Who can doubt, one of the heavier lifts in housing innovation is currently being borne by products and materials manufacturers who supply the builders? Materials whose functionality, aesthetics, strength, healthfulness, and ease of installation reflect quantum materials science leaps ahead are here, and the materials scientists behind them are only now just really getting started. We’ve had an opportunity to visit the innovation centers of a dozen or more home building products manufacturers over the years,

Graphene’s potential applications boggle the mind. Too, light-as-air aerogels, self-healing, bio-inspired plastics, and metamaterials that alter light, and a host of other new materials whose molecular make-up–capable of harvesting heat, capturing solar, conducting electricity, etc. These super materials resemble a new breed of talent–like today’s hyper-talented Olympians–for the job of making us safe and comfortable in our sheltered spaces.

Still, there’s the real world, on oh-so-human job sites, which serve as a humbling pause button to all these heady advances and imaginings. Lighter, stronger, healthier, more powerful, more sustainable, easier to install, sure … how about looking at the way things really look when you add that most imperfect element to these whiz-bang developments? People doing their jobs.

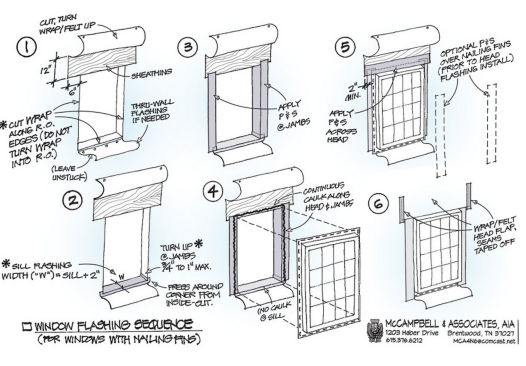

Take a look at what can and does happen on jobsites around the junction of three quite innovative building materials–flashing tape, housewrap, and windows–when it comes to flashing windows. In isolation, each of these materials or products has progressed lightyears ahead of their versions from a more un-evolved past. Journal of Light Construction contributor Harrison McCampbell, a forensic architect based out of Brentwood, Tenn., illustrates a case where three highly advanced materials and products, improperly brought together in the common practice of flashing windows, causes all three to regress to primitive-level performance. In other words, the likely outcome, no matter how innovative each product is, may ultimately be water damage. McCampbell poses the problem this way:

With most windows installations, there are competing instructions. First, there may be instructions from the manufacturer of the peel-and-stick flashing tape. There are likely to be instructions from the housewrap manufacturer. There may be a detail from an architect. And, of course, the window manufacturer has its method. So, whose method takes precedence?

McCampbell’s answer to the question is simple. His way, which is a little of- and none of the above.

The issue is this. Increasingly, homes are systems, no longer simply an artisinal assemblage of thousand of individual pieces. Innovating a portion of a home necessarily means innovating many interconnected parts. Innovators in housing need to recognize and leverage the cluster of product players whose offerings intersect with, amplify or perhaps diminish the performance of your own item. This is what the tech innovation leaders have learned so well, not just to bring out a stunning new product, but to be the best at playing in the sandbox with others who can together make everybody smarter, faster, and more successful.

Harvard Business Review contributor Michael Shrage speaks of innovation ecosystems that have a symbiotic effect on their inhabitants and participants. Shrage writes:

While successful innovators reap new profits from new products and services, successful innovation ecosystems cultivate profitability by encouraging others to create valuable new offerings. Their financial futures depend on how innovative they make their customers, clients, channels, and partners. Truly effective ecosystems manage to turn outsiders into de facto collaborators. Enabling external innovation becomes as important as improving one’s own. In fact, successful innovation ecosystems create virtuous cycles of external creativity, which drives internal adaptation. In turn, internal innovation enables and inspires external investment.

When Apple says it is getting into the energy business are we to understand the initiative as a random new strategic push, away from the organization’s core abilities? Or, are we willing to look at the ecosystem of players, where Apple can apply its core values, and make those it connects with more successful in the bargain?

Housing’s suppliers of products and materials may suffer from being typecast in roles that serve an isolated purpose, but–as in the example of the window flashing, where flashing tape manufacturer, housewrap provider, window manufacturer, and architect might best lock themselves in a room and not come out until there’s a better solution that will prevent water damage–they need to break out of that typecasting, as do dozens and dozens of product and materials groupings that relate to one another in either the envelope or the systems of a home.

Meanwhile, here’s a look at the financial performance of a composite of home building manufacturer and materials companies, from the latest The Z Report from Zelman & Associates, which affirms an “outlier” growth narrative compared with the industry bucket’s historical performance. The Z Report notes:

Overall, while many factors have led to short-term volatility in building products demand since the recovery began in earnest in 2012, smoothed trends have remained strong and supportive of our positive cycle view. Growth this year is likely to be on the lower end of the 6-7% range that we forecasted at the beginning of the year, but we still view that favorably versus a long-term historical average closer to 3% and anticipate a similar growth profile again in 2017.”

To subscribe to the Z Report, click here.

A parting thought from Schrage that I think should make sense to players who may well be on the threshold of housing’s most innovative era in a century or more.

It’s tempting, often irresistibly so, for stewards of innovation ecosystems to want to compete against customers, channels, and suppliers when lush new savannas of profitability and growth materialize. The strategic challenge becomes resisting the urge to gobble up that opportunity, and instead identifying the partnerships that would expand it even more. Indeed, innovation ecosystems triumph over innovative companies if and when the benefits of mutual value creation outweigh the costs. That, in no small part, is why Google acquired Nest and why its ecosystem is broader and deeper than Microsoft’s or Yahoo’s. In other words, if you’re not making your innovation partners richer in some measurable way, you’re simply running an innovation factory, not an ecosystem.