Affordability is a noun, used as a characteristic of products or services people buy.

Merriam Webster defines the adjective root of the word–affordable–as “able to be afforded,” and “having a cost that is not too high.”

Typically, rules of economics would tend to bring down the amount someone has to pay for an item or service at too high a price as a result of a natural reaction to costs that get out of balance. By increasing supply.

But if supply is under constraint as demand stays the same or increases, prices go up. Then, the cost of the good or service no longer has “a cost that is not too high.”

By definition, it’s not affordable. People would then describe its key characteristic as unaffordability.

Like housing, now. The level of production we’ve reached, post-Great Recession, is a level we’d regard as “recession level” in other cycles.

Think about it.

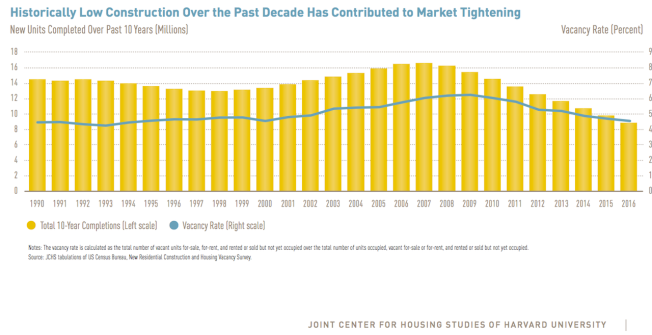

Or better yet, consider this one data point from the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies’ State of the Nation’s Housing report. In that report, JCHS managing director Chris Herbert notes that if housing behaved as it tended to do historically, the decade-long period from 2007 to 2016 would have produced 15 million new homes and apartments, not the just-shy of 9 million it did.

Even after seven consecutive years of growth, new residential construction in 2016 was well below the 1.4–1.5 million unit annual rates averaged in the 1980s and 1990s. In fact, coming on the heels of the most prolonged and pronounced downturn since the Great Depression, housing completions in the past 10 years totaled just 9.0 million units—more than 4.0 million units less than in the next-worst 10-year period going back to the late 1970s.

Supply is stuck. And that causes prices to soar past the line where “the cost that is not too high.” You hear about the construction labor capacity constraint–at crisis levels in some spots at some times of the year–and that does factor into some of why supply is stuck.

But the main reason and the most important reason is that people who live in places and own the property there would just rather not have new, less well established, perhaps less predictably well-heeled people move into their environs. They bring traffic. They bring need for more schools and school buses, and police protection, and other infrastructural support.

They add stress to what’s already stretched as far as local resources go.

Why then would they be welcome?

Nationally, shortages of housing in the 1 to 2 million range of for-rent properties and close to 2 million more in single-family for-sale units are driving prices beyond a “cost that is not too high.”

But still, locally, local tax payers wait too long at a traffic signal to get to the market; or they wonder who’s vandalizing the mail boxes; or they get an assessment for new school buses for the junior high school, or they have to pay higher town taxes for additions to the police or highway departments.

More people, especially people who are just starting out in their careers, are only going to add to all of that pressure on local resources. They’ll also be more likely to move faster because they need more flexibility in their jobs and career paths these days. What’s more, they don’t have the deep regard for the place that people who’ve been there, and committed themselves to the community have.

They’re strangers.

This is why we’re heartened to see this story, about the Yes In My Back Yard movement. People understanding that fresh new blood and new voters and young adult residents are the way to infuse communities, not only with a workforce, but with a future leadership.

A year ago most Yimby groups were tiny ragtag operations, but today they are pushing bills in Sacramento and have attracted enough money from Silicon Valley and elsewhere that many activists have been able to quit their day jobs to do politics full time.