Signals.

Nine out of 10 accessible “good” jobs require medium- to high-level digital chops.

As CityLab co-founder and senior editor Richard Florida notes, a growing chasm between digitally enabled workers, geographical locations, and business sectors sends a strong signal about who will win and who will lose strategically in the stretch ahead. Florida writes:

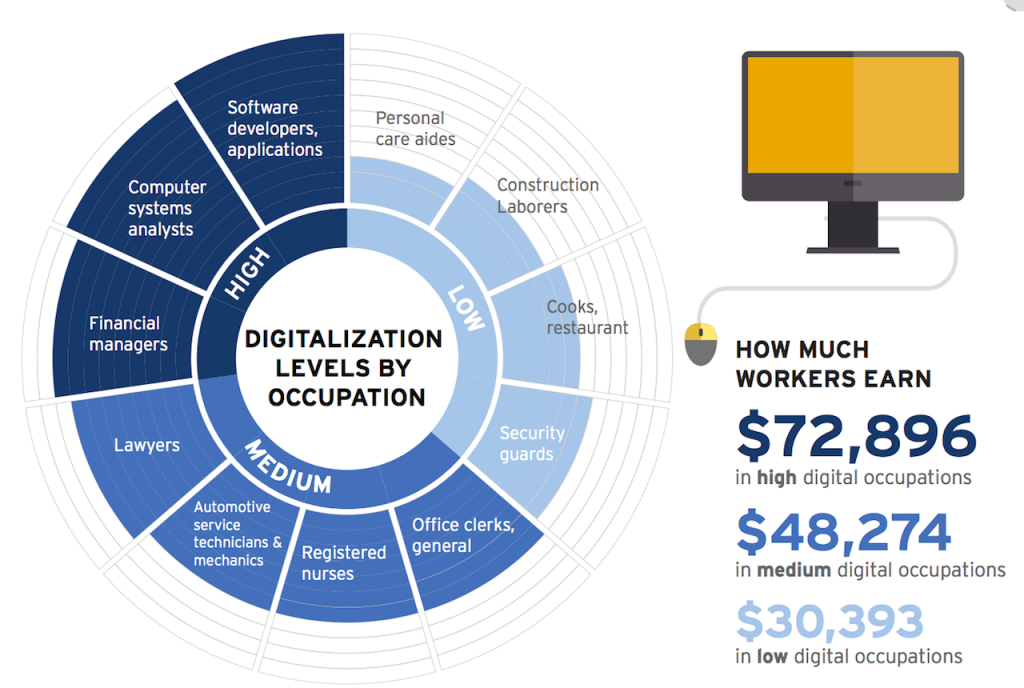

“More than 32 million workers are employed in highly digital jobs, while nearly 66 million work in medium-digital positions, and 41 million work in low-digital ones. Indeed, there has been a massive increase in the share of highly digital jobs between 2002 and 2016, when these jobs jumped from less than five percent to nearly a quarter of all U.S. jobs. Over the same period, the share of medium-digital jobs increased from roughly 40 to 48 percent, while the share of low-digital roles declined significantly, from 56 percent to 30 percent. Roughly two-thirds of new jobs created since 2010 required either high- or medium-level digital skills, and some 4 million, or 30 percent, required highly digital skills.”

Anyone still wondering why young people are not breaking down the doors to sign up to be construction laborers, who rank among the “low-digital” competence occupations?

If there is still anybody wondering that, think about this insight from the Brookings Institution authors of “Digitalization and the American Workforce,” the analysis Florida considers above.

The mean annual wage for workers in high-level digital occupations reached $72,896 in 2016, whereas workers in middle-level digital jobs earned $48,274 on average, and workers in low-level digital occupations earned $30,393 on average.

How about now? Anyone still mystified that our building trades haven’t managed to gain traction with young people as they consider a livelihood? We might rather believe that the construction labor capacity owes to the widespread end of shop classes in high school, or the pressure on everybody to go to college and get at least a B.A. degree.

Digitalization–the adoption of technologies in order to get work done faster, better, cheaper, healthier, and in greater volume–is a great social, educational, and occupational separator, marking a sharp divide between those with the strongest career prospects ahead, and those whose prospects are dim.

The divide, Richard Florida asserts, is clearest and most dramatic when you look at U.S. geography, where the diffusion of collective digital chops is choppy and lumpy from place to place. Florida writes:

Source: Brookings Institution "Digitalization and the American workforce."

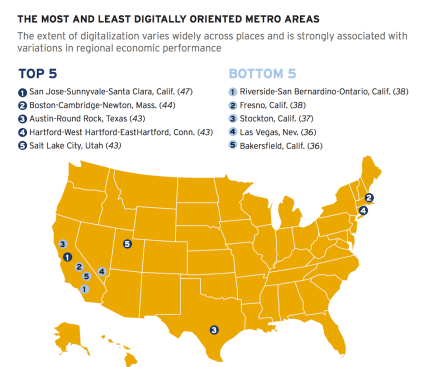

At the top of the list are the tech hubs of San Jose and Boston, followed by San Francisco, Austin, Hartford, Seattle, Madison, Raleigh, and Salt Lake City—all epicenters of the knowledge economy.

The majority of Rust Belt and Sunbelt metros have relatively low digitalization scores, although Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Albany and Rochester, New York, score quite high on digitalization. Near the bottom of the list comes Las Vegas, as well as Stockton, Fresno, Bakersfield, and Riverside—the last three of which suggest that digitalization’s divide is fractal, and occurs even within states like California, which contains metros with both the highest and lowest digitalization scores.

Now, consider occupational security. Here from Pew Research are insights about what Americans feel about how automation will transform four different areas of life by 2037 or sooner.

So, if we feel that medical treatments, retail experiences, and delivery services will be transformed by automation and technology, is there a chance in hell we wouldn’t believe that machine learning, technologies, and data will alter construction and its management dramatically?

Then why would we not begin to reset the narrative about what and where skilled construction workers’ jobs are really heading to in an increasingly digitalized reality, focusing on the adaptable proficiencies they can learn–the craft of carpentry, for instance, with a total understanding of CNC coding and operation?

This is why it’s our contention that home building’s big human resources problem of the moment is not labor capacity, but a shortage of human talent capable of and focused on using technology to a fuller capacity.

This will be a key theme of our Hive conference, coming up in just a few weeks, Dec. 6 and 7, at the Intercontinental Hotel, Los Angeles. You can register for Hive by clicking here now.