Has news that Facebook’s user data may have been compromised and applied toward suspect ends exposed a fatal flaw in how we should look at the role of technology in transforming home design, development, engineering, construction, and capital investment and finance? And what’s all this got to do with Amazon?

Some might conclude as much, and look at proverbial Silicon Valley’s current host of high profile problems around user privacy–or the lack of it–as a cautionary tale whose ultimate moral is “do things as you always have.”

And it would be a mistake.

This week, amid ongoing turmoil in the tech investment sector and new questions as to how Facebook can or will restore itself as a “safe place” for as many as 420 million users whose data may have been “harvested” as far back as 2013, it’s come to light that fellow tech giant Amazon leapfrogged Google parent Alphabet as the nation’s second most valuable company. Wall Street Journal staffer Amrith Ramkumar reports:

“Amazon closed up 2.7% at $1,586.51, giving it a market value of $768 billion, while Alphabet shed 0.4% to $1,095.80, lowering its market cap to $763 billion. Apple Inc. has the largest market cap, at $889 billion.”

Also recently, thanks to reporting by HousingWire’s Jacob Gaffney, word is Amazon is “currently looking to hire someone to lead their newly-formed mortgage lending division.” We’ve written here and here that Amazonification in housing–as more than players in home technology, and now fintech–is not a matter of if but when.

So, now, at the moment we’re seeing Facebook, Google, Apple, and to a degree, all the innovation and great expectations they stand for held to account on Wall Street, Capitol Hill, and courts of public opinion for some of the scary and, perhaps, unintended ways their business models “mess with” how society and its individuals have looked at what’s private and what’s not, we ask the question again.

Should housing organizations’ leaders and stakeholders look at tech leaders’ troubles as affirmation that “the way we’ve always done things” is the way to go?

One thing to note, by the way, is that if you’re a going concern as a home building operator–large, medium, or small–and you go to sleep at night with some trepidation that Amazon will disrupt your business, you’re not alone.

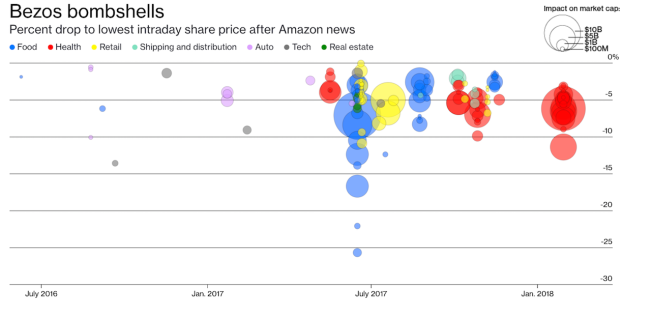

Source: Bloomberg

The company has grown so large and difficult to comprehend that it’s worth taking stock of why and how it’s left corporate America so thoroughly freaked out. Executives at the biggest U.S. companies mentioned Amazon thousands of times during investor calls last year, according to transcripts—more than President Trump and almost as often as taxes. Other companies become verbs because of their products: to Google or to Xerox. Amazon became a verb because of the damage it can inflict on other companies. To be Amazoned means to have your business crushed because the company got into your industry. And fear of being Amazoned has become such a defining feature of commerce, it’s easy to forget the phenomenon has arisen mostly in about three years.

Getting back to the question, it might be helpful to consider insight in to “why” Amazon is at least earnestly exploring entering the home mortgage business, and how that same reasoning would explain further incursion into the design, development, and construction of homes. Here’s a thoughtful take on that topic from Tammy Butler, publisher of Mortgage Currentcy.

Why mortgages? Profit margins are tight, underwriting is more complicated than rocket science and regulations are complex. Therefore, if one is a business genius as Jeff Bezos arguably is, then why wouldn’t he choose to go into other business sectors that make more money, have less risk, adapt more easily to technology and have less regulation?

I believe the “why” is a four-letter word; Data! Fintech companies are all about “Data” right now. How much more can companies like Amazon, learn about consumers to sell more product if they offer mortgages? Well, when you apply for a mortgage the lender collects virtually every piece of financial data on a consumer. Where they bank, account numbers, where they shop by debit card transactions, amount of assets, cars that they own, 401ks, where they work, their position, their income, credit scores and every little detail about their home through the appraisal. There is so much data about a consumer in just one mortgage application, it is simultaneously mind-boggling and scary. Traditional mortgage lenders have not used this data very well with the exception of those who “stay in touch” for a referral or refinance opportunity.

My own thought is that this view is very much part of the story, but misses a materially important take-away.

That is that the relationship between the enterprise, data, and the consumer is not a simple, one-way stream of activity and value. Data is a particular form of power–not just to the company who gathers it and harnesses it for commercial use–but to the consumer him or herself.

Data is like a mirror. Prior to the invention of mirrors, people had access to certain levels of awareness about themselves and behaved a certain way in relation to the world. Mirror images changed all that. From the mirror, we learn that people started looking into themselves in new, fascinating, and helpful ways.

Data is like that for people these days. From it, we can learn about and measure, and improve parts of our lives and our relationship to opportunity, to risk, to challenge, to fun, to freedom, to other values we hold dear. People and the households they make up now demand data the way they expect to have a mirror in their home.

In this way, people–whom the world of economics calls consumers–make the companies like Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, and, yes, Facebook, become the empires they are today because it’s people who want more data and go to great lengths to get it and apply it in their every moment lives. With all due respect to the brilliance of the souls who’ve started and exponentially grown our Silicon Valley culture of meteoric success, it’s their willingness to solve for consumer desires and demands–some of them unconscious–that accounts for their power these days.

So, should home builders, designers, developers, engineers, investors, and other stakeholders look at the speed bumps Silicon Valley is hitting and turn back to focus on remembering what’s always worked in the past?

Only at their peril.