“The Unintended Consequences of Law” story this month, reported by BUILDER contributor Joe Bousquin, struck a chord. It’s an analysis of the origins and five decades of gathering momentum of the rat’s nest of regulations that choke housing development for people with ordinary, workaday incomes in California.

Bousquin’s story published on our builderonline.com site just under a fortnight ago, on Oct. 13, and since, it’s become the No. 5 most popular story we’ve published since the start of 2016, with nearly 33,000 page views and an “average-time-on-page” reading that shows higher engagement than any we’ve done this year.

The article doesn’t hold out a lot of promise for the future. For those who’d like to see policy, code, and land-use fees adjust to a level where it would be reasonable to pay all those fees and take all the time it takes to secure the entitlements and still build homes that are attainable for ordinary households, California has become a pipe dream.

Still, this month, we have a new report from McKinsey Global Services, titled “Closing California’s Housing Gap,” promising “a tool kit for fixing a chronic housing shortage in the world’s sixth biggest economy.”

Builders and residential developers who’ve been operating in California will, we’re sure, be comforted to know that the good researchers and analysts at McKinsey are on the case. Ideas for action range from policy changes that would streamline permits and entitlements to tax penalties for anti-growth NIMBY municipalities. Here’s a glimpse at a couple of topline insights from the new report:

Our model also allowed us to generate detailed, local insights into who can and can’t afford housing, where they live, and how much they pay. For instance, we learned that the problem is both rural and urban: while metropolises such as Los Angeles and San Francisco suffer from high housing prices, so do rural communities such as Watsonville and Salinas, where 50 to 60 percent of households are unable to afford the cost of housing. We also learned that high housing costs not only impact low-income households, but also squeeze California’s middle class. In Anaheim, Long Beach, and Los Angeles, households earning up to 115 percent of area median income, or $69,800 per year, are unable to afford local housing costs. In the city of San Francisco, a household earning $140,000 per year, or 179% of area median income, is squeezed.

In dollar terms, we learned that each year Californians pay $50 billion more for housing than they are able to afford. In total, California’s housing shortage costs the state more than $140 billion per year in lost economic output, including lost construction investment as well as foregone consumption of goods and services because Californians spend so much of their income on housing.

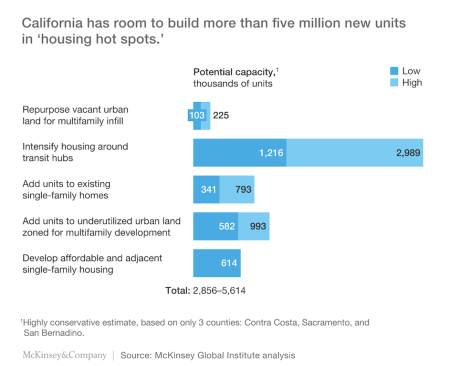

The McKinsey team put a microscope to California’s “hot spot” land parcels—its authors assert they’ve found 5 million qualifiable lots—that fit criteria for development with “attractive returns.” In particular, the analysis focuses on vacant land tracts in urban infill areas ripe for highly dense development.

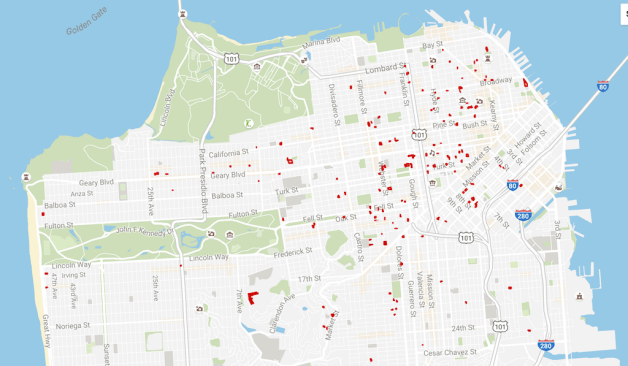

Credit: New York Times visualization

New York Times data whizzes Conor Dougherty and Karl Russell take a look at the data, zeroing in on vacancy opportunities in Los Angeles and San Francisco, where many of the 225,000 lots the McKinsey analysis says are available exist. Still, their conclusion is not entirely sanguine:

Building on these lots is easier said than done, and some plots have already been subject to controversial development plans.

And as they tend to say in our small residential development and construction community, as California goes, so goes housing.