Building in traditional Southwestern styles has never interested Tucson, Ariz., builder Page Repp. Nor has it ignited creative excitement in the minds of architects Luis Ibarra and Teresa Rosano, also of Tucson. All three admire the old adobe and Spanish Mission-style structures in and around the city, but they’re Modernists at heart.

Ironically, they’ve collaborated on a Modern house that respects regional architectural traditions far more than any stylistic imitation could. Its floor plan, relationship to the land, and low-tech cooling strategies all make it a natural descendant of the original adobe buildings in the Presidio, Tucson’s historic quarter. “The historical references aren’t intentional,” says Ibarra. “They’re just what made sense in this situation.”

The client first approached the husband-and-wife team of Ibarra and Rosano after seeing a story about their design for their own kitchen in a local paper. The pair knew Repp from their college days at the University of Arizona’s architecture school; Ibarra graduated in 1993, Rosano in 1994, and Repp in 1997. Now Repp runs his own construction company, where his design training is a major asset to his working relationship with high-end, custom architects like Ibarra and Rosano.

The Builder: Double Identity

When Page Repp (below, far left, with staff) wanted to design and build his own house as an undergraduate at the University of Arizona, his architecture professor told him he’d never be able to do it. Repp had already started a construction company halfway through college—obviously, he’s not one to back down from a challenge. He did complete the house, which he designed as a Modern prototype for affordable, low-maintenance housing. In fact, he used it as his senior thesis project.

After graduating, Repp decided to stay in the hands-on side of the building business. “I’m not as comfortable in the office as I am in the field,” he says. “Eventually I want to get certified as an architect so I can do more design/build.” He’s also adding developer to his list of professions. Next door to his house he built and sold another version of the prototype, and two more are under construction nearby.

Repp’s strong reputation among lenders has helped his clients and collaborators get loans for the buildings they want to do. And his design skills add value to a project. Because of his training, he can visualize a detail the way an architect does and decide how to build it with a contractor’s mentality. “We all work as a team,” he says of the houses he’s done with Ibarra Rosano and other Tucson architectural firms.

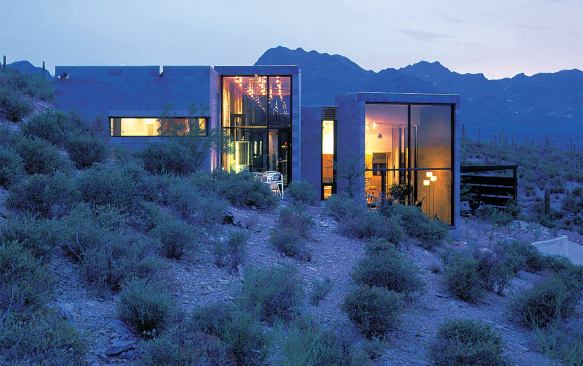

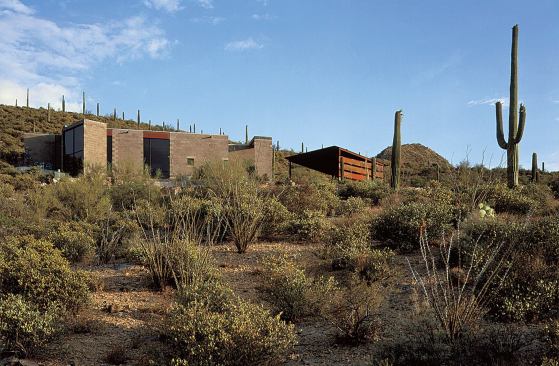

Both the architects and the builder are Tucson natives, and they share an awe of the vast mountain ranges that ring the area. When Ibarra and Rosano saw the site the client planned to buy in a valley west of downtown, they balked. The flat piece of land would be easy to build on, but the only views it offered were those of neighboring tract houses. On their advice, the client purchased another plot of land nearby. The hillside property looks out over the Tucson, Tortolita, and Santa Catalina Mountains, plus the city itself. View lots normally command a premium price, but since this one happened to be located on a challenging incline, it cost about the same as the first property.

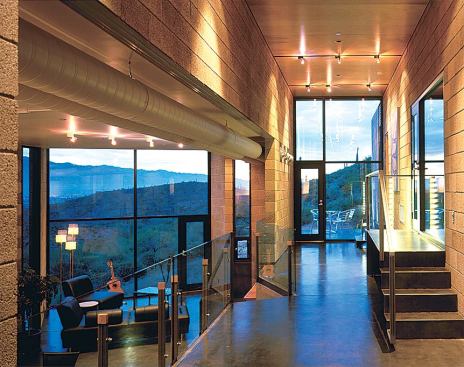

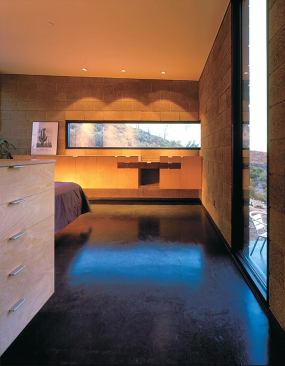

Their college professor, noted Tucson architect Judith Chafee, had taught Ibarra, Rosano, and Repp the importance of spending time on site before starting design. In this case their site research led them to a three-tiered, 2,150-square-foot plan that nestles into the hillside. “The shape of the plan follows the contours of the terrain,” says Ibarra. The first level contains the public spaces—a living and dining room open to a kitchen—and the third holds bedrooms and a courtyard. Both of these levels measure 14 feet across, a standard dimension in Presidio houses. The home’s middle layer features a zaguan, another element borrowed from the local architectural vernacular. “The zaguan was a Moorish tradition transported to Mexico,” says Rosano. “It’s an entry with a hall that takes you straight through the house and back outside.”

During spring, summer and fall, the client can leave the door at the end of the hall open, providing a path for cross-ventilating breezes that flow in through the zaguan. Ibarra and Rosano carefully located every window in the house to cross-ventilate with another, so air currents are constantly crisscrossing the spaces. They also placed punkah louvers, aluminum air distributors that harness and direct air through a space, atop the kitchen walls. A traditional courtyard on the bedroom level provides another place for fresh air to enter the house. While the home does have air conditioning (a necessity for the area’s 100-degree-plus summer days), it and the heating system are separated into two zones so the owners don’t have to heat or cool the entire house at once.

In addition to setting up cross-ventilation, the windows also serve to manipulate the home’s spatial qualities. “We broke all the corners with horizontal windows,” explains Rosano. “It eliminates the feeling of being inside a box.” They went even further to achieve that effect in the living room, rotating one corner by 45 degrees in order to capture city views.

Details: Modern Masonry

The home’s energy efficiency level received a boost from its Integra wall system. The system consists of post-tensioned concrete masonry blocks filled with polyurethane foam insulation. “It’s a fairly economic product that can be exposed inside and outside,” says Rosano. “The walls have an R-value of 26.”

The blocks are attractive, too—the architects chose to leave them uncovered on the home’s interior as well as the exterior. Manufacturer Superlite Block of Phoenix, Ariz., sells the system in nine earthy shades, and Ibarra, Rosano, and Repp are big fans. “One of the reasons I like to build with Integra block is that you get really straight walls,” says Repp. “The cabinets fit perfectly.”

Building with Integra, he says, is slightly more difficult than building with conventional masonry. The block is strengthened with threaded steel rods, rather than standard rebar. The rods don’t bear weight themselves; instead, they compress the block so it can support more mass. The system produces walls that are as strong as or stronger than regular concrete-block walls. “The tension rods make it a little harder to stabilize,” Repp says. But using Integra block doesn’t require a huge amount of extra engineering. Superlite sends a specialist to engineer the walls and lintels; other than that the architect and builder are on their own.

First-time guests might be excused if they have trouble finding the house, since its tan masonry walls and the carport’s rusted steel siding blend right into the rocky site. The project’s terraced floor plan also intensifies its relationship to its surroundings. Building the house to step up the site in this fashion wasn’t easy, for the hill consists of solid rock. Repp estimates that he cleared out 250 to 300 tons of rock before starting construction. “We doweled the foundation directly into the rock,” he says. “Solid rock has a bearing capacity of 15,000 psi. It’s stronger than any concrete footing you could ever pour. It’s the first time I’d done a foundation that way, and I’d do it every time if I could.” This method saved money, too—Repp says the cost of removing still more rock from the site to make room for footings would have been considerable. “When you’re digging in solid rock, it fractures in weird ways,” he says. “So you have to take out more rock than you need to.”

Like the builders of the Presidio houses 200 years ago, Ibarra, Rosano, and Repp chose natural materials that connect the structure to its environment. They also tried to create the loft-like atmosphere the client wanted. The Integra concrete masonry units that form the exterior and interior walls were sandblasted to give them a smoother texture. Commercial storefront windows and polished concrete floors complement the open, Modern interiors. And the concrete floors’ straightforward beauty makes them completely appropriate to the history and culture of the area. “We don’t like a lot of tiles and ‘Southwestern’ stuff,” says Ibarra. “Finding the simplest way to get somewhere is a very Tucson thing.”

Project Credits:

Builder: Repp Construction, Tucson, Ariz.; Architect: Ibarra Rosano Design Architecture, Tucson; Living space: 2,150 square feet; Site size: 2.3 acres; Construction cost: Withheld; Photographer: Bill Timmerman (except where noted).

Resources:

Appliances: GE; Bathroom faucets: Grohe; Bathroom tile: Carter Glass Mosaic; Brick masonry products: Superlite Block; Concrete pigment: Davis Colors; Kitchen sink: Elkay; Lighting fixtures: Nora Lightin; Paint: Dunn-Edwards; Punkah louvers: Air Concepts.