renaissance man In addition to a thriving practice, Welch has always cultivated an artistic life around the edges of architecture. In 2000, following two articles he wrote about Philip Johnson for Texas Architect magazine, he authored the book Philip Johnson & Texas (University of Texas Press). “I was intrigued by his appeal to Texans,” Welch says of Johnson. “I finally determined it was his personality and enthusiasm that made people call him back—and his diplomacy and self-effacement, his not taking himself too seriously. The media never got that part of him.”

Welch’s fascination with light also led to a photography sideline and continuing exhibits at a handful of galleries in Dallas and Houston. It’s a talent he discovered during his year in Paris. Disappointed with the classes offered at the École des Beaux-Arts, the story goes, he lobbied his Fulbright adviser to let him document the city on film instead. “I thought, ‘I can’t undergo an education in this institution,’” he says. “It seemed so fusty and out of touch.” Leica in hand, Welch spent the next 12 months taking the subway to isolated parts of Paris and living the life of an impoverished artist.

Soon thereafter, the fateful dinner party occurred. Ford offered him a job that night, and Welch spent the next five years working in Ford’s Houston office. When Ford and Corpus Christi-based architect Richard S. Colley won a design commission for the landmark Texas Instruments Semiconductor Building, Welch was sent to Richardson, Texas, to oversee its construction. By 1959, with Ford’s blessing, he moved to Midland, Texas, to accept his first solo commission; he established a practice there before settling in Dallas in 1985.

Dallas architect Max Levy, FAIA, who has known Welch for 20 years, says that while most modern designs are dashing and self-concerned, Welch’s floor plans and details are very polite. “They’re never just all about themselves,” he says. “They don’t just turn creative somersaults for the architecture audience; [they] accommodate life in a very courtly and genteel way. People who don’t have a great affection for Modernism still respond warmly to his work. That’s very rare, but that is what he has accomplished.”

When asked to define how his work has evolved, Welch says that, if anything, it’s become more conservative. “I’ve won a lot of design awards, but these days they’re going to more cutting-edge stuff. I’m not comfortable doing that. It’s forcing something for me, but it’s easy for the younger generation.” Over the years he’s chosen to run a small office of four to eight employees, and his goals remain the same: “to get the next job,” working with his staff of three architects and an office administrator.

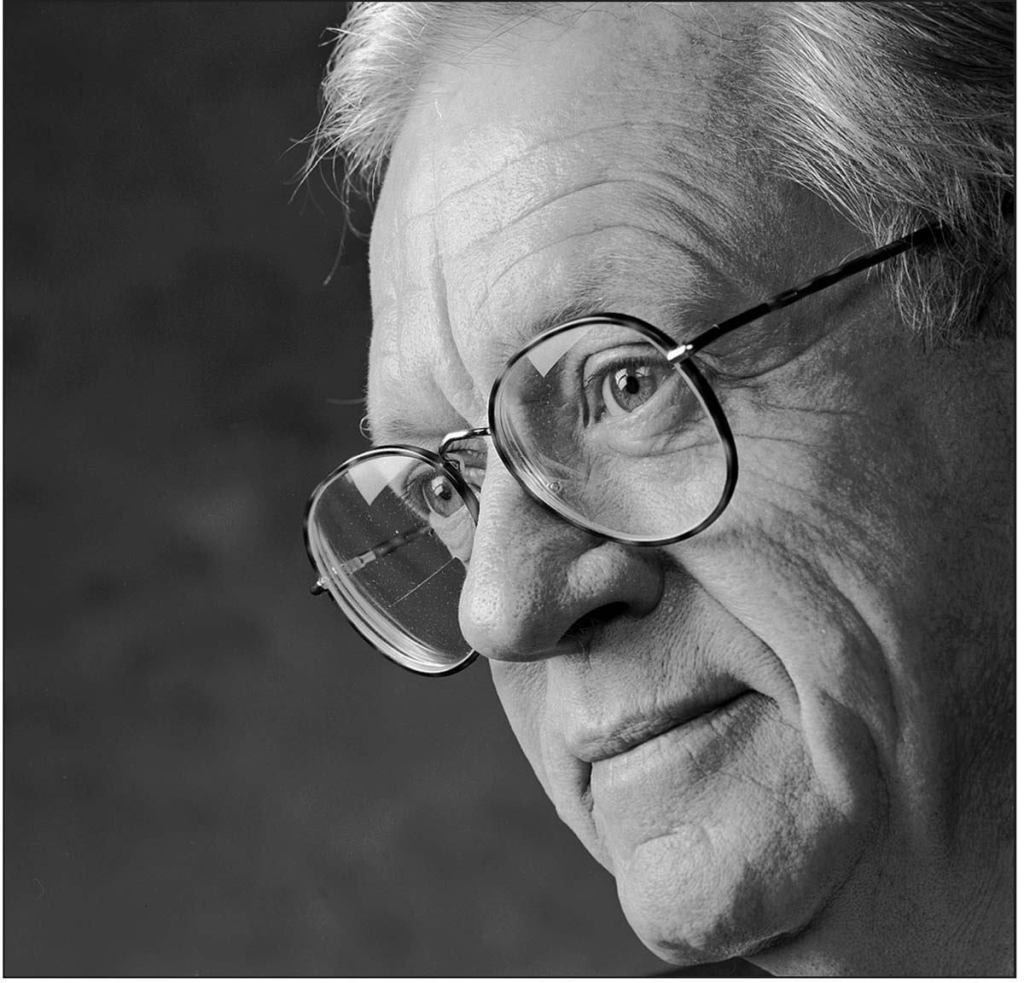

Like Ford and Johnson, whom he admired, Welch is blessed with an idiosyncratic charm. He possesses an inquiring mind, an ebullient personality, and a memory for good stories, and this particular combination of talents has won him a loyal, well-heeled clientele. It’s made him a mentor to a revolving door of young interns. And his wide-ranging enthusiasms—for writing, public speaking, and photography—have inspired his Texas peers.

Earlier this year, Levy penned a letter to the Texas Society of Architects supporting his nomination of Welch for the TSA Medal for Lifetime Achievement—an honor Welch accepted in early November. “The baton of regional modernism was passed to Frank Welch,” he wrote, “and he has advanced it far down the track, setting the pace for the rest of us.”