On the outskirts of Lohja, Finland, a small, dark-clad structure quietly signals a revolution in how we build and how we live. At just 365 square feet, the Tiny House Shadow might seem modest in scale, but its ambition is sweeping: to prove that our homes can be lighter on the planet, radically resource-efficient, and even mobile—without compromising comfort or quality of life.

Designed by Matti Kuittinen, architect and professor of sustainable construction at Aalto University, Tiny House Shadow is a pilot project exploring what happens when architectural minimalism meets circular construction and new carbon-free materials. Kuittinen, who has spent years studying the emissions of different housing typologies, believes our era of sprawling homes built from virgin materials must come to an end. “We have a limited carbon budget,” he says. “Construction must learn to stay within it.”

The name Shadow comes from Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s 1930s essay “In Praise of Shadows,” in which the Japanese writer reflected on the subtle beauty of darkness and restraint. For Kuittinen, the metaphor extends further: the house is literally built from the shadows of our linear economy—discarded materials, industrial byproducts, even steel made entirely from scrap. It is, quite literally, a home built from what the world has thrown away.

This September, the project will be on public view as part of Designs for a Cooler Planet, running from September 5 to October 8, 2025 at Aalto University. Visitors will be able to tour the house and experience first-hand how architectural innovation, circular construction, and climate responsibility intersect in one small but radical dwelling.

At the heart of the project lies an extraordinary experiment in the circular economy. More than half of the building’s total weight comes from reused or recycled materials, while the rest was sourced for its minimal environmental footprint. Compared to a typical single-family house, Shadow consumes 85 percent less material, requires 43 percent less land, and leaves a 53 percent smaller carbon footprint per resident. Even its structure is designed for impermanence: the entire house can be dismantled, moved, and reassembled somewhere else. In a world of increasingly mobile populations and shrinking resources, a home that travels with its owners could hint at the future of housing.

Perhaps the most groundbreaking feature is the use of SSAB Zero™, a virtually fossil-free steel made entirely from recycled scrap. For the first time, this innovative material has been deployed in the load-bearing frame and parts of the façade, proving that heavy industry’s carbon reductions can flow directly into the construction sector. “The best building material is the one that already exists,” Kuittinen notes, pointing out that dwindling raw materials and ambitious climate goals demand radically new approaches to housing. Steel, with its durability and recyclability, becomes a critical part of this vision when produced without fossil fuels.

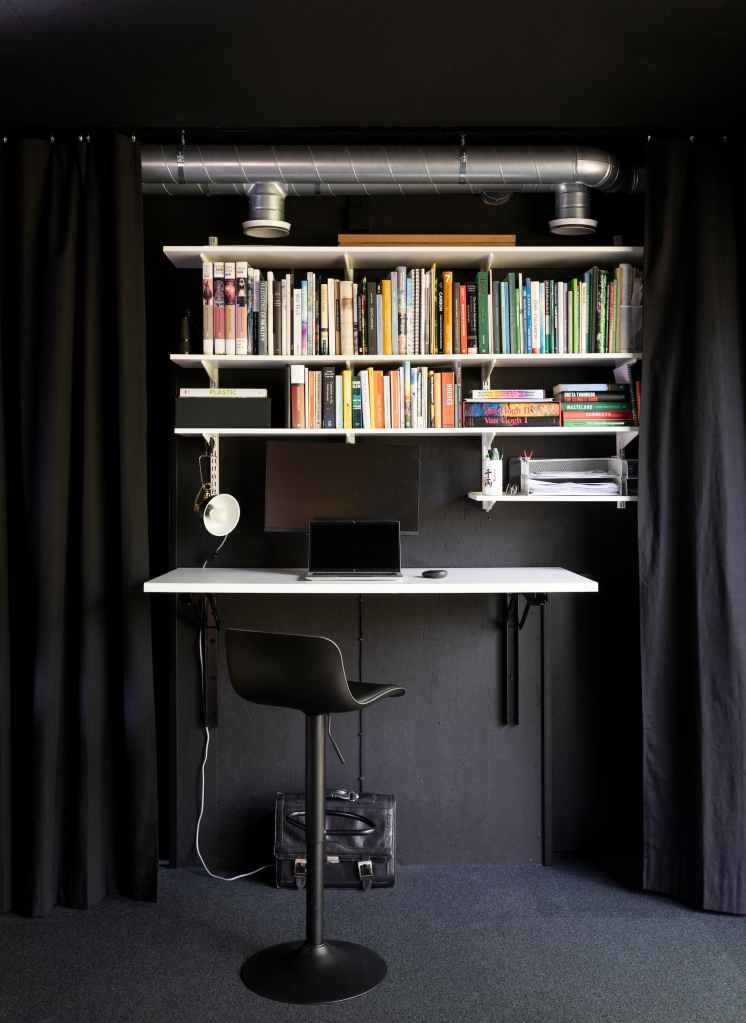

Inside, Tiny House Shadow embraces minimalism not just as a design aesthetic, but as a lifestyle principle. Kuittinen has packed surprising versatility into its small footprint: curtains allow the main living area to transform for working, dining, or sleeping; Japanese-style capsule sleeping pods stack vertically to save floor space; the kitchen dispenses with bulky cabinets in favor of open shelving, reducing material use while keeping everything in sight.

Reclaimed materials are everywhere: the bathroom and sauna floors come from recycled plastics, the insulation once served as glassware, the roof is made from old car tires, and nearly all the windows and doors have been rescued from other buildings.

Even the tiny wood-fired sauna—a Finnish essential—reflects the project’s ingenuity. At only 21 square feet, it manages to fit two levels of seating, with walls lined in discs of trees that once grew on the building site itself, creating a moisture-buffering surface that enhances the quality of the steam. Kuittinen himself plans to live in the house during parts of the research project, treating it as a living laboratory for low-emission living.

For the architect, the question is not whether people can live with less, but whether we can afford not to. With two billion new homes needed globally by the end of the century and construction emissions straining planetary boundaries, projects like Tiny House Shadow point toward a different future—one where homes are smaller, smarter, movable, and radically lighter on the land.

The house has already drawn international attention. At the New European Bauhaus Festival in Brussels, it was one of the first projects toured by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, attracting designers, researchers, and policymakers eager to see how circular construction principles could scale. For Kuittinen, this is just the beginning. “Shadow proves that recycled and low-emission materials can work at scale,” he says. “This isn’t just about one house—it’s about changing the whole mindset of construction.”

What emerges from this modest black-clad structure is not a story of sacrifice, but of possibility. “A tiny house isn’t about giving things up,” Kuittinen reflects. “It’s about rethinking what we really need for a good life—and how we can build it without breaking the planet.”