Robert Reck

Dubbed 3300 by its builder, this 30,000 square foot building hou…

Cruising Speed

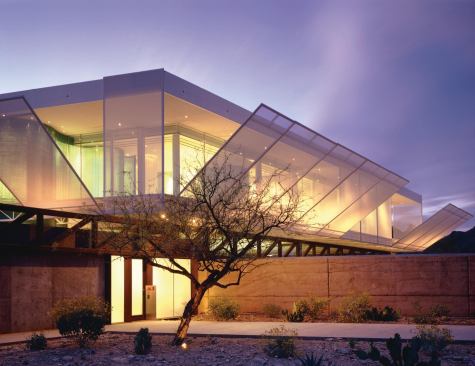

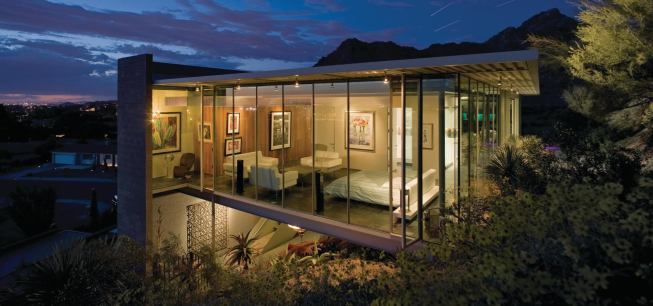

The firm’s capabilities are amply on display in a house designed by Wendell Burnette Architects, now under construction in a gated community in Scottsdale, Ariz. Approaching the gate on a sun-drenched fall day, Byrnes pulls his Land Rover around a line of two dozen tradesman’s trucks waiting to enter. “This is the first time I’ve seen a line here in two years,” he remarks. “It used to be a mile.” Inside the gate, one finds what one expects—large Southwest-style houses—and something rather unexpected: a low, abstractly geometrical form with crisp, planar surfaces rendered in rammed earth and Cor-Ten steel. Virtually windowless at its entry side, the house expands as the grade falls away, cracking its obscure shell to reveal broad walls of glass that bound a private, multilevel courtyard.

The house is large—nearly 8,000 square feet—but that number is made practically moot by the audacity of the design and by a combination of technology, material, and craft utterly unique in the residential sphere. The massive rammed earth walls are pierced here and there by pyramidal or conical openings that required CZ to break new ground in formwork. The main-level ceilings are plates of 16-gauge hot-rolled steel fastened with superstrong adhesive tape, except for those that conceal important equipment, which are held in place by magnets. The master bath is lined—floors and walls—with sheets of onyx “grouted” with bronze strips. One outside wall—18 feet wide by 12 feet tall, mounted with bronze shower fittings, and bisected by a full-width glass panel—hinges open into a private courtyard for al fresco showers.

Large pieces of building that move in similarly unlikely and elegant ways are a recurring theme. The main entry door is a ceiling-height panel of Starfire low-iron glass. “Nine feet by 11 1/2 feet,” Byrnes says. “An $18,000 piece of glass.” In the living area, a glass wall rises 13 feet from the ground-concrete floor to the steel-paneled ceiling, four of its 5-foot-wide panels pivoting like vertical louvers to open the room to the courtyard. “This house has been completely handmade by Construction Zone,” Byrnes notes, including the glazing assemblies that are so integral to its character (see sidebar “Clear Advantage,” at left). “We’ve done more drawing on this project—times two—than we’ve done on all our other projects combined for 20 years. That kind of separates us from other builders. We draw and draw and draw and engineer and engineer and engineer.” And build: “We’re at six and a half years in construction, and probably about two more years in design. We had 40 to 50 people of my staff out here full time for years.”

The project was a godsend during years when the pipeline of work slowed to a trickle, and when projects in hand could turn to dust overnight. To provide a glimpse at the latter scenario, Byrnes heads toward a would-be trophy home in another upscale subdivision. Ringed by chain link fence and open to the elements, the house stands on a construction site idled when the client put the $25 million project on indefinite hold halfway to completion. Designed by Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, the house looks like an abandoned airport terminal. “We’ve been stuck in the mud here for about three years,” says Byrnes, descending the dirt ramp to a 5,000-square-foot subterranean garage. Inside the cavernous space, two CZ workers are fabricating steel-frame glazing units for another project. The company is using the building as overflow shop space while it house-sits the property for the owner. Byrnes isn’t out significant money on the job, but it still visibly pains him to be here. A compulsively organized person—he uses a straightedge to letter his to-do list—Byrnes lives to complete things. And this big, unavoidable thing stubbornly resists completion.

Interstate System

What is most striking about the visit, though, is not what a hard blow the housing crash dealt, but how quickly and creatively Byrnes rebounded. Recognizing two of his company’s key assets—a young, talented, flexible staff and close ties to architects with nationwide clientele—he began to accept projects he previously would have rejected as too distant. Once untethered from his home base, Byrnes identified a wealth of opportunities. An earlier Phoenix house CZ built for San Antonio–based Lake|Flato Architects set the stage for projects with that firm in Mississippi, South Dakota, California, and Texas. Out-of-state work for other architects followed, along with CZ-designed remote-site work. “Right now, we have three jobs under construction in Arizona,” Byrnes says, “and five out of state.”

Project manager Matthew Muller, 35 and a licensed architect, is just back from a Lake|Flato project in South Dakota. He visits every two to three weeks to huddle with the company’s project superintendent, who will stay on site for the duration (Byrnes visits the company’s remote projects as needed). For the South Dakota job, CZ imported a few specialized Phoenix subcontractors and a mason from Texas, Muller says, “but everything else has been local guys.” The model works well in remote, rural areas, where local general contractors often lack experience coordinating complex, technically sophisticated projects. What CZ offers in such situations is management expertise and an architectural eye on the job. And because local builders tend to charge an “afraid to do it” premium for one-off modern houses, CZ often is the cost-effective solution.

Ted Flato was the partner in charge on his firm’s first CZ project, in Phoenix. “It was a remote location for us,” Flato says, “so we were hoping to find someone who understands our kind of modernism, the window details and door details.” Byrnes and the CZ crew seemed capable of reading his mind. “We do a very thorough set of drawings,” Flato says, “but there are always some details that you’d never get to.” CZ filled in the blanks, Flato says, “and made choices that were not only great, but also were completely in the spirit of what we were doing. They were as good as or better than what we would have done. It was like having someone from my office on the jobsite all the time.” Flato invited Byrnes to work in Texas, but there was too much action in Phoenix. Until, of course, there wasn’t. While Flato and his firm sympathized, he says, “we also said that this is a real opportunity, so we brought Andy into some other projects in Texas. We knew he would get it.”

The South Dakota project “is a huge challenge because it’s not an area that’s used to doing custom homes,” Flato says. “People are not even used to looking at drawings that have a lot of specificity. Andy actually knows what we do and can say, ‘Well, I can build it for X.’ He was game to go there and also to leverage some of the talent that’s up there. It allowed us to get some good architecture for good value. It’s not that he cuts corners, he just knows how to make this stuff.”