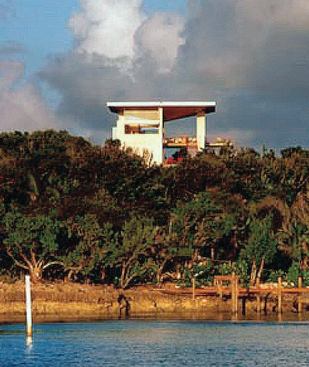

In his design for the Strickland- Ferris Residence, Frank Harmon…

When Harmon returned from London in 1970, he landed in New York and went to work for Richard Meier. During his three years there, he got married before returning to London to open an office with some of his old classmates. “We couldn’t have picked a worse time,” Harmon says of the British economy, which was in the midst of its worst slump since World War II. After trying for six years to build the business, Frank and Judy came back home to North Carolina. “We both loved architecture and the landscape and decided that we’d have a much better chance of working on those things in America.”

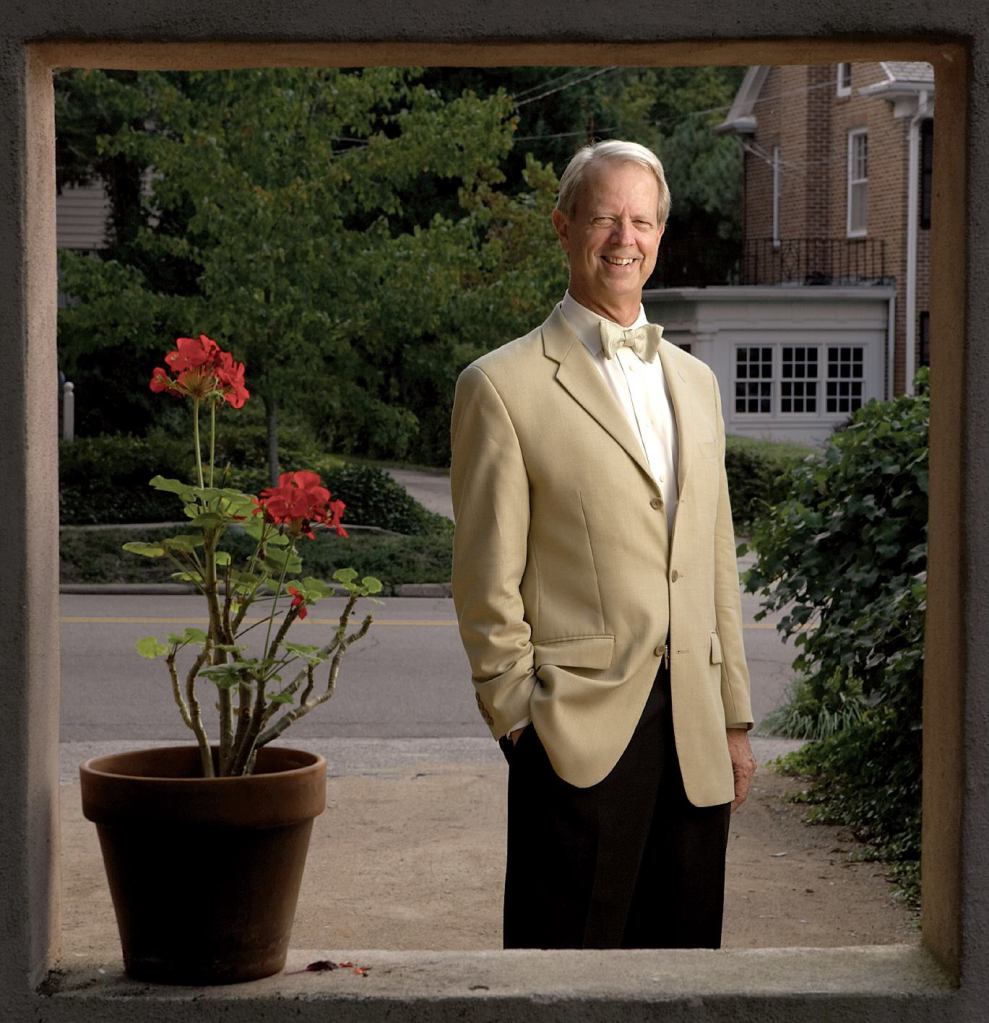

Harmon’s view of architecture was transformed when he began to teach at N.C. State—not so much because of the university, but by mere happenstance. “As a young faculty member, I was in the mailroom one day and this very gentlemanly figure came in wearing a Brooks Brothers suit and introduced himself. It was Harwell Harris. We immediately became friends. I don’t know why. We just had a magnetism.”

Harmon already knew a bit about Harwell Hamilton Harris, who had been the darling of the architectural press in the 1930s and 1940s. “I had discovered Harwell when I was young. I had seen this very fetching building that looked like it hovered over a hillside in California. It was one room and it had a rush-mat floor and four slender columns and a roof that looked like an upside-down boat. It turned out this was his Fellowship Park; it was where he lived.”

Over the next nine years, until Harris died, the two men were together often. During that time, Harmon got to know the man who learned his craft under Rudolph Schindler, developed a thriving practice in California, moved to Texas to head the architecture school at the University of Texas, and relocated to Raleigh during vibrant times at N.C. State.

“Harwell was a big influence on me in this way: He taught me that every client and every situation is different and new,” Harmon recalls. “And it is the architect’s job to understand the needs of every situation and every client. He loved to say that the house is a portrait of the client. He was a very important person to me—still is.”

tactile tactics Among the many ways Harris taught Harmon to experience architecture was through a sense of touch. “It was a revelation to me when I was young and used to study buildings in magazines. It was visual. But when I went to see things such as Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye, I was blown away by the fact that it had gorgeous ceramic tiles on the floor. And the walls were actually quite rough. It was something you wanted to touch.”

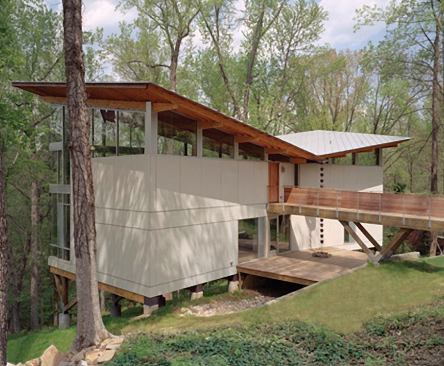

Harmon infuses his own buildings with many of the same qualities. On a formal level, his work—including the North Carolina Pottery Center and the woodworking studio for sculptor Stephen Wainwright—are so strongly based on precedents of unassuming agricultural buildings that critics are quick to label his work vernacular. But seen in isolation, Harmon’s designs for residences such as the Taylor House and the more recent Strickland-Ferris House are much more progressive in outlook—hard-edged, abstract, and pure in the details.

Harmon attributes that contrast to the nature of the clients. “With most of the larger projects, the client is a group of people. And working with a group is different from working with a single person. For example, the Pottery Center is in a region of North Carolina that is very old and, in many ways, conservative. A Bauhaus Modern building was not going to do for them. I would have gotten nowhere.”

On the other hand, by designing a building that recalled a barn or studio, Harmon was able to engage the clients. “What I would give that building was a sense of proportion and rhythm —and even elegance—that was of the 21st century. And it worked. They could relate to that.” It’s an approach that he attributes again to Harwell Harris. “What people thought was cold and threatening modernism, he made warm and approachable,” Harmon says.