Bill Timmerman

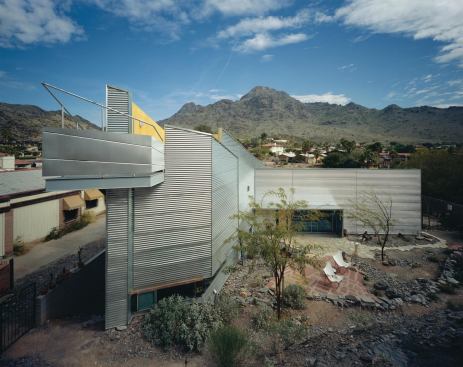

A five-unit live/work project in Scottsdale, Ariz., Loloma 5 ref…

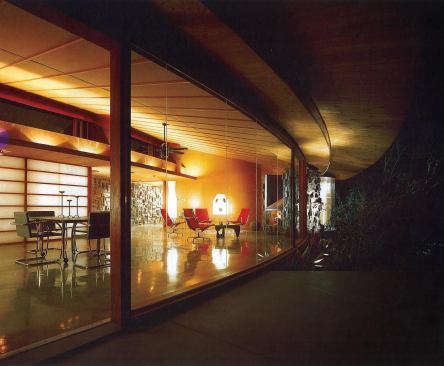

On 10 acres of desert 30 miles from downtown Phoenix, the house consisted of two metal-clad modules—truncated wedges in both plan and section—joined by a covered dog trot. “Budget will drive geometry,” Bruder says, and the budget on his own house was only $10,000. With the greater latitude later commissions would provide, he was more apt to lay out a plan in flowing curves that followed the site’s contour lines. In every case, he explains, “the work grew from the ground up, from this interpretation of the site.” His manipulation of material and space better reflected the optimism and ambition of early and mid-century modernism than it did the prevailing attitude of his own generation of architects. At the time, Bruder recalls, “Post modernism is in the air, but I’ve come up outside of academia. I’m basing my hero worship on Wright and [Bruce] Goff and Lautner and Paul Schweikher. That’s my cast of characters. I like this work; it makes sense to me.”

straw into gold

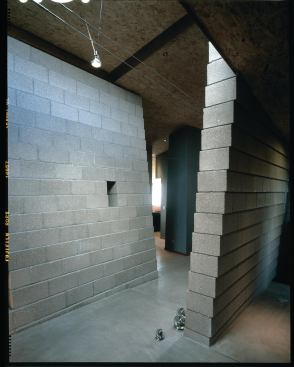

Respect for his elders, however, never lessened Bruder’s passion for moving the work forward. His early efforts, he says, were driven by “bravado, intrigue, and the interest in pushing the material.” And he’s always had the sculptor’s alchemical gift for ennobling the commonplace. Central to his approach, he says, is “how you celebrate the materials and how they go together. And how they go together, often, is the joint as a void.” In the Nellis/Cox Residence (1988–2000), he met a tight budget by specifying walls of discarded broken concrete blocks instead of stone. The resulting jagged, deeply shadowed surfaces contrast strikingly with the plan’s flowing lines. His most recent work is more refined in texture but still uses materials to enclose space in ways that transform and elevate both.

“He’s a very special American architect,” says Peter Q. Bohlin, FAIA, of Bohlin Cywinski Jackson (BCJ). The two met in the mid-1990s when Bruder visited BCJ’s Ledge House in Maryland (he would later write an introduction to the firm’s book on that project), and they have followed each other’s progress ever since. Bohlin observes of his friend’s work, “It always seems fresh, personal, strong. He’s always fiddling with new materials. The work is sculptural—fully—and very inventive. He does very special houses—and they’re Will’s houses.” But that personal quality emerges from a deep, broad interest in the work of others, Bohlin notes. “He’s constantly visiting and studying, to an amazing extent.”

Of his many trips abroad, Bruder views the Rome Prize sabbatical in 1987 as a singular watershed in his career. For six months he traveled the length of Italy, studying “the effect of material and craft—from the Etruscan to the Roman—on 20th-century modern architecture, culminating with the work of Carlo Scarpa.” In retrospect, he distinguishes between his pre-Rome and post-Rome buildings, the latter being not only “finer grain in scale than the earlier work,” but also “more of the vernacular and the context.” After his return from Italy, Bruder’s context shifted increasingly from the desert to the city, most notably in his design for the Phoenix Central Library.

city life

Bruder’s residential work would be enough to establish him among the leading architects of his generation, but it is impossible to ignore the impact of what David D. Salmela, FAIA, calls “that amazing library in Phoenix.” Bruder had done public work since his days with Birkerts, but the Phoenix Central Library cemented his reputation as a civic architect. The building, which rises from the cityscape like an urban mesa, culminates in a vast reading room whose soaring concrete columns support a light tensegrity roof structure. At the solstices, sunlight pierces the roof’s circular skylights, illuminating the column tops. The event has become a biannual civic ritual.

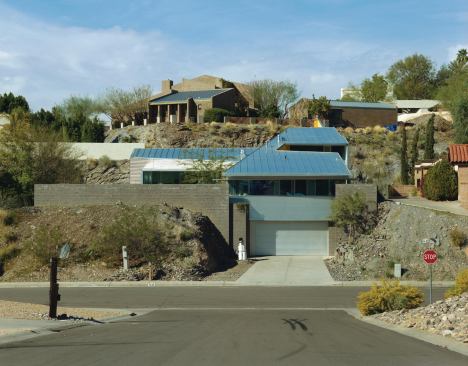

Bruder followed with a series of residential projects that reflect a growing interest in the urban environment. In the Hill/Sheppard House (1993) he sought “a total merging with the context, almost an effort to make the house invisible.” But rather than the open desert, the context here is a leftover site in a closely packed suburban subdivision. Put to this very different kind of test, Bruder’s intricate folded-plane geometries define private spaces and frame distant views amid a clutter of neighboring buildings. Multifamily projects like Loloma 5 (2004) and Mezzo (2008) represent steps toward a livable, walkable future for one of America’s most car-centric cities.

Single-family and multifamily alike, all Will Bruder + Partners projects benefit from the founder’s full involvement, including his trademark on-site improvisational design. As lead designer on every project—and the tally now exceeds 600—Bruder handles primary client contact, presenting each proposed design in his own hand-drawn sketches. But while he stands at the center of the process, he is generous in nurturing the talents of his associates. Counting among his former protégés Wendell Burnette, AIA, and Rick Joy, AIA, Bruder says, “I take great pride in my studio. I think it’s a teaching studio, a mentoring studio.”

“There’s a bunch of guys in Phoenix who flat-out want to be him,” says Joy. “The thing about Will is, he’s enormously generous with his belief in architecture, what it can do for people, its uplifting possibilities.” For Bruder, at 65, those possibilities have never been greater. “I’m excited about what I do,” he says. “It’s my sport; it’s my passion.” He brings to each new project “all the things I’ve learned from all these buildings I’ve had the privilege of enjoying.” The attraction that first drew him to a Frank Lloyd Wright construction site more than 50 years ago retains its magnetic force. “It’s about capital-A architecture. You’re getting paid to open the possibilities of what architecture is about.” And the goal of architecture, he says, “is to build a better world to live in, to build armatures for memory. And memory is what people value more than any physical thing.”