No single builder owns the Boston-area market in high-end custom homes, but every custom builder here knows the name Ken Vona. In business for 33 years, Kenneth Vona Construction has become nearly synonymous with a certain type of house: the best that money can buy. By the height of the mid-2000s building boom, other custom builders considered it a mark of distinction simply to bid against Vona. We checked in with Vona recently and learned why construction labor is in short supply, why he’s using an Ohio millwork shop for a job in New Hampshire, and why no one should launch a custom building business before age 28.

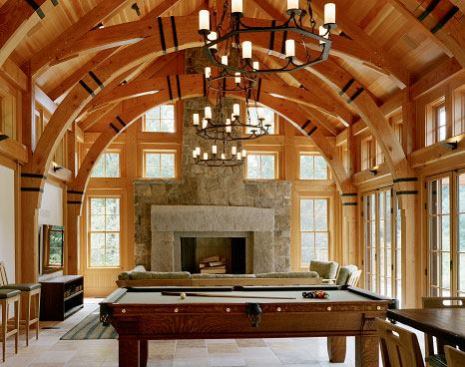

Sam Gray Photography

Vona’s stock in trade has long been premium projects like this…

How did you get started in the business?

Peter James Field/agencyrush.com

Ken Vona Owner Kenneth Vona Constructionwww.kenvona.comType of business: Custom building, remodeling, home maintenanceYears in business: 33Employees: 652012 starts: 3

My dad was a small contractor, doing kitchen and bathroom remodels. He used to drag my two brothers and me to the jobsite to help him. I swore I’d never do this for a living. But after two weeks in college, I felt like a caged animal. So I said to my parents, ‘I’m going to start a business of my own.’ The economy was really suffering at the time—it was 1980—and I was just a one-man show for several years. But things picked up, I hired some people, and today I have more than 65 employees. We’ve built about half a million square feet of construction in the past 10 years alone. We work in the $400-to-$600-a-square foot range, and we’re working on anywhere from 40,000 to 70,000 square feet of homes during any year.

How did you work your way into the high-end market?

We did some work for a couple who were moving up in their field—they were in banking—and they passed my card to even higher-ups in their company. The next thing you know, we went from installing doors to building additions to building 6,000-plus-square-foot homes. That period, starting in the 1990s, was an era of growth in homes that I don’t think we’ll ever see again. Today our typical project—a nice one—is a 10,000-square-foot, high-end custom home. But we built a home that was 44,000 square feet. And we also run a maintenance company, so we do projects as small as replacing a screen door.

How do you sell to today’s clients?

There’s still a clientele out there that wants high-end work, but everyone is looking for value right now. We’ve sharpened our pencil, the same way everyone else has. But we’re completely an open-book company. Everything is spelled out from the start of the job, so clients clearly understand where the money is going. We give them reports every month of every dollar we’ve spent. There’s an opportunity for them to be part of the process instead of just the person writing checks. Most educated people want quality because they know in the long term that will save them money. Explaining the process is what usually sells the job.

How have you dealt with the recession’s impact on your subcontractor base?

We lost six subcontractors that were important to us: two millwork companies, two concrete form companies, one plumbing company, and one painting company. They loved working for us, but out in the rest of the world they just lost money constantly, and they couldn’t stay in business. It’s been difficult because now the marketplace has swung in the opposite direction, and there aren’t enough quality, high-level vendors or subcontractors to handle the workload. We’ve had to go outside of Massachusetts to bring other vendors in. We’re actually using a large millwork company in Ohio to do a job for us at Lake Sunapee in New Hampshire. We’ve had to reach deeper into the marketplace to see who else survived the past four or five years and can handle the work.

What’s your advice to young builders starting out today?

The school of hard knocks is not the place to learn construction. If I were starting out today, I would get a construction management degree and then intern for four years—two years in the field and two in the office—before deciding to do it on my own. And along the way, I would minor in psychology—and I mean that. Before entering a contract for hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars, I think one needs to understand how the other person might be thinking about it. And nobody should be opening a construction company before the age of 28 because there’s just too much to learn. I also believe in hiring key people to do the things that I don’t do well. I couldn’t run this company without my two partners, Jim Koulopoulos and Brian Vona (who’s also my younger brother), our director of operations, our office manager, and the rest of our top-notch employees. It’s crucial to recognize that you don’t have certain skill sets and that you need somebody else to do those things. You can’t be great at everything.

How do you assemble and maintain a top-flight staff?

During the past four or five years, with the economy down and no construction jobs to be found, nobody’s entered the labor force. Finding people to do the work is very difficult, and I think it’s only going to get worse. We constantly run a “looking for qualified people” notice on our website, and, believe it or not, people find us through that. If we’re looking for somebody, that’s usually where we start. We believe in hiring the right person and training them, rather than hiring someone who already has set ways of doing things. And we believe in taking care of our employees, so turnover is minimal. We automatically contribute 3 percent to their 401(k) plans. That’s non-elective; we don’t require them to put anything in. 2012 wasn’t a great year for the company, but we still paid an additional 4 percent of our payroll in profit sharing. In the past nine years, we’ve paid 119 percent in profit sharing.

Unfortunately, there’s limited room for advancement within a construction company. We address that with bonuses and also by making people feel part of a team. At the tail end of a job, we send our managers and office staff out in the field, not only to clean the house or shovel snow, but also to see what they were part of. They weren’t just pushing paper. We brought together 10 million pieces of a puzzle and put it together in 16 months, and they were part of that.