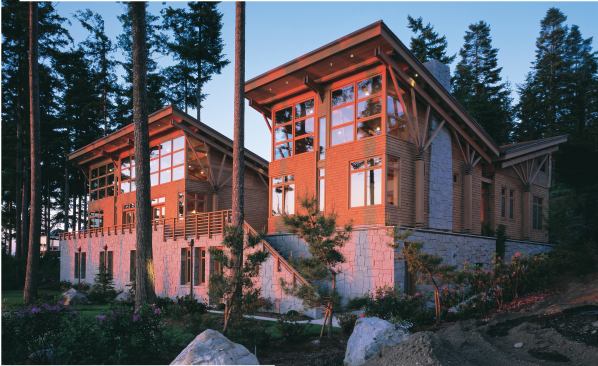

The soaring second floor of the house, clad in semi-transparent …

Far in the northwest corner of Washington state, about as close to Canada as you can get without crossing the border, sits the perfect house for an airplane buff. It perches on the edge of Semiahmoo Bay, which is part of Puget Sound, like a plane that’s just touched down. Its inverted roof spreads across the site like a pair of wings, opening gracefully to the bay and views of the Strait of Georgia.

Fittingly, owner Bob Davis spent 40 years designing and building planes as an engineer at Boeing. He and his wife, Clari, had finished raising their children, and they wanted a place where the two of them could reside for the rest of their lives. They envisioned a house with most of the main rooms on one level and plenty of windows to counteract the gray Pacific Northwest weather.

They tapped Seattle architect Nils Finne, whose blend of Modern-leaning style and reverence for natural materials is strongly influenced by Scandinavian design. Finne’s collaborator, builder Stan Starr, happens to have his own passion for planes—he’s an amateur pilot. He and his partner at Emerald Builders, Bill Miers, pride themselves on their ability to execute jobs with a high degree of difficulty. “If you can design it, we can build it,” Starr says.

Details: Fine Furniture

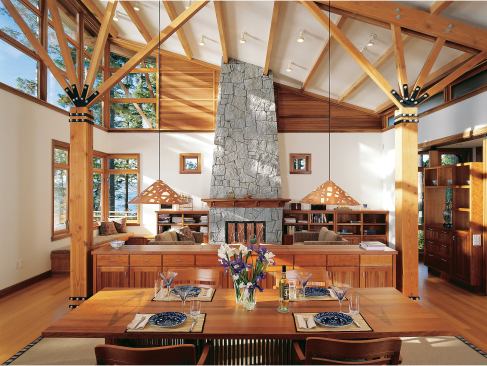

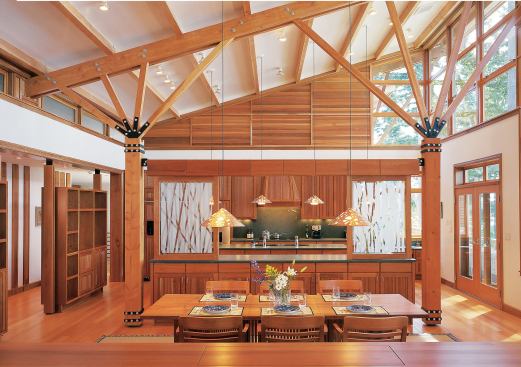

If the furniture in the Davis residence seems to mesh particularly well with the architecture, it’s because FINNE Architects designed them both. Nils Finne and project co-architect Scott Huebner designed the dining room table, master bed, coffee table, end tables, light fixtures, and a fireplace screen, taking advantage of a rare opportunity to extend their talents to furnishings. For the bed’s cherry headboard and baseboard they abstracted the imagery of the home’s fan trusses into a hypnotizing, branchlike pattern. The same pattern appears on the copper kitchen and dining room light covers, the copper fireplace screen, and the etched glass panels that slide to separate the dining room and kitchen. In some cases, the pattern was actually cut by a computer-aided laser that traced Finne and Huebner’s drawings onto the finish material.

Pieces of steel slice through the cherry coffee and end tables, providing a contrast that highlights the properties of both the metal and the wood. The dining room table is the show-stopper, though. Its inlay of Richlite, a black, synthetic material that resembles ebony, forms two diamonds that echo the V-shape of the table legs. More strips of the same material delineate the sliding panels under the tabletop that contain an extra leaf. The table encapsulates the fine craftsmanship and embrace of natural materials that permeate every square inch of the house.

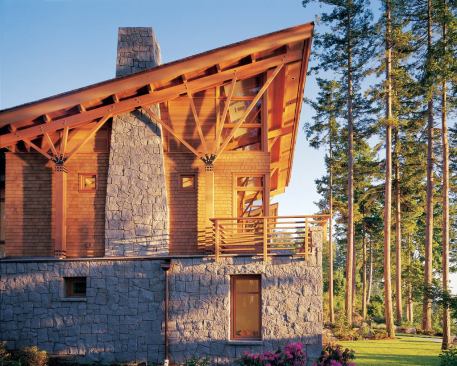

Finne’s design put that claim to the test. The house is located in a subdivision on a half-acre lot. In order to comply with mandatory setbacks, the Davises’ program, and the constrictions of the sloping site, he designed the second floor of the house, the main floor, to be slightly smaller than the first. The first floor starts at the front of the house as a foot-high granite plinth that gradually increases to 10 feet at the back. It serves as a table of sorts, with the second, cedar-clad story resting on top of it. Two rows of fan trusses march across the house, supporting the roof. An 8-foot-high band of clerestory windows wraps around the rear second floor, feeding light deep into the home’s interior.

Because of the different floor plates, the trusses, and all the glass, Finne’s plan had to be very carefully engineered. One false move by Starr, and the entire frame could be thrown off. The living and dining room trusses, for example, were set on steel-supported fir columns interspersed with cabinetry custom designed by Finne. It took two boom trucks to lower the trusses into place, one to turn them over, and one to insert them into the frame. “Those steel posts had to line up with the cabinets,” says Starr. “If they were off by even a little, the whole cabinet system would look wrong.” The same went for the foundation, frame, and windows—the plan’s rigorous, linear nature left an unusually small margin for error.

But neither Starr nor the Davises doubt that Finne did the right thing. Light pours into the cherry-trimmed main level, thanks to the clerestories accommodated by the inverted roof. The fir posts and trusses define different areas within the large central living space, eliminating the need for light-blocking walls. They also combine with the red oak floors and cherry cabinetry to create a warm, cozy atmosphere—no easy feat where lots of glass and 18-foot ceilings are involved. Finne feels that natural materials like wood and stone help make Modern design more approachable. “When we’d talk about the house with the Davises, we kept coming back to the emotional value of the materials,” he says. “The stone has a heavy, weighted quality; it grounds the house both physically and emotionally. The Davises were slightly nervous about going Modern, but I think the way we were talking about materials reassured them.”

The Builder: Listening Up

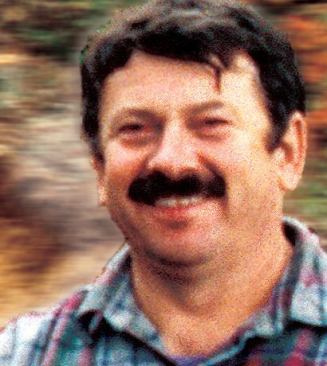

Stan Starr didn’t start out as a builder. He worked as a student personnel administrator at Eastern Wyoming University for one semester, until the job’s mental stresses took their toll on his health. “I was having back pain from holding all the tension in,” he says. “I wanted to be moving around, not listening to people’s problems all day.” Ironically enough, his listening and problem-solving abilities were exactly the qualities that made him the ideal builder for the Davis job. Architect Nils Finne designed the house right down to the precisely laid-out pinwheel tile pattern in the bathrooms. He even plotted the living room bookshelves so that carefully placed hallway artwork could be seen through the vertical spaces between the shelves. Such an ultra-designed project meant Starr had to be in constant communication with Finne and project co-architect Tim Myhr in order to carry out each detail just as it had been imagined. When the wood-clad hardware for a pocket door track in the master bath proved too bulky to allow room for a planned clerestory above the door, he disassembled it, stripped off the wood, and reconfigured the remaining steel pieces. The clerestory fit, and the track works smoothly. No matter how hard he tries, it seems that Starr just can’t stop trouble-shooting.

Another assurance the clients wanted was the knowledge that they’d always be able to get around their house easily. Finne complied by making every doorway 3 feet across, wide enough for a wheelchair. The master bedroom and laundry room are on the same floor as the main living area, which encompasses the kitchen, living, and dining rooms; the master wing connects to the public spaces through a glass-backed entry hall. The Davises and their visitors can access the three downstairs guest bedrooms via an elevator installed discreetly next to the front door. A wheelchair ramp leads from the garage into the entry hall. “We don’t need any of it now, but it’s nice to know it’s there if we ever do,” Clari Davis says. Radiant-floor heating, in addition to suiting the home’s high-ceilinged spaces, helps her asthma since it doesn’t blow dust around like forced-air heat does.

Any time a skilled architect and an up-for-anything builder work together they end up producing a showcase of details. The Davis house is full of them—the fine ribbing on all interior doors, cabinets, and molding; the copper light fixtures and fireplace screen; and the intricate, wood-and-metal open-riser staircase. Thick cherry mantelpieces provide suitably sturdy counterparts to the two granite chimneys. And the bathroom floors incorporate a methodically planned configuration of Brazilian slate, Chinese slate, and glass tile.

Exterior detailing also consists of copper, chosen for the rich patina it acquires with exposure to the elements. In fact, all of the exterior materials, such as cedar shingles finished with a semi-transparent stain, granite quarried from nearby Fox Island, and custom concrete pavers, stand up quite well to wind and water. “For me, time is an enriching agent,” Finne says. “I think a house should work with it rather than against it. You can’t get away from the natural environment, and if you try, it will find you.” The house will age comfortably, just as its occupants will.

Project Credits: Builder: Emerald Builders, Bellingham, Wash.; Architect: FINNE Architects, Seattle; Structural engineer: Monte Clark Engineers, Issaquah, Wash.; Geotechnical engineer: GeoEngineers, Seattle; Energy consultant: Ecotope, Seattle; Landscape designer: Star Nursery Landscaping, Seattle; Living space: 6,500 square feet; Site size: .5 acre; Construction cost: Withheld; Photographer: Art Grice (except where noted).

Resources: Bathroom fittings/fixtures: Grohe, Circle 400, Hansgrohe, Circle 401, Kohler, Circle 402; Bathroom glass tiles: Ann Sacks, Circle 403; Bathroom slate tiles: Pamas Tile, Circle 404; Kitchen fittings/fixtures: Kindred, Circle 405 and KWC, Circle 406; Lighting fixtures: Paulsen, Circle 407 and Resolute, Circle 408; Paint: Benjamin Moore, Circle 409; Stain: Cabot, Circle 410; Windows: Quantum, Circle 411.