Do you really believe the market is undersupplied? By how much? What exactly happens when an undersupplied housing market collides with rapidly deteriorating financial conditions? How does that play out?

Those are the fundamental questions of our times, and the answers aren’t immediately obvious. But if you look to history, there is precedent for the situation we find ourselves in.

Do any of these conditions sound familiar?

- Housing boom, amid three-year undersupply of homes

- Labor costs at mills +19% per hour

- Surge in lumber prices, followed by rapid decline

- Double-digit inflation

- Product shortages, with delivery delays pushed out over a year

- Surge in production and buying to backfill inventories

- Federal Reserve raised interest rates +350 basis points in eight months

- Recession preceded by international conflict and pandemic?

That’s a list of market factors from 100 years ago, describing things as they were from 1919 to 1921.

After a brief slowdown at the end of World War I (and a pandemic), builders struggled to keep up with housing demand. Amid a postwar surge in credit, consumer spending rebounded, and housing found itself three years behind in construction. Prices for lumber jumped 2.5x higher than normal, and product shortages abounded. Contractor labor was in tight supply.

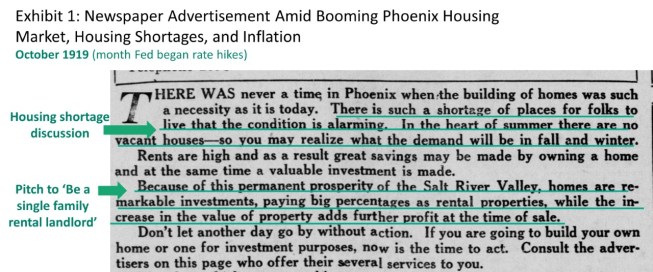

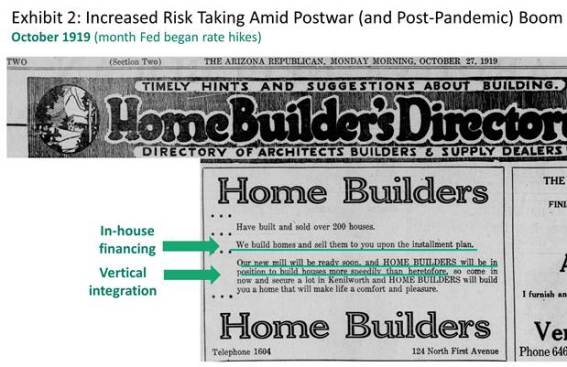

The feeling of the housing market in 1919 could also have been quite like 2022. Below are two housing advertisements from October 1919. You will note the pitches for build-to-rent, local market undersupply, along with aggressive in-house financing and vertical integration leading to faster cycle times. Similar, indeed, to housing discussion today.

What happened in 1921? Rapid tightening, a financial slowdown, a brief depression, and, yet, housing did surprisingly well.

In 1921, the still-young Fed fought inflation for the first time, ever. The goal was not so much “price stability” like we have today, but instead to “bring prices down,” and the Fed succeeded. Wholesale prices collapsed more than 35%, along with lumber. Financial markets collapsed, riots and protests occurred in the streets.

So how did it turn out for housing? Better than many expected.

Housing fell 22% in the same year rates surged by 350 basis points. However, once prices stabilized and financial conditions started to ease, housing volume surged again. It was up 81% one year later, with continued growth in the years to follow.

What happened over the following five years in housing was striking (it was the roaring ‘20s after all). Excesses occurred in all forms of consumption, including outlandish housing developments, particularly in Florida. It wasn’t sustainable or advisable, but the inertia was hard to stop. There must be something psychological about forcing a generation to undergo a housing shortage amid a pandemic, a great war, and then a financial crisis.

Construction excess from this “bounce” even showed up in literature and pop culture. F. Scott Fitzgerald authored his great novel “The Great Gatsby,” presumably after attending parties in 1922 (the year after the broader economic downturn), when financial conditions began to ease and housing starts surged.

The excess in construction and consumerism was expressed in these words:

The parties were bigger

The pace was faster

The shows were broader

The buildings were higher

The morals were looser

And the liquor was cheaper

What does it mean?

Think carefully about your undersupply belief, and choose your historical precedent carefully. There are plenty of differences between today and 1921. Back then there was no official measure of unemployment, no comparable quality measure of GDP, and certainly housing data was thin at best.

However, we do well to think about what the precedent in the data might be. Just because our Bloomberg terminals and census data go back to only 1959 doesn’t mean that those are the only cycles we should think about.

What we learn is this: If you really believe there is an undersupply of housing, you need to stretch your historical analysis back to 1921, because it is one of the few historical cycles with both underbuilding and serious financial carnage.

I suspect the undersupply calculation will vanish temporarily (like it did in the 1980s before headship rates later rebounded), before jumping again. In any case, once financial conditions begin to ease, the size and shape of the bounce is more important to think about today than it has been in quite some time.

And if historical precedent tells us anything, it’s that once prices stabilize, bounces in demand are typically stronger than most forecasters expect today.