With its abstract geometry and museum-quality exterior materials…

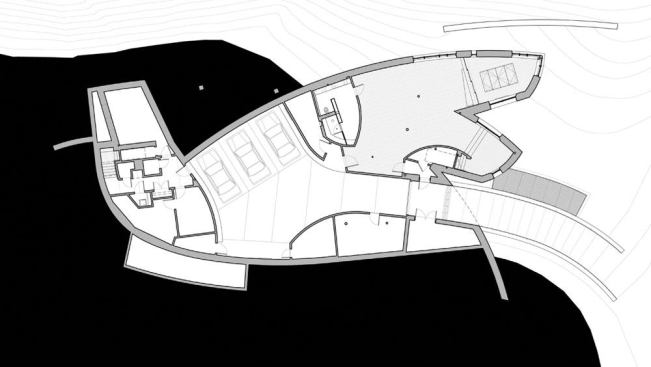

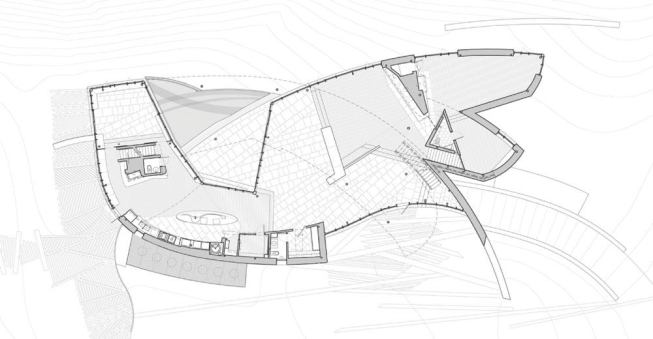

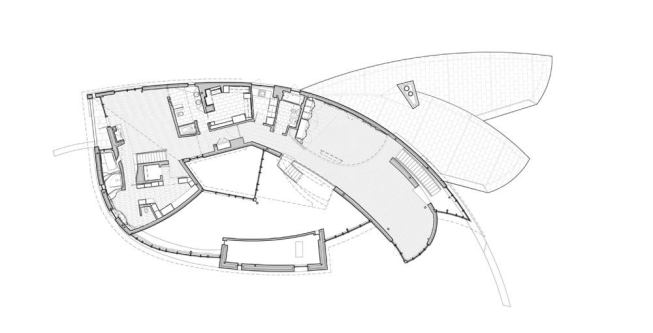

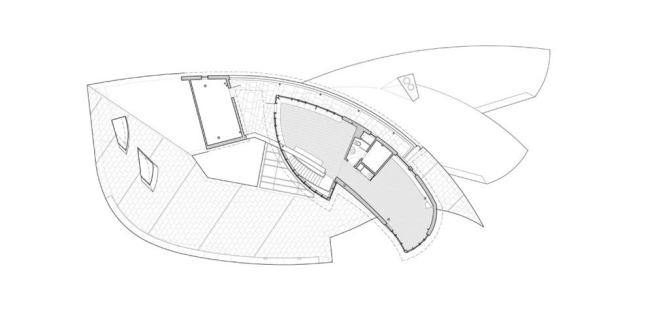

Consider the relationship between the first- and second-floor plans. Not only does the perimeter wall of the second floor overlay only a small section of first-floor wall, its structure rests entirely on steel columns. If one were to remove every exterior wall at the first floor, the second and third floors would remain undisturbed. Despite its structural independence, however, the volume that contains the upper floors asserts itself powerfully in the first-floor space. From its glazed prow, which cantilevers over the front door, it curves into the first-floor volume, sweeps through the living and dining areas, moves outdoors over the courtyard, then joins the main mass of the building to cap the screen porch and breakfast area. The element’s purple-and-green slate exterior siding and convex “belly” remain consistent throughout, lending it the imperturbable presence of a great whale. The belly’s plaster surface is covered in aluminum leaf, applied in a pattern whose subtle irregularities reinforce the form’s organic quality.

Project Credits and Resources

Project credits:

Builder: Thoughtforms Corp., West Acton, Mass.; Architect: Schwartz/Silver Architects, Boston; Staircase fabricator: TriPyramid Structures, Westford, Mass.; Living space: Withheld; Site: Withheld; Construction cost: Withheld; Photographer: Alan Karchmer, with photo stylist Sandra Benedum, except where noted.

Resources:

Bathroom fittings and fixtures: Boffi USA, Dornbracht Americas; Bathroom and kitchen cabinets, interior paneling: TFC Studios; Dishwasher: Miele; Entry and patio doors, skylights/roof windows: EFCO Corp.; Fireplace: Moberg Fireplaces; Flooring (rubber): Mondo America; Garage doors: Cliff Compton Inc.; Garbage disposer: KitchenAid; Hardware: The Nanz Co.; HVAC equipment: Buderus, Lennox International, Viega North America; Insulation: Icynene; Interior doors: Herrick & White; Kitchen fittings and fixtures: Dornbracht Americas; Lighting fixtures: Lightolier; Oven: Gaggenau USA/Canada; Paints/stains/wall finishes: Benjamin Moore & Co.; Range: Wolf Appliance; Refrigerator: Sub-Zero; Trimwork: Herrick & White, TFC Studios; Windows: Amherst Woodworking, EFCO Corp.

Beneath the belly, an L-shaped room divider made up of massive bluestone slabs delineates a sunken living room that focuses on a fireplace wall of highly modeled, acid-etched steel plate. In the first floor’s expansive living space, Schwartz explains, “we felt it was very important to introduce elements of intermediate scale, which are like little buildings, so you can measure height and distance.” The kitchen’s cabinet wall describes a curved and tilted plane that recalls Richard Serra’s steel-plate sculptures. The shape is echoed in the concrete kitchen island, an elliptical counter resting on a base whose boatlike shape inspired its nickname: “The Sloop.” Produced in a monolithic pour under controlled conditions at the concrete subcontractor’s shop, the base was trucked to the site and set as a finished piece. “In the process of construction, this alone took about a year,” Gustin says of the island. “It was an adventure.”

The house is full of adventures, both technical and visual. Its two stainless steel-and-structural glass staircases are the work of TriPyramid Structures, the Westford, Mass.-based fabricator whose high-tech fittings support the famous glass stairs in Apple stores around the world. A local boat builder adept in composite construction produced a wall of gleaming black carbon fiber shelves for the first-floor office. On a project that incorporates so many pieces that approach the level of fine art, Gustin observes, “Your vendor base, which was really small to begin with, just gets smaller.” For any single item, “there may be one or two people who can do that.” The project also drew on Thoughtforms’ considerable roster of in-house talent. “We used multiple vendors for the millwork,” Gustin says, “but our guys did most of the really difficult stuff.”

The Builder: Room at the Top

Founded in 1972, Thoughtforms Corp. assumed its current form in the

1980s, just as the super-high-end custom home market began a surge of

unprecedented growth. Partners Andrew Goldstein (shown) and Charles

Barry tailored the company to serve that market, gathering the expertise

to handle some of the most demanding residential projects ever

conceived. But that was before “The Great Recession.” How is the company

faring now, as custom builders lay off idled staff and fall back on

remodeling projects to keep the lights on? Will Goldstein and Barry have

to hitch this racehorse to a plow?

Not just yet, it seems. “It

would be unrealistic to say things aren’t changing,” says Goldstein, who

estimates his company’s volume has shrunk 10 percent to 20 percent from

its peak. “But we know projects like this—and even bigger, more

expensive ones—are still around. There are several projects now [in

planning or under construction] that are the largest, most custom ever

done in this area, and we’re lucky enough to have a couple of them.”

With

work currently booked and in negotiation, Goldstein reports, “We are in

a really good place, and we’re potentially in a great place. The future

is still a little scary, but in a couple of years it looks like we

should be back to where we were a couple of years ago.” If so, the

company can draw some reassurance from the experience: “Even in this

recession, surprisingly, there still are a fair number of people who are

interested in building either a very lavish house or a very artistic

house.”

Gustin’s charge throughout was to make the sum of these efforts function seamlessly as both dwelling and sculpture. And, by the way, you don’t slap a downspout on a sculpture. “All the drainage is internal to the house,” he says. As a routine matter, the project called for “commercial applications with residential tolerances.” But at its most demanding, it put the builders on a frontier of sorts, pioneering details never before attempted: a master bath built up in geological strata; a modified rainscreen system that combines watertight caulk joints at the slate siding panels with the backup of a continuous drainage plane; and the courtyard’s stainless steel infinity-edge koi pond.

So if the planning board failed to fully comprehend this house, it comes as no surprise. Even the architect admits he went out on a limb with much of what he designed. Schwartz recommended Thoughtforms for the job because, he explains, “I didn’t think anyone else could do it.” This may well be a once-in-a-career project, he says. But if another one like it were to come along, Thoughtforms would have to be the contractor. “They invented ways to build things I didn’t even think you could build.”