We’ve seen it before.

The onset of a crisis–this one 13 or 14 years ago–pulled demand forward. Furiously. Before the market fell off a cliff in 2005, new home sales volume soared. The narrative then–until it wasn’t–was that structural demand, economic strength, and corporate profits and capital investment trends would continue supporting momentum.

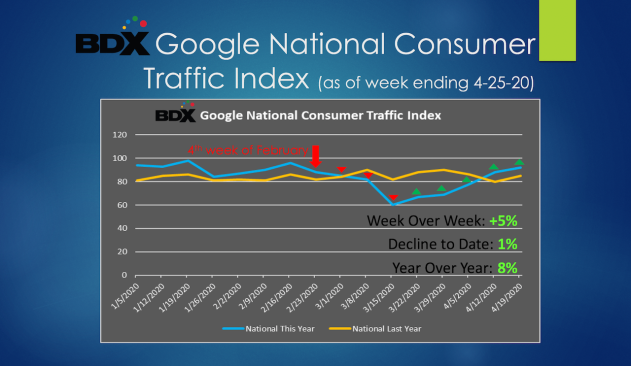

In today’s market, we see home buyer search trends tracking upward.

We hear of master-planned communities, like Balmoral in the Houston-area town of Humble, Tx., racking up record-breaking absorption rates in the past couple of weeks, in the face of the double-whammy of oil economy collapse and COVID-19 impacts.

At the same time, commentary from executives of a number of public companies in first-quarter earnings calls, in almost eerie unison, cites “improving conditions” from late March into mid-April. To listen to these executives, it sounds as though they’re viewing disruptions as “transitory” and contained. This view renders a haunting deja vu to many of their quotes and comments well into the beginning of the housing collapse in the mid-2000s.

Now, it’s hard to argue with consumer behavior, but what if–as in mid-2005 or so–consumer behavior did not know what it did not know, yet?

All this, as every measure of the fundamental economy weakens and shows continued, historically-rapid deterioration. All this, as the Fed, and Congress, and the White House promise no end of emergency policy support, for people, for businesses, for society.

The promises are for a bridge over an abyss whose depth, whose duration, whose essential nature is yet unclear.

The pivot from a housing market that was accelerating fast into the New Year, to one that slammed into pandemic pandemonium in early March, to one that we’re trying to take stock of in the early-going after the shocks, leaves us just one way to express the current state:

Surreal.

Another week goes by, and another body-blow to the most basic ingredient of household wherewithal–jobs and income–registers here.

Now the big questions are not just about “duration” of the economic disruption, but about whether catastrophic job and income loss is either temporary or permanent. Unprecedented Federal emergency support has poured dollars everywhere as far as the eye can see into support during the convulsions. The Fed’s aim is at “avoidable insolvency,” but what about unavoidable insolvency? The underlying premise of all that we attribute value to is a “living wage.” All of these emergency dollars assume people who’re disconnected from that living wage will reconnect. Soon.

Believers in a V-shaped recovery obviously think furloughs and business shutdowns will reverse–like the lights switching back on after local and state officials lift lockdown orders. Those who picture a U-shape, envision a two-quarter work-out before deterioration shifts to a reconstructive economic pivot. Then there are the L’s, the W’s, and whatever other alphabetical images we can imagine to characterize what we now face.

The endgame here is the “stronger economy” we reach when we come out of the excruciating pain of the present.

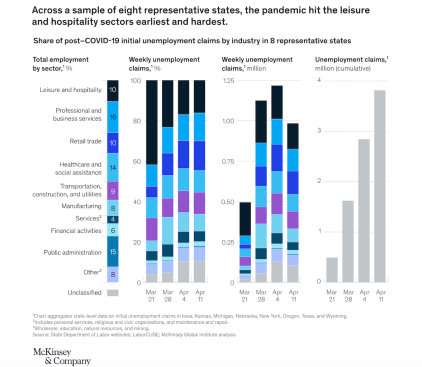

This McKinsey analysis, which looks not just at quantifying job losses, but livelihood “vulnerability,” maps challenges–near-term and structural–for employment and household incomes that the novel coronavirus pandemic and the concurrent economic disruption have drawn into sharp relief.

“Demand shocks have been reverberating through all sectors. Now that pandemic-related unemployment claims have been pouring in for several weeks, the losses associated with the initial shutdown are cascading into knock-on effects. While leisure and hospitality accounted for most of the earliest layoffs and furloughs, the share from industries such as retail trade, manufacturing, nonessential healthcare, and professional services has been growing. We estimate that up to 57 million US jobs are now vulnerable, including more and more white-collar positions. By way of context, some 59 million jobs are at risk in the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland, which have a considerably larger population.

“We find significant overlap between the workers who are vulnerable in the current downturn and those who hold jobs susceptible to automation in the future. In addition to the effects of technology, the crisis itself may create lasting changes in consumer behavior and health protocols. To put vulnerable workers on more promising and sustainable paths, the US response should incorporate a longer-term view about the resulting occupational shifts and the development of skills.

The McKinsey analysis notes that jobs recovery takes longer each time after a recession. This flies in the face of many economists’ assertions that income losses due to the COVID-19 outbreak are temporary and will be patched over by the $2.6 trillion in legislated emergency funding programs.

Yet, builders’ talk-track–at least at the national builder level–is that conversion rates among new home searchers show that tougher conditions have flushed out tire-kickers and left a solid remainder of buyers. Among the most well-respected analysts and housing observers currently view the hit to new home sales as a worst-case 20%, year-on-year decline.

That figure stands out in my mind as the predominant worst-case scenario most of the big builders predicted as the housing economy collapsed in 2006, 2007, and 2008. Many of these builders forecast that worst-case scenario even as the market-as-they’d-known-it was coming undone.

This household income “vulnerability” that McKinsey points up signals, in my mind, a more structural, longer-running challenge for builders, and a moment of higher risk than many of them are currently accounting for.

What we know is this. Public companies, big companies, geographically-hedged companies, companies with a diverse and seamless product and customer segment mix, companies with clout among suppliers and manufacturers–the very few organizations like this–will do better.

Home building companies whose capital comes from bank and private equity lenders, friends and family investors, and their own personal money and guaranties are feeling the heat. They’re the ones whose viability as going concerns rests on their ability to keep delivering cash back into their tills to replenish what they’ve already spent.

They’re stuck in this surreal moment. In a big float. Counting on pulling in their backlogs, and finding every which way to “take chips off the table” to reduce their debt exposure where they can.

All the policy and emergency rescue programs to date have 30-, 60-, 90-day horizons, for the most part, and many of them leave a holes and disconnects in the money flow that squeeze businesses who’ve borrowed based on a prior outlook of a strong and growing demand for new homes in all the months of 2020 and beyond.

Mortgage forbearance may help keep “shadow inventory” of distressed homes to a minimum. However, these rescue measures, and even low, low, low interest rates will not generate income for down payments, monthly payments, etc. necessary for a healthy pipeline of new orders, especially as materials and local fees and costs pressures are expected to rise.

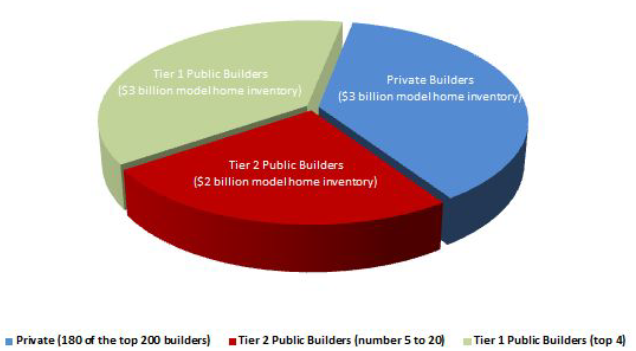

Privately capitalized home builders, and even some publics, have turned increasingly to model home leasebacks, as both “an insurance measure and as a cash generator,” according to Ed Steffelin, a senior vp at George Smith Partners and co-founder of real estate investor STAC Capital Management.

Steffelin describes the model leaseback value proposition this way:

“We appraise the [builder’s model] homes,” says Steffelin. He adds, “STAC purchases the homes at a discount to appraisal. Typically this would be done as a portfolio to start and then the builder can add or substitute into the pool over time. The size of the discount depends on the portfolio size and type, builder profile, and if the builder receives any upside participation at the sale of the home. At closing of the home by STAC, a triple net lease is entered into between STAC and the builder at a rate that depends on many factors. Each home in the pool will have a set lease term of between 1 year to 3.5 years. During that time the builder pays taxes, HOA and insurance much like they would if they continued to own them. During the lease term, if the homes are sold the lease may terminate early. If the home is not sold during the lease term and the lease runs out, then the builder converts the home back to a traditional home (converting any sales garages or eradicating any additional parking at the home) and STAC would own it with no further obligations from the builder. We do have structures where the builder can participate in the profit when the home is sold and/or receive commissions for selling the homes. There are accounting considerations around these but that comes down to a builder’s motivation.”

Source: Industry estimates, based on one model per 60 units sold.

STAC estimates that public and private builders have one model per 60 homes as the models last for around 3 years on average, and that the model home universe, including top tier public builders, second-tier publics, and private home builders is roughly $8 billion.

“It’s a way to de-risk the balance sheet on one hand, and generate cash flow on the other.”

When demand is in the vacuum of doubt and uncertainty we’ve now entered, tactics like this one are make a lot of sense, especially for builders shaking the bushes for cash to weather the continuing storm.