Greg Bennett steeled himself before dinner on a Saturday night in August 2015 at The Café in Atlanta’s Ritz-Carlton, Buckhead. He was preparing to say “no” to Tom Bradbury.

Easier said than done as the two go way back. In 1986, Bennett was a wet-behind-the-ears assistant builder when he joined Colony Homes, founded nine years earlier by Bradbury. Bradbury took Bennett under his wing and mentored him up the management ladder. By 1997, Bennett had risen to Atlanta region president, and when KB Home bought Colony in March 2003, he stepped up as executive vice president, overseeing KB’s new $250 million, 1,800-home Southeast division. Bradbury was largely to thank for the vaunted assignment.

Bradbury’s support was more than professional. He knew Bennett’s wife, Tammy, and he watched their two children grow up. He knew the dogs, the golf handicap, and the record of the Little League team Bennett coached. He also knew how to get Bennett to say “yes.”

Just one week before that August 2015 dinner, Bradbury and new partner and long-time friend Charles Schetter had met with Bennett at the same restaurant, asking Bennett to join Atlanta-based Smith Douglas as its momentum shifted from 11% volume gains and 22% revenue increases from 2014 to 2015, to a 26% surge in unit deliveries with 106% year-over-year revenue growth from 2015 to 2016. The two knew that with Bennett, the company’s growth could go from good to meteoric.

“We were going to keep buying him dinner every Saturday night at that same restaurant until he gave us the answer we wanted,” recalls Schetter, who himself got the same pressure from Bradbury just weeks earlier. Schetter was the KB Home business development guy who got Bradbury to sell Colony to KB in 2003. The two stayed in touch over the years on a personal level, until Bradbury asked Schetter to help make Smith Douglas an “enduring, profitable, private regional home building company.” Schetter now serves as Smith Douglas’ CEO.

The holdup for Bennett was that he liked what he was doing. He ran his own home building outfit, G. Bennett Homes, doing about 150 starter homes a year out of Atlanta’s Cartersville suburb. At the time of the second dinner meeting, he’d started 16 homes, and his college-age son, Colin, had shown interest in the business, which was doing well. Bennett liked being his own boss and the thought of having an heir to bring into the firm. Rejoining Bradbury, at that moment, felt like a risk to the life, autonomy, and wherewithal he’d achieved.

So Bennett pushed back when Bradbury and Schetter proposed he come aboard to “get the band back together.” But they had answers for every objection: suggesting that Colin might want to join the team as well; offering the use of Bradbury’s personal aircraft for visits to Smith Douglas’ five markets; assuring a work–life balance based on the idea of “breakfast and dinner at home”—the whole nine yards.

“And he looked at me with those Tom Bradbury eyes,” Bennett recalls, “and I couldn’t say ‘no.’” Bradbury doesn’t carry the title “chief culture officer” at Smith Douglas for nothing.

On the surface, Bennett said “yes” to rejoining his mentor, and to signing on with a $100 million enterprise he knew for its solid pedigree. Perhaps more important, his agreement to serve as chief operating officer was emblematic of a moment in time that gave both Bennett and Smith Douglas a future neither might have had if Bennett had said no as he’d intended.

Growth Potential

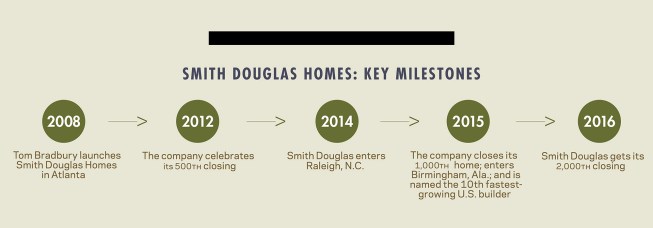

Smith Douglas sprang onto the Builder 100 in 2015, booking $89 million in revenue on 472 home deliveries in 2014. As such, August 2015 was a reckoning point. Eight hard years leading up to that time represented what the company was: a bootstraps enterprise started in the recession by a guy whose home building Midas touch moments—some thought—may have come and gone by the early 2000s with Colony’s sale to KB Home.

Check our latest Builder 100 list, say, from Nos. 70 to 100, where the firms deliver roughly 400 to 650 homes with annual revenues ranging from $100 million to $200 million. That’s squarely where Smith Douglas landed. Now look at the top 15 builders, those delivering no less than 4,000 homes a year, with revenue of over $1 billion. That’s where the Smith Douglas team believes it will be in seven years or less.

In 2016, the company closed 665 homes and generated $146 million in revenue. Take that and factor in 344% revenue growth and 501% growth in unit volume, and you’re where Bradbury, Schetter, and Bennett see Smith Douglas going. Soon.

Smith Douglas may have the opportunity to quantum leap from where it is into exclusive company among builders like Shea Homes, David Weekley Homes, and Ashton Woods Homes. These organizations share three traits few, if any, other private builders hold in common: They are established home building leaders; they are privately held and independently run; and they have access to debt market investors, just like the publics.

The Promised Land

Realistically, what are the odds smith Douglas Homes can achieve its goal?

If the company succeeds in securing institutional bond investors to pony up into a hybrid-type debt instrument that looks and acts a lot like the bonds public builders issue, its chances of hitting its ambitious plan look mighty realistic. This type of debt would fix interest rates, push back maturities to a three-to-five-year comfort zone, allow the company to buy land more strategically, and smooth what could be some cyclical hiccups over the next few years, even if long-term fundamentals look good.

Builders that have been able to access this type of capital market tend to be able to allow executives more time to do what they’re good at, which is leading home building and new community development and operations. Moreover, that resulting ability to spread new starts and completions more evenly through up and down cycles can allow for more predictable, mutually beneficial relationships with trade partners and vendors by providing transparency into an operations horizon that stretches into the future and allows for investment, inventory planning, and more efficient distribution channel management.

“Building enough equity to get access to the public bond market is basically reaching a promised land for a private builder,” says Robert Crowley, managing director at Moelis & Co. “These hybridized bonds would have a little tougher terms, higher rates, shorter maturities, and tighter covenants, but they can be very helpful for a company that wants to grow the business, buy some land, do some development. This type of debt may separate winners and losers in a downturn as well, since they can ride through a decline until demand builds up again with the extended maturities.”

Smith Douglas likely would have to take a two-step process to reach Crowley’s so-called promised land. From a net worth perspective, Ashton, Shea, and David Weekley occupy rarefied air of more than $200 million, which gets them over the minimum deal size threshold of about $250 million for a bond issue. That’s currently well above Smith Douglas’ pay grade, so the company’s strategic leaders may try to structure a junior-level deal, along the lines of what Ashton Woods did coming out of the Great Recession when it went in for $95 million in private debt in 2009. Just as lenders might look for a slightly riskier home buyer to offer a mortgage with slightly better terms to the lender, institutional investors might look at a Smith Douglas bond offering as a bet worth taking to get a higher yield on the investment.

Specifically, Smith Douglas looks to structure one of two types of investments for bond holders, giving the company financial leeway and capital for land purchases. One would be a mezzanine debt structure, with three successive years of investment, totaling $105 million with a five-year payback period. The other would be a full-stack three-year investment, for a total of $320 million with a five-year payback period.

Secret Sauce

Builders tend to give buyers at the lower tiers of the price spectrum an option between low price or choice. Pick one or the other, but you can’t have both. But what if you can?

What San Antonio legend and innovator Ray Ellison figured out in the 1950s was how to get 100% of a day’s work done—or close to it—on his home sites. Ellison sold his company, Rayco, to Kaufman and Broad Home Corp. (KB Home) in 1996, and the Rayco model became the industry standard for how to give customers both a modicum of choice about what was in their home and a price tag within their means.

By estimates of veteran Southeast home builders, there are roughly 210 days a year that you can drive a nail or put up a form. Maybe 20% or more of what could happen on those days fails to happen for some reason or other. So, for every 210 workdays, superintendents, project managers, and executives are getting only 168 days of work. Twenty percent waste is not unusual in home building, nor is it confined to home building. So what’s the best approach to the challenge of reducing waste?

While at Colony, Bradbury took a page from Ellison’s playbook and worked with a team to map every task, process, product SKU, and system into an integrated workflow tool. At the time—the late ’90s—such an endeavor seemed insane, but it allowed the staff to build houses virtually before they built them on-site.

Imagine taking a Rayco-like construction management discipline and then connecting the entire ecosystem of construction—manufacturers, materials suppliers, trades—to a single operations plan. This is what evolved into the SMART system Smith Douglas uses today, and it allows teams in their respective communities to execute on a true evenflow building model: one start, one completion, one sale per community per day, and an average three-and-a-half to four asset turns per year.

Under this system, the company can build an additional house every week of the year, and it can get each house done in 60 days or less, which is key for a builder whose No. 1 customer is an FHA buyer in its five markets. Its buyers can have choice in options, as well as a low price because of the efficiency in the executional model. What’s more, buyers can move into their home about two months from the time they pick one of Smith Douglas’ 40 models, specify their options, and get their financing in order.

Choice and a low price are not mutually exclusive if you can execute. Execution is built around mini-ecosystems of accountable project members called “R Teams,” an organization formula that Bennett and Bradbury ported over from Colony. Think of “r” words: relationship, repeatable, reliable, and you can see how Smith Douglas might structure and manage execution at a high level around this concept.

“If there’s an error causing variability to the schedule, anybody in the R Team community can pull the cord, stop production,” Bradbury says. “Everybody’s part of the community, and everybody has reason to want us to get back on our schedule-driven process. It works.”

It’s this type of organizational capital that an institutional investor might find to be compelling as Smith Douglas bids to attract hybrid bond takers. Market growth expectations in the firm’s customer segmentation wheelhouse and operational footprint aren’t too shabby, either.

The Big Bet

One of the strategic pillars Bradbury and his team baked into the company’s DNA is its customer segmentation aim to serve entry-level buyers. First-time buyers often activate early in housing recoveries as they try to get into homes before prices go up. This time, however, entry-level buyers failed to materialize as quickly.

“We lost nearly a quarter of a million dollars that first year, and we were losing money in year two,” Bradbury recalls. It took three-plus years of running in the red before Smith Douglas started to get traction.

The FHA market—those who buy a house below the limits of FHA-backed loan amounts—comprises six of every 10 homes Smith Douglas sells, and the builder counts itself as one of the largest customers of its Fidelity mortgage company partners, at more than 600 homes a year.

This market, according to Schetter, is the present and future essence of the company’s reason for being. Entry-level buyers are finally showing signs that a release of pent-up demand may have activated.

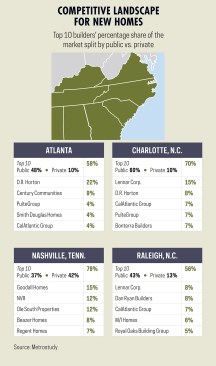

Research by John Burns Real Estate Consultants lends support to the Smith Douglas geographical footprint in the Southeast, showing that from now to 2027, the region will account for about 1 in 4 new households in the U.S. Further encouragement emerges when you zero in on the region’s most active metro areas and see that they sync up with Smith Douglas’ markets in Atlanta, Birmingham, Ala.; Charlotte and Raleigh, N.C.; and Nashville, Tenn.

More data points to the fact that within those geographic areas, it’s the FHA-qualified price points that move the fastest. No wonder, as both existing and new homes are in far shorter supply in the FHA-limit price tiers than in the move-up, second-time move-up, and luxury price tiers.

“The market’s getting saturated at above half-a-million-dollar ranges, but below $300,000, and especially in that FHA range, it’s quite robust,” Schetter says about Atlanta, noting that the market is expected to account for one out of every two homes as Smith Douglas moves toward its $1 billion revenue goal.

“Smith Douglas Homes is a fast-growth, profitable company and they’re taking a proven, scalable, and well-defined business model with a focus on cost and capital efficiency to target high-growth markets,” says Margaret Whelan, principal at Whelan Advisory, an adviser to Smith Douglas. “It’s a unique story, and investors are intrigued by it.”

Part of what makes it unusual is the way Bradbury has—in his quest to give the company a future beyond his own mortality—attracted such strong talent into the operation.

Two meetings in 2015 resulted in two big yeses for Bradbury. To show their gratitude, Schetter and Bennett will aim to make Bradbury’s dream of a 4,000-home, $1 billion enduring, profitable, and private regional home building company a reality by July 15, 2024—Bradbury’s 80th birthday.