For the past few years, the top economic challenge for builders was the cost and availability of labor. Access to lots also acted as a constraint on home building activity. For 2018, another supply-side L—lumber—has taken the top slot as the most significant headwind. While labor and access to land will remain challenges for the industry, higher lumber prices are now a greater economic concern.

As builders know, the price increases for lumber have been dramatic. As of mid-May, the Random Lengths Framing Composite Price had increased 15% over the last month, 39% over the last year, 59% since the start of 2017, and 78% since the start of 2016.

These price hikes have had significant impacts on the costs of construction and the pricing of new residential units. For example, NAHB analysis finds that these cost hikes have increased the sales price of a typical newly built single-family home by about $9,000 and the cost of a typical apartment by more than $3,000. Keep in mind that a $1,000 increase in the price of a new home “prices out” approximately 150,000 households from qualifying for a mortgage. So the current run-up in lumber prices has now priced out more than 1 million households from being able to buy a newly built home.

The price of lumber has increased for a number of reasons, including a lack of rail cars in Canada, beetle issues, seasonal demand increases, and a lack of truck drivers and trucking capacity. However, the most important factor for recent gains is the imposition of an effective 21% tariff rate on Canadian softwood lumber.

Along with proposed tariffs on steel and aluminum, these tariffs act as taxes on Americans, essentially undoing some of the economic benefits of last year’s tax cuts. In the case of softwood lumber tariffs, the tariff is a tax on home buyers, renters, and the residential construction industry. Because of this, NAHB is strongly advocating for the administration to quickly resolve the trade dispute to ensure an adequate supply of lumber at reasonable market prices.

As part of the effort, I joined an initiative to warn of the direct and the macroeconomic costs of tariffs. Organized by the National Taxpayer Union, this push led over 1,000 economists to sign a letter opposing increases in tariffs. At a press conference, I noted the harm lumber tariffs in particular are having on the housing market, as well the macroeconomic risk they present.

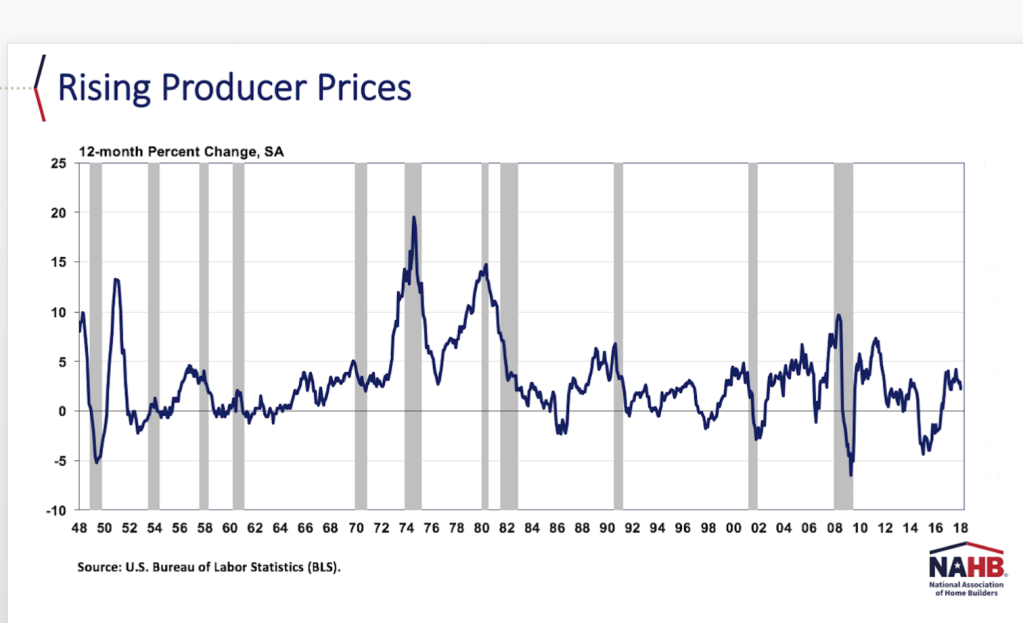

It is not just the direct effects of tariffs and other taxes that matter. As the chart here notes, producer prices tend to accelerate late in an economic growth cycle. Higher producer prices, like rising interest rates, slow the economy and introduce recession risk. Thus, policymakers should undertake efforts to manage or even reduce costs for business late in the business cycle. Regulatory costs and more efficient tax policy meet this test. Unfortunately, tariffs accomplish the opposite.