Panoramic Locations

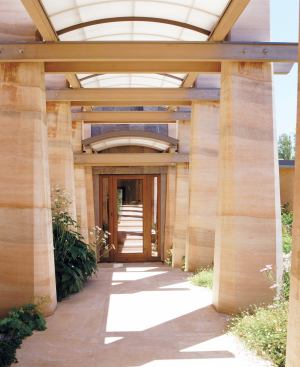

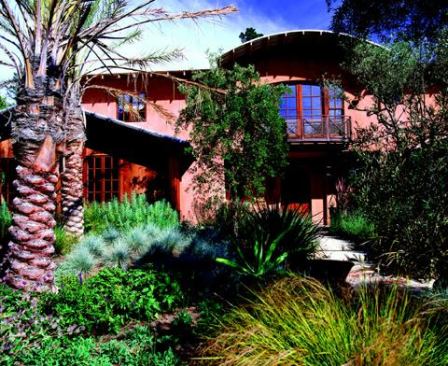

Combining sprayed earth exterior walls and rammed earth columns,…

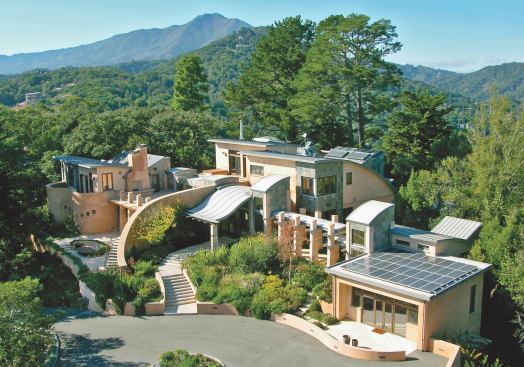

How green can a house like this be? Very green. For one thing, Warner says, “Very few woods are used, except the wood on the floor, which is FSC-certified maple.” If you hiked the hills that rise above the house, you would see the rooftop photovoltaic array that will produce most of the energy the building will consume. The exterior will never need paint, and the interior materials and finishes will not off-gas unhealthy compounds. The clients wanted a building-as-machine Modernist house, and that’s what they got, but with Warner as their builder, they got much more than that. “The owners didn’t realize it, but we made them go green,” Warner says, laughing again. “And it was seamless. You can be green in any style.”

Where this house stands out, however, is in its relationship to its site. The stream that it bridges is the Corte Madera Creek, which, Warner explains, “has one of the last runs of salmon in the Bay area.” Getting a project like this permitted, much less built, takes someone who has not only studied the regulations, but understands the science behind them. “A lot of what I do is on entitlement processes,” Warner says, using the term of art for nailing down what a property owner will be allowed to do. California’s environmental regulations have made that job vastly more involved “than 10 years ago, or even five years ago,” he says. “On one ranch project we had 42 permits from different agencies,” from the California Coastal Commission to the Department of Fish and Game to the Army Corps of Engineers to the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. A current project at the base of a steep 200-foot bank on the shore of the San Francisco Bay presented, shall we say, access challenges. “On the big steel pieces,” Warner says, “we had a helicopter drop,” which required coordination with the Coast Guard. Projects like that in times like these, he says, have made permitting a specialty unto itself. “It’s becoming too complicated even for architects.” But Warner is not complaining; the approvals process is a briar patch where he feels completely at home.

That may be because Warner views environmental regulations as more than pointless hassles. In fact, as he warms to the subject he begins to sound less like a builder and more like a biology teacher. Stream corridors like the one that runs down the center of this property, he says, are vital pathways for a whole community of animals: salmon, deer, the wood rats that thrive at the rural/suburban fringe and are the sole food source for the endangered spotted owl. No stream, no rats, no owls. “These are some of the ripple effects,” he explains. “People don’t realize the importance of keeping these corridors open.” By bridging the creek—70 feet of its length is over open air—this house leaves the way open for even the largest mammals in the area. As if on cue, a single deer picks its way under the house and warily past the Redhorse crew gathered outside on lunch break. “Proof of concept,” says Warner. “The site is precious, and you have to build with a high level of execution. And if you build with a high level of execution, it will remain precious.”

Unlike many builders who have gone green in recent years, Warner experienced no conversion process; he was green before he became a builder. Still, and to his credit, he does not preach doom on the subject. He is minutely aware of the consequences of building-as-usual: resource depletion, environmental degradation, climate change. He views a transition to green building as an imperative rather than an option. But coming from Warner, that prospect sounds energizing rather than frightening. He emphasizes the direct benefits of this approach—a comfortable, healthy indoor environment; long-term structural durability; mechanical systems that pay for themselves in energy savings; life-cycle costs substantially lower than for conventional buildings—without moralizing. “I never started out being an ideologue, saying, ‘I can’t work with you unless you do it this way.’” His credo is simple, positive, and sustainable in itself: “Whenever possible, go green. Any level is a victory.” Focusing always on the attainable, Redhorse first scaled the lower slopes of that green mountain, Warner says, “then got to base camp, then got to summit.”

Starting out in the Bay area, where Warner grew up, didn’t hurt. Redhorse’s geographical range, from the Napa and Sonoma valleys north of San Francisco to the Palo Alto area to the south, has more than its share of spectacular sites. Its population also represents one of the world’s great concentrations of wealth, advanced education, entrepreneurial energy, and environmental awareness. Warner’s market lies at the point where these phenomena overlap. “We have a very diverse clientele,” he says, “all industries and all age groups. We have clients in their 80s starting a new home, and we have young clients in their 30s and late 20s.” The most important common traits among them are creativity and interest in trying new things. “Some of my best clients”—business owners, inventors, musicians—“are ones who are kind of pushing the envelope.” One, he says, “invented a little gizmo called the Palm Pilot.”