that the learning-curve of building technologies and construction tactics lead to lower added costs for ZE homes, to a plus 3%-to-5% by 2030. That compares with incremental costs today that range from 6.7%-to-8.1%.

Lowering the cost barriers may help with adoption and traction, but the RMI recognizes too that raising the level of urgency and desire among policymakers, builders, and consumers will be the only way to sustain progress.

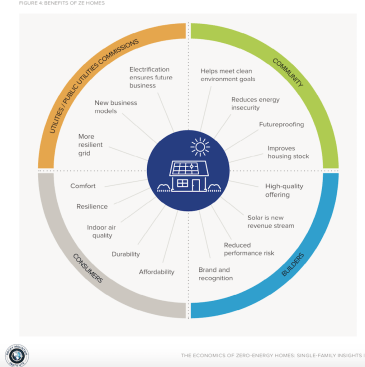

The evident benefits and value of ZE and ZER–to both the planet and people’s monthly-mortgage-payment pocket books, as well as to the business interests of the grid and the local economic interests of municipalities, etc.–are numerous and compelling.

However, these days, costs–particularly “first costs” that impact either the size of a down payment required, or the monthly principal mortgage payment a buyer takes on–are all the rage. They’re all going up–land, borrowing costs, building materials costs, labor cost–the litany is a broken record, and there’s no apparent relief in sight. So, it’s understandable that many builders regard adding an incremental–and unnecessary–cost to a new home’s price tag as defying common sense.

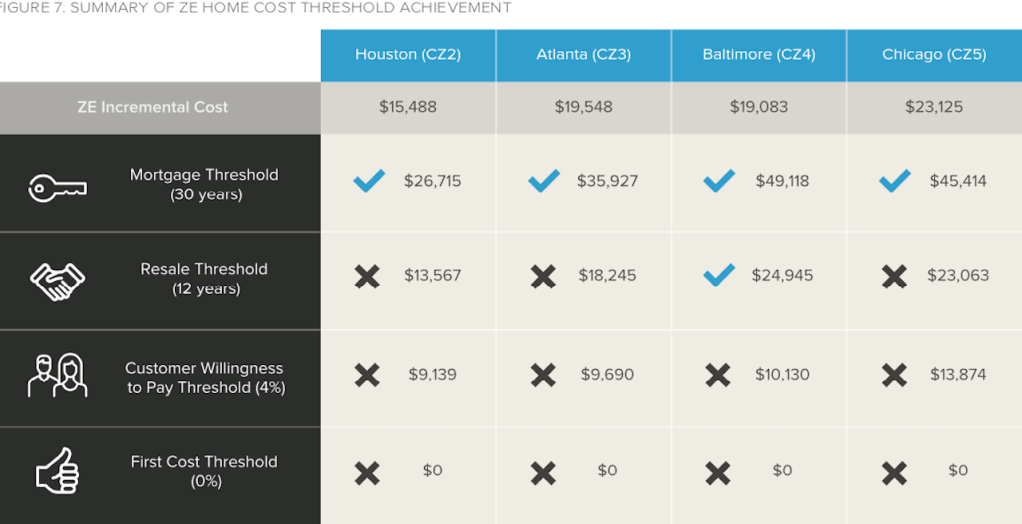

The RMI analysis–reckoning with the understandable push-back from builders–unpacks the real data on what tolerance points are what for consumers, when it comes to weighing the opportunity to pay less in the long run by paying more upfront for a ZE home. Here’s how they look at it:

Consumers Willingness to Pay Threshold: This threshold compares the incremental cost to build a ZE and ZER home (compared with an identical home that meets local energy code) with the first cost premium customers have stated they’re willing to pay in consumer research. According to the latest NAHB research, 42% of consumers are willing to pay a 4% premium for a green home, and 51% of consumers are willing to pay a 4% premium for a ZE home, according to an Opinion Dynamics survey performed in California. Another study by NAHB found that consumers would be willing to spend an average of $10,732 more for every $1,000 in annual energy savings, which roughly translates to a 3.9% incremental cost. Although none of these consumer WTP metrics perfectly represents how much more consumers nationally would be willing to pay for a ZE home, combined they point to a similar threshold that people would be willing to pay for a ZE home–roughly a 4% premium.

In a moment in home building economic history where challenges on the cost and capacity constraint side of the business loom so prominently, the thought of testing or stressing price tolerance levels is excruciating.

It means a change of mind and heart, not only on the part of builders, but their customers, policymakers, and the mortgage finance business community, to looking at value, and total cost of ownership rather than shooting ourselves in the foot by focusing on first cost only.