“That’s not an area that the private sector, free marketplace will be able to solve. That’s up to the politicians and local agencies to figure out.”

The “that” in this case addresses the fact that today’s housing market dynamics are pricing out more and more people essential to more and more local markets’ capacity to operate safely and effectively, to educate kids, to staff restaurants, and more.

Speaking was the top executive of one of the largest housing and real estate organizations in the country.

“That” part of housing’s unmet need, a growing population employed people, making what would be considered the area’s normal income levels, and doing jobs those cities and towns regard as essential to their day-to-day ability to keep order and thrive, doesn’t figure into this huge company’s strategy today.

Understandable. And sad.

Battling local jurisdictions at every turn, paying exorbitant fees and awaiting frustrating and costly amounts of time for approvals, and dealing with resident groups who are the opposite of welcoming becomes distracting, and unproductive. To any degree possible, residential developers and builders seek opportunity elsewhere, where navigating fees and approvals presents a “normal” level of obstacles and impediments, but where efforts and community outreach are fruitful.

Still, in an increasing number of metropolitan areas, the level of effort goes up, and the cost and time for approvals, entitlements, inspections, etc. go up, and the ability to build and develop gets squeezed.

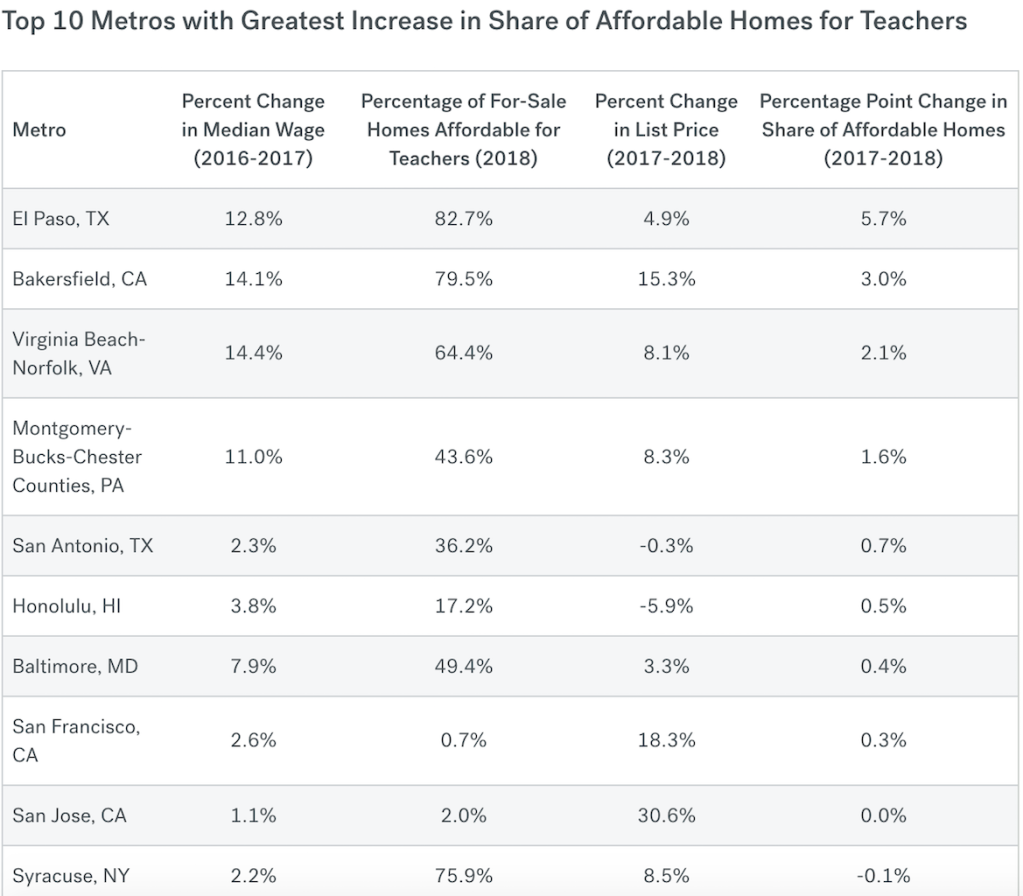

This analysis from Trulia senior economist Cheryl Young, comparing median home prices in markets with occupational income data from the latest Bureau of Labor Statistics jobs report, tells a gory story about how even good jobs don’t measure up to what it takes for people in them to get access to homeownership in or close to the community they work in.

- Teachers are worse off or the same in 85 of the largest 93 metros, where the share of listings that teachers can afford decreased or held steady since this same time last year. And in the eight metros where the share of affordable listings increased, only four increased by more than 1 percentage point.

- First responders have the toughest time finding a home they can afford to purchase in expensive California cities. Despite earning more than $100,000 in San Francisco and San Jose first responders can afford just 2.4% and 6.6% of currently listed homes, respectively.

- Restaurant workers, as the lowest wage earners among the occupations studied, continue to face the greatest challenges when it comes to affording a home. In 61 out of 93 markets this year, the share of homes affordable to restaurant workers is in the single digits, up from 56 markets last year.

- Computer programmers have been at the center of a conversation about housing affordability and increasing scarcity in tech hotspots like the San Francisco-Bay Area and Seattle. But they, too, were unable to afford a majority of homes in these markets. In San Francisco, San Jose, Calif., Oakland, Calif., and Seattle programmers earned six-figures but could only afford 4.8%, 11.8%, 19.7% and 39.0% of all homes, respectively.

Voters and the officials they elect into office to serve their interests in matters of local community law and direction don’t have such a great track record at taking a long, healthy, constructive view of resources and how to sustain them over time. Any scenario that suggests growth comes with negatives–traffic, school costs, rising crime, pollution, noise, you name it. Scenarios that limit or eliminate growth reduce the odds those negatives will gain ground.

How’s that working for towns and cities over time? I guess we’ll see. Priced out–essential workers may gravitate to places they can afford to work and live. Somewhere else. That’s where things are headed, because as that CEO of one of the biggest home building companies in the country told me, it’s not a matter private enterprise organizations are going to play a part in solving. The specter of out-migration among would-be residents is already becoming a reality. What if private sector organizations, making business decisions that make the most sense for their stakeholders, collectively abdicate urban downtown areas, leaving them exclusively to high-end luxury developers who can make those hairy, brain-damaging deals pencil profitably?

Something’s got to give.