Maxwell MacKenzie

Exterior work for the restoration of this 1893 mansion included …

Standing in the heart of the historic Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C., the house that would become Mother & Child was a building of some distinction from the time it was new. “It was built in 1893,” says architect Ralph Cunningham. “It’s one of the rare Colonial Revival houses in Georgetown.” By the 1960s, though, that didn’t count for much. In 1961, the owners of the neighboring Evermay estate, one of the city’s largest, converted the building for use as a guesthouse, stripping much of its historic character in the process. “Preservation was just in its infancy,” Cunningham explains, “so they felt free to butcher away.” Some 50 years later, in a very different regulatory environment, Cunningham and Crofton, Md.–based Horizon Builders executed a heroic do-over that gave the house a new lease on life as an urban family home as contemporary in function as it is historic in character.

Project Credits

Water Works

The success of this project owes much to landscape

architect Richard Arentz’s garden plan, and the plan’s centerpiece is

the fountain that animates the rear patio. “It’s a play fountain,” says

Arentz’s associate Michael Rossetti, who explains that it uses the same

components as public fountains designed for children to splash in.

Thirteen water jets are set flush with the stone patio, leaving an

uninterrupted walking surface. Each jet incorporates an LED light and a

drain that recirculates water to a cistern buried in the garden. A

computerized system housed in a vault beneath the fountain controls an

infinitely variable water-and-light show. “You can set what jets are on;

you can set the height of each jet,” Rossetti says. “The programming is

limitless.”

Step One: Negotiate the regulatory maze. With the help of Washington-based architectural historian Emily Eig, Cunningham learned that the house actually had undergone two significant renovations. The first, before 1920, added several feet to the rear of the building to accommodate indoor plumbing. The 1961 project went much further, removing the front porch and rooftop widow’s walk, relocating the center-hall entry to the side of the building, and scrambling the classical symmetry of the original floor plan.

Facing the formidable Commission of Fine Arts, which holds sway over design matters in the Georgetown Historic District, Cunningham offered a proposal: A full restoration of the original 1893 building in exchange for permission to build a sympathetic—but somewhat more contemporary—rear addition. “For Georgetown, it was a fairly radical thing,” says the architect, who nevertheless won approval. “It wasn’t a fight. It was really like a long dialogue, which I really give them credit for. They could have had their heels dug in, and they didn’t.”

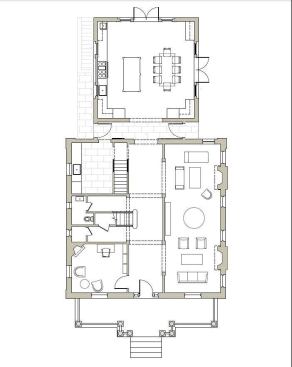

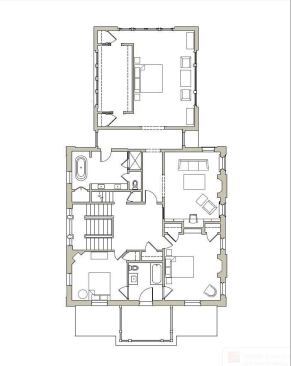

Step Two: Establish a clear distinction between the building’s restored and new components. Cunningham’s scheme plays off the simple massing of the original house—the “Mother,” essentially a brick cube with a hip roof on top—by adding a smaller cube, the “Child,” at the rear. “The Mother is 35 feet in every dimension; the Child is 24 feet in every dimension,” says Cunningham, who connected the two via an inset “hyphen” that lets each read as a separate geometrical solid.

Cunningham worked closely with landscape architect Richard Arentz to integrate the building with its walled rear garden, which screens out neighboring properties at both sides, but opens at the rear to borrow views of Evermay’s elaborately landscaped grounds. Cunningham’s overriding aim was to make the addition subordinate to the original house, “like a pavilion in the garden.”

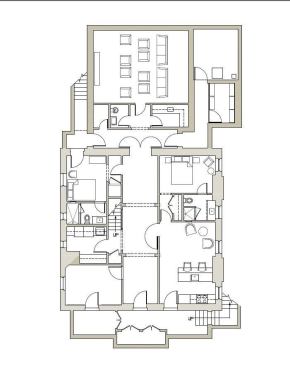

Inside, Cunningham restored the main house’s original center-hall layout, amplifying its impact by extending the strong central axis through the new kitchen and out into the garden. Having restored the old rooms’ gracious proportions, Cunningham and Washington-based interior designer Tom Pheasant were forced to improvise period-appropriate trim and finishes because so little of the original interior remained. “Pretty much the only thing that was intact was the stair and the second-floor hall associated with it,” says Cunningham, who penned bold neoclassical casework and moldings for the original areas of the house. A leaner, more abstracted trim schedule inclines the new spaces—the kitchen, a master suite above, and basement-level theater and guest quarters—in a more contemporary direction.

Step Three: Find a uniquely skilled builder. The building’s historic value and tight urban site demanded a contractor with expertise in urban historic preservation. General contractor Horizon Builders specializes in surgical-strike interventions in dense residential neighborhoods. “On some of these jobs we put in $6,000 to $10,000 just to cover the parking tickets,” says company principal George Fritz. The crew saved and cleaned bricks removed during demolition to make seamless patches in the remaining walls and restored century-old double-hung windows to maintain the integrity of the street façades. “We had to jump through all the usual historic hoops,” Fritz says. The narrow lot made modern aspects of the job equally challenging. “We underpinned the whole house and dropped the basement floor 2 feet,” he says, in addition to drilling wells for the geothermal heat pump system.

But the results show nary a sign of strain. Viewed from the sidewalk, the project neatly turns the calendar back to 1893, and the addition builds on the experience of the original. “It’s very sympathetic with what’s there,” Fritz says. “It feels good; it fits well. And when you’re in that kitchen, you’d never know you were in the heart of D.C.”