If one were to designate an official residential style for the New England coast, Shingle style would have to be a front-runner for the title. Originating in the 1880s, the style has enjoyed such a robust revival since the late 20th century that it bids fair to join the Cape, center-hall Colonial, and bungalow as an ageless, perennial American house type. At first glance, this new vacation home on Maine’s Down East coast looks like another well-executed variation on the classic theme. It has the balanced, asymmetrical massing, the broad-shouldered main roof and mix of dormer shapes, the cedar shingles on walls and roof. But the longer one looks at this building, the less it looks like a straight-ahead Shingle house. Absent are the heavy, painted trim assemblies, the massive columns, and the palatial scale also typical of the breed.

The detailing is almost Modernist in its simplicity. Step inside and the matter becomes clear. In this spare, restrained interpretation, architects Libby and Matt Elliott have distilled Shingle style to its essential elements without betraying its spirit, producing something reassuringly familiar yet also refreshingly new.

The Elliotts are uniquely qualified to produce such a design. Their firm, Elliott Elliott Norelius, is stylistically ambidextrous, rendering traditional building types and Modernist originals with equal facility and conviction. Both threads of their work show a deep sensitivity to the natural environment and architectural history of coastal Maine. “It’s a big dialogue in our office,” Matt Elliott says. “How do you fit in where you are without just copying? It’s always a struggle.” A Modernist reinterpretation of Shingle style settles that question rather neatly. “It is one of those buildings that let us incorporate both sides of our office in one building.”

The Builder: Close to Home

There may be sources of stress in Peter Woodward’s life, but the morning commute isn’t one of them. His company’s shop and office are out back of his parents’ 200-year-old house in the coastal village of Sedgwick, Maine. He doesn’t even have to cross the road to get there. “I can walk right over the hill,” he says. “My dogs are here every day.” Woodward grew up in that house, and he’s worked for his father since before he was grown. “I’m 33. I’m probably the youngest guy on the crew, and I’ve been here the longest.” His grandfather worked for a builder down the road in Blue Hill, as did his father, Jon Woodward, until he founded Jon D. Woodward & Sons in 1976. Peter built his first new house in 1992 and has built at least one each year since. The picturesque home-town setting remains much as Woodward has always known it, but beneath the surface things are changing. Rising property values have led most of the old neighbors to sell out and move inland, where taxes are lower. “There’s less and less local people and more and more retirees,” Woodward says, and the company’s work reflects the change. “There are bigger projects around. Houses are more defined to individuals.” Woodward and his father split the project list down the middle, with the younger man heading up the more eclectic, architect-driven projects. “We enjoy building traditional Maine-cottage buildings,” he says, “but we will do anything.” And in that respect, things haven’t changed at all. Sedgwick is still at the end of the road in a quiet corner of the country, a place where earning a living has always demanded flexibility. “All of our 12 guys, you could put them on a foundation and they could build it to the last doorknob,” Woodward says. “We do everything—roofing, siding. We work for local people who need a door shaved and build multi-million-dollar projects.”

But the formula emerged as much from client interest as from the architects’ philosophical debates. Tired of the constant upkeep on the old farmhouse that had been their longtime summer home, the owners had found a fine shorefront lot that seemed to call out for a Shingle-style house. But, while they wanted a house that acknowledged the “cultural history” of the region, Elliott says, “They didn’t want it to be this pretentious Shingle-style house. They wanted it to be more casual, almost stripped down.” In browsing through a book on the style with their architects, “The images they kept coming back to were the carriage houses and the kitchens in these big Shingle-style mansions.” The carriage-house scale fit their needs, and the utilitarian aesthetic—the simple millwork, slate sinks, and exposed steel beams—suited their taste. Avid art collectors, the owners wanted their summer place to be as much a backdrop as a showpiece, Elliott says. “We also felt that when it was stripped down it would be a better showcase for their stuff.”

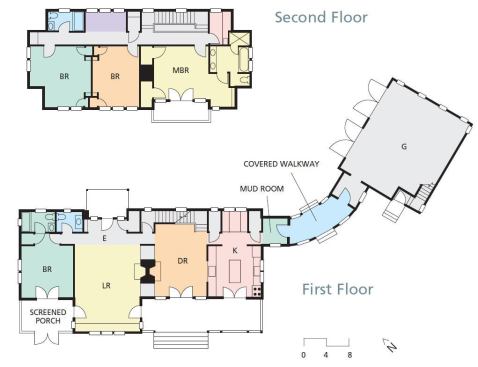

Here, however, stripping down is more than a mere process of subtraction. At the first floor, service and circulation spaces line up neatly along the inland-facing wall, while the major rooms—kitchen, dining, and living rooms, a guest bedroom—open onto covered porches and a meadow-like yard that stretches down to the shore. The architects ordered the first-floor plan around an exposed structural-steel frame that serves as a link between the Shingle-era utility buildings that inspired the house and the Modernist buildings that followed them (see “Framed Art” sidebar). “The rigor of the plan sort of came from the steel frame,” Elliott says. The profile of the I-beams and the frame’s bolted connections also add a bit of visual interest at the wall/ceiling juncture. Onto that structural—and thematic—framework, the house hangs elements drawn from both Shingle and Modernist vocabularies, which blend in a surprisingly natural way. The pickled fir beaded-board ceilings are a classic cottage touch, as are the kitchen’s slate countertops and nickel cabinet hardware. The bright-finished mahogany stair rails, vanities, and accents are an unmistakable reference to the wooden sailing yachts native to these waters. Eight-over-two double-hung windows also bow to tradition. But the openness and strict rationality of the plan are straight out of the Modernist playbook, as are the tasty, low-fat trim details. Windows and doors get by without casing. Porch columns are black-painted steel pipe; roof brackets at the second-floor porch, painted steel plate.

Details: Framed Art

Most custom homes are full of structural steel—the loads and the spans demand it—but it is most often hidden behind plaster or boxed in with wood. In this house, architects Libby and Matt Elliott took the opposite approach, not only exposing the steel beams, but also using steel even where it wasn’t strictly necessary. “A few of those beams really could be wood,” Matt Elliott admits, “and we could have had a couple more columns …” But the stalwart, orderly framework overhead holds the house together both visually and structurally. From a construction standpoint, burying a few I-beams behind the Sheetrock is a lot easier than showcasing them, but the frame itself went up without a hitch. Peter Woodward decked over the foundation, leaving cut-outs for the first-floor steel columns, and subcontracted the frame to a steel-erection company. “It took about two weeks to set up,” he says, “and then we were back to our deal.” The fussy work consisted of running finish materials up to the steel while leaving constant, precise-looking reveals. More important was preventing ruinous condensation by isolating interior steel from the cold outside. While beams appear to penetrate the outside wall to support the porches, Elliott points out, “Whenever we went from a cold space to a warm space with that steel we had to have a thermal break.”

Ideas like those look great on paper, but projecting them in three dimensions takes a builder with the skill and patience to work through details that have never before seen the light of day. The Elliotts knew just the guy. Peter Woodward comes from a long line of Maine housewrights (see “Close to Home”). He grew up five miles from this site, taking apart and rebuilding classic old buildings. He knows and admires the way the old-timers built. But he also spent a little time up the road at the University of Maine, studying mechanical engineering, and he’s game for the more individualistic houses that make up more and more of his company’s job list. Woodward points out the crown molding he steam-bent for the fascia of the curved covered walkway to the garage and the casing-free interior door frames, whose jambs he fitted only after the rough openings had been wrapped in gypsum board, both easier drawn than built. But while he is happy to discuss the challenges of realizing the Elliotts’ very particular vision, he is equally focused on the nuts-and-bolts performance of the building. Vacation homes may enjoy the easy life when their summering owners are in residence, but they must fend for themselves through the winter. And the open stretch of salt water that makes this site so appealing in the warmer months can deliver a load of off-season abuse. “In the winter this place gets pounded,” Woodward says. “Not much snow, but wind and rain,” a real test for windows and the integrity of the building shell. Along the coast, sites also tend to be ledgy, wet, or both. To handle a high water table, Woodward ran footing drains both inside and outside of the foundation, and he reports that the basement stayed bone dry during the wettest fall in memory.

Which is all to the good. Because a design that looks this good and works this well merits a quality build that will see it through many decades of use. The longevity of successful architectural styles can be interpreted as an effect of natural selection; the fitter ones stick around and, by influencing later buildings, reproduce themselves. The oldest Shingle-style cottages up and down the coast are now well into their second century and far outnumbered by their architectural descendants. This new house, which infuses the lineage of the first-generation originals with the new blood of Modernism, looks like an adventurous young branch on the old family tree.

Project Credits

Builder: Jon D. Woodward & Sons, Sedgwick, Maine; Architect: Elliott Elliott Norelius, Blue Hill, Maine; Living space: 3,000 square feet; Site: 4 acres; Construction cost: Withheld; Photographer: Brian Vanden Brink (except where noted).

Resources

Bathroom/kitchen plumbing fittings/fixtures: Chicago Faucets and Toto; Dishwasher: Asko; Entry/interior doors: New England Screen Door; Lighting fixtures: Abolite, Lightolier, and Stonco; Oven: Wolf; Patio doors/windows: Marvin.