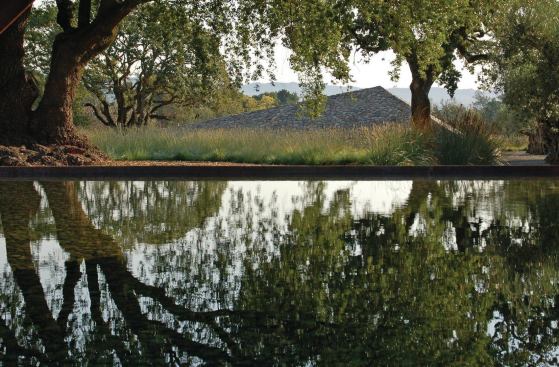

Courtesy Andrea Cochran Landscape Architecture

Andrea Cochran puts the architecture in landscape architecture. Drawing on modernist design, environmental art, and the classic French formal garden, the San Francisco–based landscape architect’s geometrically disciplined compositions deftly manipulate our perceptions of space and material while also creating practical, pleasurable outdoor rooms. We spoke with Cochran about her unique talent for extending architecture into the landscape and about running a successful design-focused firm in challenging times.

Your work has a very architectural quality. What led you to that approach?

When I was at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, I took a lot of studios with architects. We worked collaboratively on projects, and I came to realize that architects had a much more rigorous design approach than landscape architects. That colored my own approach to design, made it more a little more rigorous, and more architectural perhaps. After I graduated, some of my early jobs were with architecture firms where I was one of the in-house landscape architects. I worked for Josep Lluis Sert, who had headed the Harvard School of Design for many years (his close friend was the sculptor Joan Miro). That was quite an influence.

What kept you on the landscape side of the fence?

As a landscape architect, you are a generalist. You know a little bit about soil science; you know a lot about grading, but you’re not an engineer; you know about design, but not with the rigorous training that architects get; you know about plants, but you’re not a horticulturist. I think that’s great because we live in a complex world, where issues are not solved by just one discipline. Having that broad training allows you to lead interdisciplinary teams. You’re the one with the whole picture.

How would you describe your use of plant material?

When I design a garden, I think about making space outside. We have walls, grading, and other structural elements to create and reinforce space, but plant material is a strong shaper of space, especially at large scales. For example, planting with only a single species, like a hedge or a mass of grasses, can strongly define space. Structuring space with plants is like drawing the perimeter with a pencil and then lightly erasing the line; you create a more diaphanous edge but still retain the strength of the space. In general I’m not interested in the ornamentation of space, but rather in the strength of the space itself, using it as a vessel to highlight changes in light and the seasons.

What does your work have to say about the relationship of people to the natural world?

The landscapes that most appeal to me are at the intersection between the man-made and the natural: a farm carved into the side of a hill, the rigor of fields and orchards with hills beyond. But residential projects also involve dialogue with the owners about how they see themselves living in the landscape. Is this a contemplative space or a place for children to play? Are they going to entertain? Do they need space to grow vegetables?

How did the recession affect your business?

We did not experience a huge decline in our business during the height of the recession. I think the fact that our book [Andrea Cochran: Landscapes, Princeton Architectural Press] came out in 2009 gave us a boost that helped ease the effects. We also had a couple of larger projects that started pre-recession and were ongoing, which also helped. In terms of the market as a whole, I think there is a huge difference in California from two years ago. Home prices seem to be moving closer to pre-recession levels. Many of our clients are younger and have never built a house before, so there’s a learning curve regarding design and construction.

How do you nurture talent in your firm?

Our model is to allow younger staffers to work as a project manager on a smaller residential project while also working under a seasoned project manager on larger projects. This allows them to be mentored while also being responsible for overseeing a less complicated garden. People coming out of school now have good design skills and great computer skills. But understanding the nuances of scale is not something most people grasp at that point in their careers. It takes experience to understand how a space will feel and what is too big or too small. They also need to work on having a good knowledge of plant materials and how plants do in different environments. Those are fine distinctions that actually make a difference.

Is there a type of project you haven’t tried but would like to?

Right now the California drought is such a big issue that it would be timely and educational to do a landscape that tells the story of water: how it’s used and preserved, how precious it is. I was just in Oaxaca, Mexico, where there are huge cisterns built under the terraces and plazas. At the Ethnobotanical Gardens there, the water meanders in a thin runnel through the garden recharging the cistern. We don’t value water in that way here—it’s so inexpensive that we don’t really think about how precious it is.