It’s the land use policy, stupid.

This is why study after study, economist after economist, analyst after analyst will conclude that there’s a housing shortage in many of America’s towns and cities, and that shortage is causing housing prices to leap faster than job creation and household earnings can keep up with.

It’s why developers and builders and any professional who engages in residential real estate inevitably will come back to the truism, real estate is local.

It’s about the dirt. Each piece of dirt comes to its owner(s) with its own set of special instructions, ranging from physical and environmental conditions to abstract legal ones that reflect the wishes and policies and literal laws of the land.

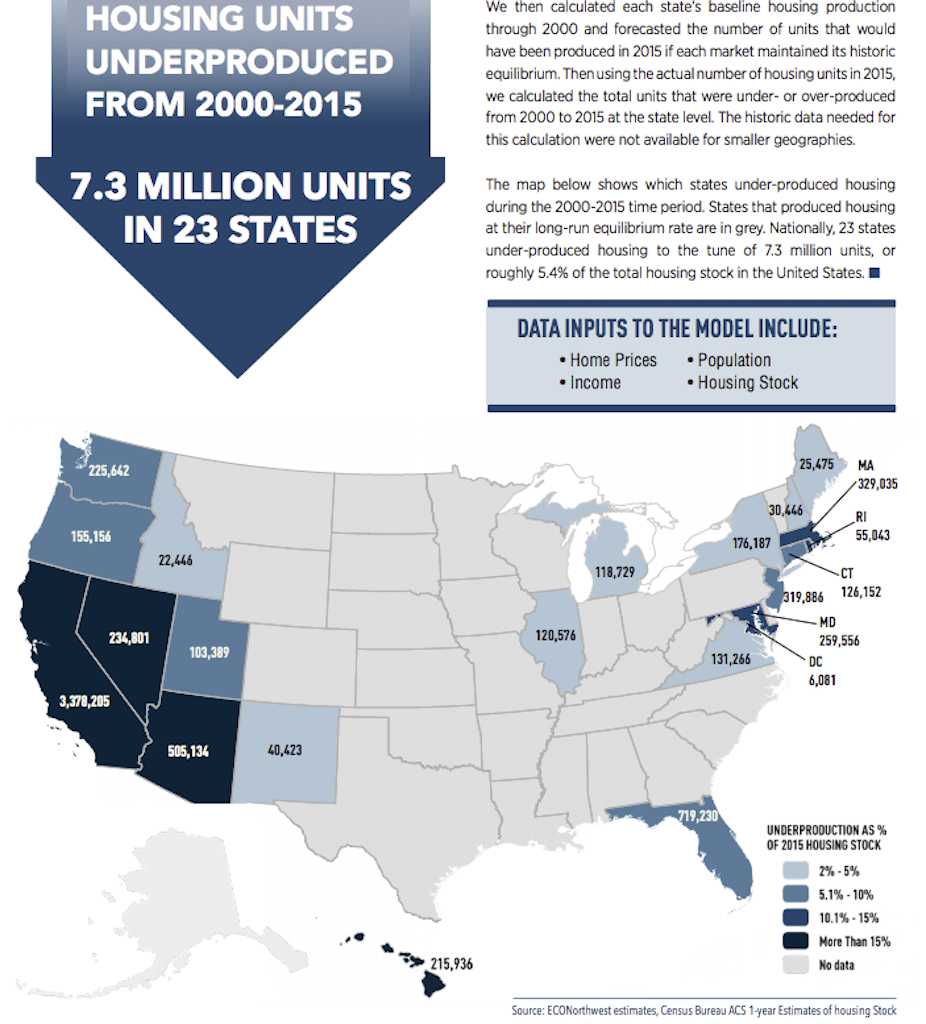

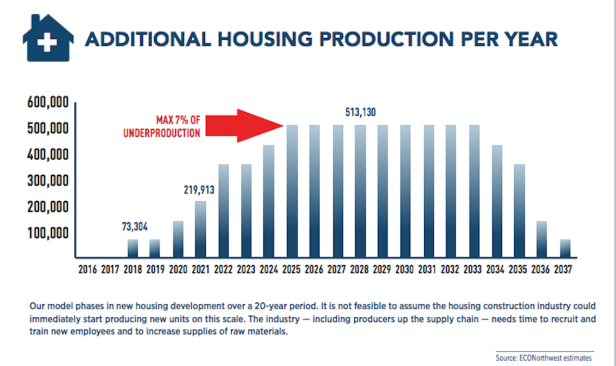

For more evidence of this, a new study released yesterday from the Up for Growth National Coalition, ECONorthwest, and Holland Government Affairs proposes to quantify the magnitude of the housing shortage for the duration 2000 to 2015. The math–which asserts that 7.3 million rental and for-sale units that did not get built during that 15-year period–suggests those “missing units” as the root cause of a host of big and growing challenges, both local and national. The report notes:

In addition to increasing rents and home prices at an unsustainable level, failure to meet housing demand has other negative societal impacts, including suppressing national GDP, generating negative environmental impacts, and pushing individuals and families with limited incomes farther away from job centers.

Fact is, if you do the math slightly differently, you might easily calculate that the “pent up” supply of homes not built between 2000 and 2015 exceeds 7.3 million. Look instead at historical averages of about 1.3 million housing starts annually, factor in a few years of wild overbuilding during the middle part of the last decade, and virtual radio silence for a couple of years coming out of the Great Recession, and your answer might be closer to 10 million single- and multifamily, and manufactured home starts that didn’t happen during that time period.

California, which came out of the Recession producing jobs and wealth acutely disproportionate to the amount of housing activity, is the reluctant poster child for communities whose residents want to shut the gate to further residential development. Those towns and cities and their elected and appointed officials fear that more housing means more of everything bad, and a depletion of everything good.

The Up for Growth National Coalition data makes it clear that California is only part of the problem, and that communities across the nation are doing their very best imitation of California when it comes to considering, supporting, permitting, and investing in housing growth to keep balances between supply of units and demand for them. Here’s Wall Street Journal correspondent Laura Kusisto’s take:

“The artificial barriers to housing production aren’t constrained just to California,” said Mike Kingsella, executive director of the Up For Growth National Coalition. “As we dug into the numbers behind this, at a local market level, we’re seeing a pronounced affordability challenge in places like even Arizona.”

Arizona and Utah are among the states that have built too little housing in the 15-year period, according to the report. The shortage in these places likely reflects strong demand as they become top destinations for retirees and people priced out of the Northeast and California.

At the same time, it is becoming more difficult to build all across America due to shortages of land, labor and materials.

But labor and materials constraints are ephemeral. Land shortages, and the land use upward spiral of regulatory constraint are not temporary.

Not for nothing, the National Multifamily Housing Council and National Apartment Association have recognized–via research the two organizations conducted with Hoyt Advisory Services–that developers will need to add 324,000 units annually for the next 12 years to make up for lost time and keep up with new household formation.

Source: NAA and NMHC "We Are Apartments" site.

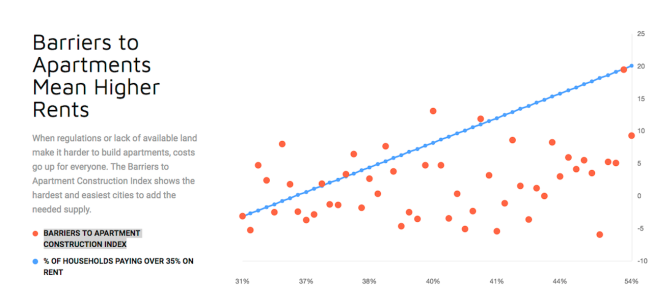

The NAA and NMHC have gone so far as to develop a Barriers to Apartment Construction Index, which scores 50 metro areas on a scale of difficulty posed by regulatory and space constraints. A score of 19.5 ranks as the most difficult market to add apartments, Honolulu.

It seems evident that multifamily developers have jumped a step ahead of their single-family for-sale siblings, both in investing in research that begins to build evidence around the scope of the shortfall and developing scenarios for getting beyond the current impasse, which is a lose-lose-lose proposition.

The upshot of anti-growth initiatives, whether it’s next-door neighbors, activist advocacy groups, officials, etc., is a set of intended and, perhaps, unintended consequences. It’s these unintended consequences that could imperil the very values antigrowth proponents say they champion.

One way that it appears multifamily players seem to recognize as a solution–better on the whole than single-family players–involves a form of collaboration that’s been around for as long as people have been forming communities as a way to live and conduct business: public-private partnership.

Such partnerships, if they’re real and sustainable, answer the “what’s in it for me?” question on both sides of the deal. That means not only providing evidence that can be persuasive, but unlocking the power of the meaning of that evidence.

Facts and data can win an argument, but they don’t measure up when it comes to the “what’s in it for me?” question. They don’t move people to want something different for themselves.

“Housing Underproduction” and even the terms “housing crisis” or “housing shortage” are not a product that will move an individual or a voter base or a local municipal board to treat a matter differently than they otherwise would have.

Public-private partnerships have to confer a basic benefit value for both sides to be real, and not just leverage a vague future risk as part of that benefit.

Single-family for-sale communities, including the new ones, make for some of the best stories that can be told. For families, friends, getting to work, for access to schools, to healthcare, to nature, and to basic connection to what people need, what builders make as they invest capital in land, materials, construction teams, and talent to develop neighborhoods makes a narrative that can be the “what’s in it for me?” answer people demand.

Builders have mostly been good at doing what they do, not necessarily capturing the story of what happens after they do what they do. This may have to change if builders are going to have any role whatsoever in reversing a tide of opposition to residential growth in cities and towns near you.