Nat Rea, Courtesy of Union Studio

CONCORD RIVERWALK Concord Riverwalk, selected as Community of t… CONCORD RIVERWALK Concord Riverwalk, selected as Community of the year by the NAHB, is based on a century-old idea of a bungalow community.

Nat Rea, Courtesy of Union Studio

CONCORD RIVERWALK The homes are located half a mile from the As… CONCORD RIVERWALK The homes are located half a mile from the Assabet River walk, and in the other direction, half mile from West Concord town services.

Nat Rea, Courtesy of Union Studio

CONCORD RIVERWALK Interiors are traditional, but with sightline… CONCORD RIVERWALK Interiors are traditional, but with sightlines and light traveling all through the homes.

Ross Chapin Architects in collaboration with Union Studio

CONCORD RIVERWALK The site plan encourages interaction amongst … CONCORD RIVERWALK The site plan encourages interaction amongst residents.

Shem Rose

FINNEY CROSSING Snyder Homes received no opposition from neighb… FINNEY CROSSING Snyder Homes received no opposition from neighbors or community leaders when planning the new development.

Jim Westphalen

FINNEY CROSSING Floor plans optimize privacy by limiting window… FINNEY CROSSING Floor plans optimize privacy by limiting windows that face other units and offering private entrances when possible.

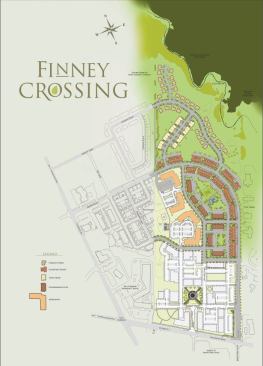

Courtesy Snyder Homes

FINNEY CROSSING The site is adjacent to open land to the north … FINNEY CROSSING The site is adjacent to open land to the north and mixed-use development such as a pharmacy, a grocery, restaurants, a movie theater, and a community college to the south.

Courtesy South Main Building Co.

SOUTH MAIN The town of Buena Vista is a walkable community on t… SOUTH MAIN The town of Buena Vista is a walkable community on the Arkansas River.

Dustin Urban

SOUTH MAIN Residences are live-work in the traditional sense, w… SOUTH MAIN Residences are live-work in the traditional sense, with flats above retail.

Kenny Craft

SOUTH MAIN Housing types vary, from old-style flats above retai… SOUTH MAIN Housing types vary, from old-style flats above retail establishments to rustic single-family townhomes.

SOUTH MAIN About 40 residential units are now complete with an … SOUTH MAIN About 40 residential units are now complete with an eventual goal of 300.

Courtesy Ranquist Development

THE BACKYARD The Backyard is in Andersonville, a vibrant Chicag… THE BACKYARD The Backyard is in Andersonville, a vibrant Chicago neighborhood with restaurants, music, and transit close by.

Patrick Warneka

The project had fallen on hard times during the downturn and was… The project had fallen on hard times during the downturn and was rescued by Ranquist Development.

Patrick Warneka

Units offer privacy while being in the midst of an urban core wi… Units offer privacy while being in the midst of an urban core with all the conveniences.

There are 23 townhomes, with backyards that range from 200 to 1,… There are 23 townhomes, with backyards that range from 200 to 1,700 square feet.

Photos: Frank Domin

Frank Domin

901 JEFFERSON As opposed to many walkable developments, Oakland… 901 JEFFERSON As opposed to many walkable developments, Oakland actually has too much retail storefront space. One of the challenges was making ground-floor residences private, light, and quiet.

901 JEFFERSON The building is unabashedly modern, but it was bu… 901 JEFFERSON The building is unabashedly modern, but it was built on the scale of the Victorian homes in the adjacent neighborhood.