This week, Japan-based home builder Daiwa House landed with a bang in United States home building, with the acquisition of mid-Atlantic states regional power Stanley Martin Homes, which ranked No. 57 in May’s Builder 100, with 2015 revenue of $418 million on closings of 713 single-family detached and attached units.

Daiwa–which teamed up in a multifamily investment deal with Lincoln Property Company in 2014–joins North America Sekisui House (NASH) and Sumitomo Forestry America as increasingly important players in North America’s residential neighborhood development arena. Daiwa’s designs on investment in the United States are for “strong emphasis on expansion” here. Sumitomo has a stated goal of 5,000 completed homes per year among its U.S. network of operators by 2018, which would effectively double the closings of its current, four-company U.S. portfolio in that time. NASH, too, has been on a growth tear with its primary U.S. partner Newland Communities.

The entry of Japanese (and other international companies) as a significant part of the mergers and acquisitions playing field during the post-mid-point in the current housing cycle may make things interesting, especially for big public builders.

Motivating Japanese home building organizations in their pursuit of beachheads here in the U.S. are two strongly related forces: a need for yield on invested capital and diminishing opportunity to produce that yield in Japan, where the population is shrinking and household formation has stagnated.

Here, with astute capital investment, the three Japanese organizations can unleash growth they’re looking for by teaming up with strong operators whose main constraint to faster-growth through this point in the housing recovery cycle has been access to financial resources to buy more land.

Meanwhile, strong, well-regarded, entrepreneurially-focused principal leaders of the U.S. operations get to stay in place in the near-term horizon with companies each of them built from the get-go, essentially executing on their playbook with an operating and financial partner. What the U.S. operators we’ve talked to say is that working with their Japanese organization partners reveals powerful affinities around customer-care, operational efficiencies, respectful communication, and a blend of strategic autonomy and transparency.

The issue here is this. When Sumitomo reaches its 2018 goal of closing 5,000 homes in the United States, it would effectively become a top 20 home builder here. Daiwa House’s entry, and its intentions to invest aggressively in this market, may scale to an equally strong presence in America.

We’re fascinated by the notion that if Japanese-owned enterprises are doing 10,000 homes and tying up, say, 50,000 lots, how does that impact public home builders need for volume growth during the same time period.

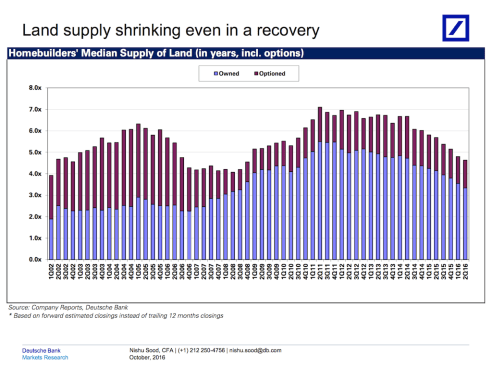

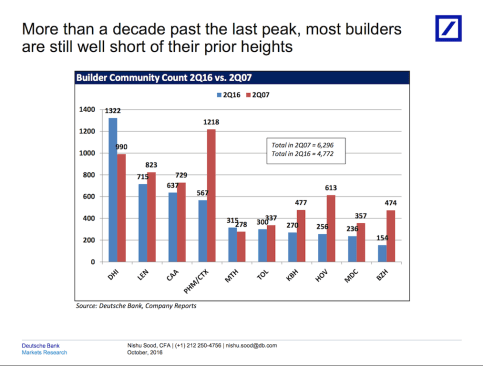

We know, from this terrific analysis from Deutsche Bank home building senior analyst Nishu Sood, that public builders need–despite signs that the current recovery may have past its growth peak–to restock their land pipelines, and drive harder into lower-priced home and community offerings. Here, Sood shows that public builders’ lot inventories in years’ supply have been drifting lower even as starts and new home sales trends have been positive.

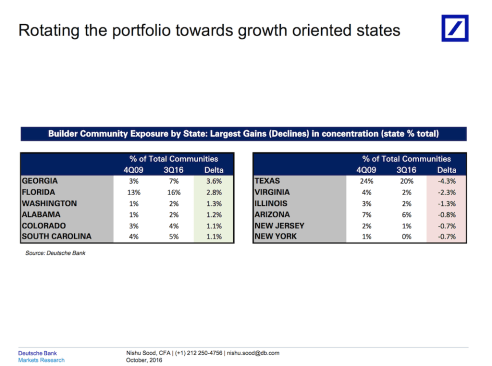

What’s more, Sood finds that big home builders are increasingly concentrating their operational footprints in fewer, better-scaled, higher-growth markets–Atlanta, for example–in an attempt to power both inventory turns and SG&A controls, even as they focus on entry level, and entry-level plus customer segments. Here’s a look, from Nishu, at how the publics are “rotating” out of markets where operational efficiencies were hard to come by into the power markets, with strong economic fundamentals, job formations, wage growth, and household formation.

So, for private home builders there’s a growing predicament that boils down to a wager on what’s going to transpire between now and, say 2025.

If there’s expectations that, despite demographic waves in favor of growth, there may be a downturn within the next three to five years, there’d be a motivation to sell while valuations are still high and climbing and acquirer appetite for select assets, geographies, and operators is keen.

At the same time, as Sood’s analysis shows, the publics have been slow to pull the trigger and show their hand on aggressive land investment, except in a few market arenas, so it’s not a sure-bet for a private builder to go on the block and expect multiple bids to drive their price up.

However, with two Japanese organizations–and other international players also seeking safe-haven residential real estate plays in the United States–as new bidders in the mix, it may serve to stir the pot on public-private merger and acquisition activity in the months ahead. Heaven knows, Wall Street is loving the deals right now, so it won’t be a surprise to see a few more home builder M&A transactions before yearend.