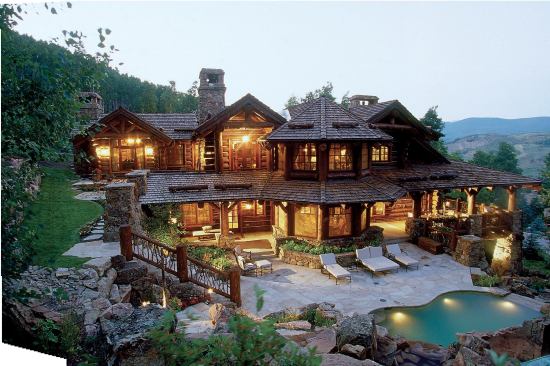

Equally impressive are the mechanical systems that support the compound. A 1,200-square-foot utility room in the main building houses two gas boilers the size of minivans, with 30-inch-diameter exhaust mufflers. “One’s 4 million BTU, the other is 2.5,” Brubaker says. A geothermal heat pump system serves mostly for air conditioning, although it will keep the house above freezing when it is unoccupied (after all, this is a vacation home). An adjoining room houses perhaps two dozen main electrical panels.

A third room, with its own air conditioning system, holds rack upon rack of A/V equipment and banks of low-voltage lighting panels. The 5-foot-high, 7,000-square-foot crawl space is also crowded with pipes and mechanical equipment. “We’ve got 39 heat pumps around the house,” Brubaker says.

Two 20,000-gallon water tanks ensure sufficient pressure for the sprinkler system and domestic use. A third 10,000-gallon tank offsets evaporation from the outdoor pool. Hydronic radiant heating keeps the 14,000 square feet of sandstone patio and pool deck clear of snow. To reach the remote building site, the company trenched a 2-mile line of 4,000-amp, three-phase power. “We ran about a mile-and-a-half gas line in here,” Brubaker adds. The line is 8 inches in diameter.

Producing a house of this scale, technical complexity, and architectural detail requires a small army of workers-at Christmas time, Brubaker reports, “The owners bought 160 little presents and had them shipped out here”-but only a handful have been Beck employees. The company concentrates its resources at the top, assigning project managers only two or three projects at a time. Most projects get a full-time site superintendent; larger ones might get a foreman as well. This one had two project managers and two superintendents, plus a clerk to surf the paperwork. With the exception of its Customer Care division, which handles warranty work, inspections, and maintenance for previous clients, the company subcontracts virtually all its hands-on labor.

Beck says that one of his company’s greatest resources is its roster of trusted trade contractors, and even the sharpest eye would have a job finding fault with the results. Getting top-quality finish work may be easier with subcontractors than with payroll employees, Beck says, “because you’re not invested in the relationship in the same way.” With subcontractors, the company can present its standards explicitly, up front. On the rare occasion when a subcontractor fails to live up to expectations or bites off more than he can chew, the company can call the bullpen and bring in a reliever.

As that picture on Beck’s office wall attests, though, the system has been sometime in the making. When he sat for that portrait, Beck was still relatively new to this valley. Recently returned from an extended combat tour in Vietnam, he had left his native Wisconsin to ski the Rockies, taking carpentry jobs only to fill the warmer months. But construction suited him, and he signed up for an apprenticeship program sponsored by the local carpenter’s union.

After a couple of years on the crew of a good custom builder, he struck out on his own. One of his first hires was another ski instructor, Frank Payne. It was a good move. Payne has stuck with Beck for 34 years as carpenter, superintendent, project manager, vice president, and now president. In their early years, Beck says, “we tried all kinds of stuff.” The custom residential market had not yet taken off, so they took whatever work came their way: a police department remodel, a school water system, residential remodels, and light commercial jobs, “all these fun things that we didn’t know how to do, but we’d have to find out.”

Even then, though, Beck and Payne had a sense of what they were working toward. “We felt like we were the first work-all-year professional guys,” Beck says. “We realized there would be a place for a very organized, professional, full-time company.” And after starting out doing everything from foundations to carpentry to roofing to drywall, Beck decided they could serve their clients better by concentrating their efforts higher up on the organizational chart. “We were better at managing that stuff than doing it,” he says, “so that’s where we put our emphasis.”

Beck’s military experience provided the management model. “I was in the Green Berets, Special Forces,” Beck says. As an officer, Beck led a team of highly trained soldiers with very specialized skills. “Weapons specialists, camo specialists … I realized that these guys knew more than I did, and, while I was in charge, I had to engage their skills. I had to engage them in such a way as to get them to believe in what we were doing.”

Beck emerged from the service with a non-dogmatic, collaborative leadership style, “more of a servant-leadership thing,” he says. “It was hands-on, but we did executive work. It turns out it was a great translation to working with subcontractors and carpenters. You set high standards, but you let them know your expectations early on.”

Subcontracting the field work has allowed the firm to focus on its management systems and build a formidable crew of superintendents and project managers. The latter-16 superintendents and 11 project managers-average more than seven years of tenure. Brubaker, now 48, hired on 25 years ago.

The company’s other vice president, Kevin O’Donnell, who focuses on marketing and business development as well as project management, has only 12 years under his belt and considers himself “a newbie.” The company has made an art of pairing superintendents and project managers with complementary personalities and skill sets, and it allows on-site management teams a significant degree of autonomy. But it has also achieved something of a group mind-meld, which is reflected in its superintendent field manual. A continuous work in progress, the manual represents the combined knowledge ofthe entire team.

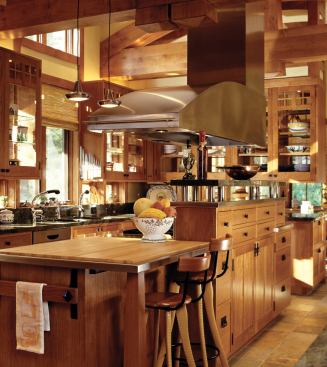

Hefting the 400-page slab, Payne says, “This is a sequential document, from dirt work to foundation to framing, and so on.” Entries range from nuts-and-bolts matters (don’t accept spruce-fir framing lumber when the spec calls for Douglas fir) to material-selection advice (no limestone counters in the kitchen) and such arcana as the fact that dogs tend to dislike in-floor radiant heat.

The construction-checklist section runs to 39 pages. At their monthly meetings, the project managers and superintendents continuously update the manual (which Payne has actually copyrighted), sometimes with the help of an outside expert invited to speak on a new product or process.

The company’s emphasis on learning and self examination verges on obsession. Beck contracts with an outside company called Priority Management, which provides a time-management training course. “Everybody in the company goes through that,” he says. “It’s an automatic. When guys have to manage all this construction and do paperwork too, you’ve got to give them tools.”

A few years back, Beck sent Brubaker and O’Donnell to Florida for a week-long course of management training. The company produces an “after action report” on every project. “We grade our subcontractors,” Becksays, “we grade ourselves. What worked, what didn’t? It’s layers of always checking in with everybody.” To hone the energy performance of the company’s buildings, the company brought in Minneapolis building science specialist Mark LaLiberte to lecture on the topic. “We invited our local architects, too,” Beck says, “to get them to buy in.”

This self-improvement imperative goes all the way to the top. More than a decade ago, Beck and Payne realized that the company had outgrown the seat-of-the-pants business skills that had served them up to that point. So they sent themselves back to school, taking a series of week-long management classes at the University of Wisconsin. “We’re businessmen in the construction business,” Beck says. “But,” Payne adds, “we weren’t always.” Beck nods. “We had to make that transition inorder to survive.” In fact, he says, “We’ve reinvented ourselves several times as we’ve gotten bigger or changed the kind of work we were doing.”

And Beck has not been shy about enlisting the help of outside consultants. Some 10 years ago, the construction-industry consulting firm FMI conducted a thorough analysis and revision of the company’s systems and procedures.

But the latest reinvention will be the most significant since Beck founded the company, because when this one is complete, Beck will no longer run it. The process began some 15 years ago, when Beck was working on his estate plan. His insurance company referred him to John Brown, a Denver attorney and expert in “exit planning.” Brown said, in effect, “So you expect to die some day. What would you like to do before that happens?” The timing was fortuitous, because a successful exit-that is, one that allows an owner to realize a return on his investment while leaving the business in sound shape-can easily take a decade to plan and execute. The culmination is one of three scenarios: a transfer of ownership to a family member, a sale to an outside party, or a sale to company employees. Each case poses a significant challenge for the business, which must maintain operational momentum, produce a profit for its new owner, and, ineffect, fund the founder’s retirement. With that in mind, Beck put his company on a decade-long training regimen aimed at building core staff, clarifying and standardizing management systems, and maximizing profitability.

The primary goal of any exit plan is to build and preserve the value of the company. In custom building, a business with relatively few fixed assets, that value lies in people. Preparing for a successful transition, therefore, entails finding the right people and binding them to the company.

“As much as 15 years ago,” Beck says, “the question was, how are you going to compensate key individuals beyond their salary?” He began by making Payne a minority owner and offering a generous deferred compensation plan to his other key people, giving them a financial stake in the company’s success. He worked at standardizing the company’s systems and documenting its procedures, in effect downloading the management software from his own head and publishing it for the team that would take over for him. At this point in the evolution of a company, Beck says, the owner’s focus “goes from being entrepreneurial to being organizational.” Whatever role the owner has played, “You have to define that, share it, and assign it. As soon as you have a process in place, you’ve got to paper it.”