Panoramic Locations

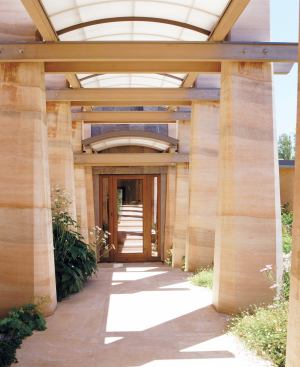

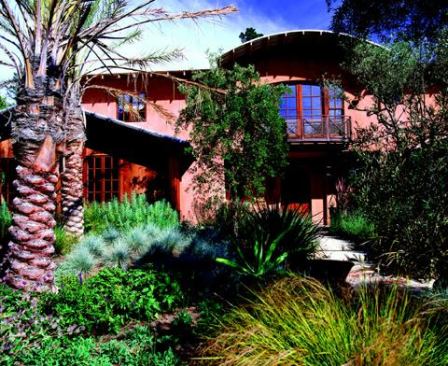

Combining sprayed earth exterior walls and rammed earth columns,…

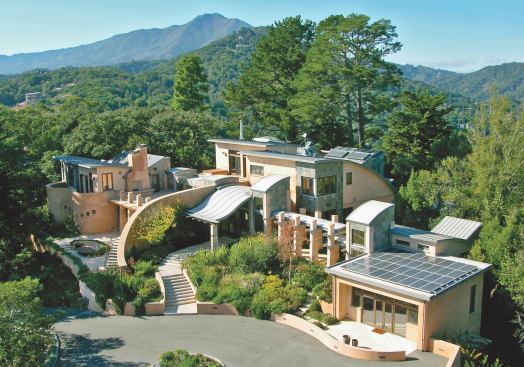

Warner is not free to disclose who owns the next house we visit, but it provides a perfect case in point. The road from the property’s keypad-operated gate winds for three-quarters of a mile, through groves of live oak and eucalyptus, crossing two bridges over deep ravines, and climbing to a ridge with commanding views of the valley floor below. The owner bought 300 acres that abut a 1,800-acre preserve, keeping 20 for his home site and donating the rest as public open space. The house, dug into the shoulder of the hill, encloses 8,000 square feet of living space. Site superintendent Scott Vreeland, a fit, energetic man in his mid-40s, meets us in the parking area above the house, a vantage point from which the building appears as a series of wavelike copper roofs emerging from the hillside. Stone steps descend to a terrace and pool at the entry level, where we can see the other side of that roof: undulating laminated fir beams, up to 18 inches by 8½ inches in section and up to 60 feet long, supported on columns of stripped and varnished Douglas fir logs that range from 10 feet to more than 25 feet in height. This house is all about wood, and there is not a drop of paint to be seen anywhere. The exterior walls are salvaged redwood. The custom windows are FSC-certified mahogany on the outside and domestic cherry on the inside. Every square inch of interior wall is paneled in horizontal tongue-and-groove cherry boards. And, as Vreeland proudly points out, the paneling layout is consistent throughout. You could pick two horizontal joints at the furthest ends of the house and count only whole boards between them. “This was a mathematical equation all the way through,” he says.

Here are some more numbers: The foundation includes retaining walls up to 27 feet high, reinforced (this being earthquake country) with two vertical layers of No. 8 rebar at 3 inches on center. “We had to use special plasticizers in the concrete to get it to flow around that much steel,” Vreeland says. The longest roof beam bears on “five vertical hit spots, and three of them are visible, and one of them is on the stone wall. At 17-cents-a-second crane time, it had to hit right the first time.” For the 17 fir columns, the company located a supply of north-slope trees whose slow growth yields a less tapered, more stable log than those grown on sunny south-facing slopes (“I can guarantee you that was not a spec,” Warner says). To seal the stripped logs, Vreeland says, “We built dip tanks and dropped them in and rolled them around,” first in a borax solution, to kill mold spores, then in an environmentally friendly spar varnish. Out of sight up the hill are two large, ground-mounted photovoltaic arrays and a bank of solar hot-water panels, 17 300-foot geothermal bores, and a 12,000-gallon concrete water storage tank that ensures adequate water pressure and a margin of safety in case of fire. The client himself designed the computerized controls for the house’s advanced mechanical systems. Sensors mounted in every room monitor the building’s climate “to the point where he knows the efficiency of the systems,” Warner says, and can optimize them remotely over the Internet.

Touring the house has taken us into dinner time, but Vreeland is in no hurry to leave. He has spent the last three years of his life on this project, and he is clearly savoring the last few days before he hands over the keys. He has worked with Warner for more than 25 years—they used to train for triathlons together—and the two talk comfortably about what comes next. Noting the exterior’s “boat-level finish,” Warner says he has already spoken with the owners about an inspection and maintenance schedule. As we take in the view across the valley from the house’s rooftop observation deck (complete with a weather-tight compartment for telescope storage), neither man is taking the least bit for granted what they have accomplished here. And they are in full agreement about what it takes to make something like this happen. “You never snivel, and there is no stop,” Warner says, quoting what has become a company motto. The same standard applies to everyone on the job, from laborers on up: “They don’t show up on the job unless they’re in for perfection,” he says. Vreeland nods, “If it’s not right, it’s wrong.” You can see it in the attitudes of the subcontractors on Redhorse jobs. Like Harvard freshmen, they realize that not everyone gets the chance to perform at this level; they seem to view it as a privilege.

None of them more than Warner, though, who seems so continuously charged by his job that such necessities as eating (by now we’re at the far side of dinner time) and sleeping might seem superfluous. Aside from his family—Warner is married, with two sons—one of the few things that compete for his attention is cycling, for which he harbors a lifelong passion. The bicycle, 100 percent energy efficient and environmentally friendly, seems an appropriate vehicle for a green builder. But if you envision Warner on a three-speed, hauling groceries from the food co-op, your imagination is running in the wrong direction. Warner likes to ride fast—he’s spun a wheel socially with Lance Armstrong’s coach—and he loves high-tech gear. His current ride is a carbon fiber road bike that weighs less than 15 pounds. Bikes don’t get a lot lighter than that, and this one does it by replacing metal parts with those made of featherweight carbon-fiber-reinforced plastic. Warner likens the advanced technology involved in the bike he rides to the houses that his company builds. He especially likes the Modernist houses, which must pack a full complement of advanced technology into an attenuated structural envelope. “You don’t have copious amounts of space to drive things through, big attics and big soffits,” Warner says. Instead, “You drive all the shop drawings and you drive all the systems analysis of what you choose very hard. It’s like a bike. You want to ride the carbon, and some of these houses are riding carbon.”