Yesterday, we wrote about housing affordability. It’s without question the most important word in the business community. Its meanings are complex. Its significance, central to almost everybody who works in the housing community, stretches well beyond the bounds of the sector in to the very fiber of society and what we value fundamentally.

Actually, we could write about housing affordability every day and not cover all there is to know and do about it.

Two comments to yesterday’s story struck me as worth revisiting, and not with a glib reply in the comments box.

One, from “AmeriSus,” an appreciated frequent contributor of color and insight on our analysis, addresses a very important factor of what we count and don’t count in discussions of housing affordability. In the other critique, Ralph Bennett questions the very norms to which builders, investors, developers, and their partners hold themselves accountable when it comes to this sense of duty around affordable, decent housing for Americans.

AmeriSus observes that yesterday’s focus on the topic of how elastic new home prices might be based on looking at historic household data sets omitted a key consideration. Property taxes, as an unavoidable component of what each homeowner household pays each month, need to be included as part of the monthly payment calculus if there’s to be true insight around price elasticity, historic norms, and current home price and interest rate trends.

We’d agree. Municipalities, school districts, counties, states, and other tax districts almost everywhere place disproportionate burden on homeowners of new homes to carry the cost load. Layers and layers of taxes, fees, regulations and obligations, policies, covenants, etc., in many cases, filter who can and who can’t think of living in those places. AmeriSus correctly notes:

“In the northeast many states like New Jersey, as just one example, have seen property taxes on the exampled 1,800 sq. ft. home rise to now be in excess of $1,500 per month (more than, and in addition to all the costs discussed).”

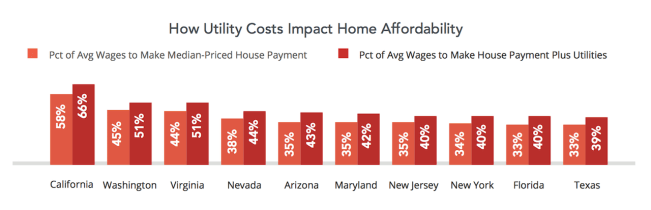

We’d add to this argument that any reasonable analysis of affordability–the real-life monthly payment power of a household with a decent-paying source of income–needs also to include the home’s energy bill. ATTOM Data Solutions takes up this issue in a recent analysis, “Utilities Add 25 Percent to Homeownership Costs,” whose introductory thesis is that those who buy median priced homes in 2017 will need to spend more of their household income than Americans have historically.

A new analysis conducted by ATTOM Data Solutions and UtilityScore for this report found that average wage earners will need to spend more than one-third of their income (33.5 percent) buying a median-priced home in 2017 on average across 931 U.S. counties analyzed.

Utility costs make housing even more expensive.

The median utility costs (electricity, natural gas, water, sewer) across the aforementioned 931 counties is $238 per month, according to data from UtilityScore. That adds up to an additional 7.0 percent of an average wage earner’s income on average across those counties (see Page 5 for more details).

Put another way, the median monthly cost of utilities adds an average 25 percent to monthly housing costs for a median-priced home across nearly 13,000 U.S. zip codes analyzed by ATTOM and UtilityScore.

This leads, in its way, to the second comment to yesterday’s thought piece, from Ralph Bennett, who finds it objectionable to consider that the market may tolerate median home prices where more than 40% of a household’s gross wage goes toward monthly housing payments. Bennett writes:

“In HUD terms this is a housing burdened household, when affordability is defined as 30% of gross income. Low inventory clearly indicates the availability of buyers at higher income levels for sure, and possibly for ‘non-supervisory or production’ workers, but my suspicion is that the numbers comfort those who believe we are providing affordable ownership to historic proportions of the population. And low supply of for sale housing means price rises and more families staying renters which is another problem altogether.”

Mr. Bennett’s thoughts here raise a flag we consider to be worth our attention. The question he appears to be asking is “do prevailing supply and demand business and market trends define acceptable levels of affordability in housing data? Or rather, should affordability be looked at through other lenses, with framing that includes more of the real-world population that isn’t currently participating in supply and demand equations?”

Both AmeriSus and Bennett’s questions and observations enrich the conversation, and we welcome more of the same. They remind us that this term, affordability, may be one of the most overused under-understood terms in housing, and one that has both moral, societal freight as well as business opportunity and challenge in its extensive scope of meaning.