John Noltner Photography

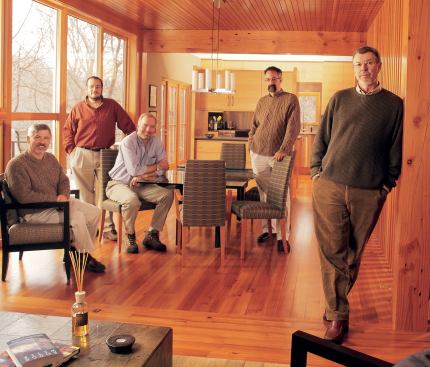

Choice Wood's brain trust — partners (from left) Mark McClellan…

It’s Tuesday morning, and Nick Smaby’s house is ready for its closeup. The Sheetrock is finished, the narrow-strip, quartersawn oak flooring has been laid and urethaned, the cabinet boxes set. The tile man is working in the master bath. The granite subcontractor has templated for kitchen counters. And in the master bedroom a young woman in clean work clothes is talking to a video camera. “The material is an engineered wood-grained plastic, 6 mils thick,” she explains earnestly, “and Nick has chosen a teak-like finish …” In a couple of weeks the house will appear on Hometime, a building-and-remodeling show that broadcasts on public television nationwide. That’s a big deal for the product reps milling about in the living room—the show will bring valuable exposure—but the builder takes it in stride. “We have a long-standing relationship with Hometime,” says Smaby, whose Choice Wood Company first saw its work televised on the show a dozen years ago. Back then, Smaby regularly appeared on screen, an experience that opened his eyes to the reach of construction TV. “I’d go to a meeting,” he says, “and people would look at me and say, ‘God, you look familiar.’” They should have kept him on the show. A fit and rugged 59, Midwest modest but Ivy League articulate, Smaby fits the role better than any television builder we’ve seen.

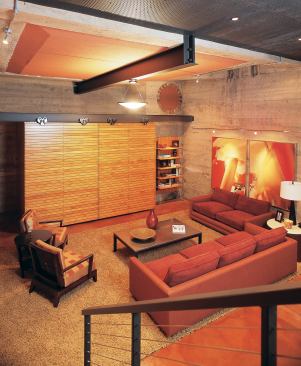

Today, though, the star is the house, a mid-century Modern that Smaby is remodeling as an empty nest for his wife and himself. It makes an apt subject. In addition to the surfacing material that actress found so interesting—with which the manufacturer is said to have wrapped an entire office building, and which here makes a wall of laminate cabinets look almost unsettlingly like hardwood—the project includes a slick pre-fabricated aluminum screened-porch system, an entrance addition sided in copper, a floating cork floor over the lower-level slab, and some very clever not-so-big space planning. “We will use every square inch of the house,” Smaby says, “which is appealing to me.” Having followed Choice Wood for more than a decade, we are impressed but not surprised. Thoughtful design and a craftsman-like build are hallmarks of the company’s work. But after spending a few days on location with this custom builder, we are convinced that reality TV is missing a better subject: not just Smaby, but the company itself.

In the fine in-town neighborhoods and high-end suburbs of Minneapolis, Choice Wood is the custom builder and remodeler that everyone knows. Its architecture division’s work rivals that of the city’s best residential architects. Yet the company remains a favorite with those same architects for its cult-like devotion to craftsmanship and almost courtly approach to customer service. Behind its 40-strong crew of carpenters stands an in-house cabinet and millwork operation that is the equal of any freestanding custom shop. Ever on the lookout for new opportunities to leverage its capabilities, reputation, and customer base, the company recently launched its own real estate agency. There are plenty of sub-plots here for a full season of programming. And while company president Smaby is the lead man, he has a superb supporting cast: four partners, with whom he has built one of the most unusual and successful teams in the custom building industry.

First, a bit of back story. Choice Wood was founded in the early 1980s by five different partners (including newly minted architects Sarah Susanka, later famous for her Not So Big House books, and Dale Mulfinger, now a principal at SALA Architects in Minneapolis). That original partnership was short-lived, but it lasted long enough for Smaby, who hired on in 1983. “I was the first employee, and I was essentially hired as a carpentry foreman.” Then 37, he had already practiced law, tried writing for a while, and run a bookstore/art gallery. He had drifted into building when a friend needed some help building his own house and found that the work agreed with him. “I discovered that I had a steady hand and a good eye,” Smaby says. “And at the end of the day I could stand back and look at what I’d accomplished and feel satisfied.” When he happened upon Choice Wood—an early experiment in design/build construction—he liked that too. Almost immediately, he began lobbying for an equity stake, which sounds more impressive than it may have looked at the time. “We lost $25,000 on our first job, so partnerships were easy to come by,” Smaby deadpans. “It became apparent very early on that we didn’t know how to do this. We were short on business skills, short on building skills. The architects were pretty raw at that point. It was a wild ride for a while.” Soon after coming on board, though, Smaby made the first of a series of moves that, in time, would thoroughly reshape the company.

“Chris Jordan was a friend of mine,” he says, “and I thought that he would be an asset.” Jordan, a classically trained musician and experienced carpenter who had been working for an insurance-repair company and playing restaurant gigs at night, was at a crossroads of his own. “I was tired of pulling wet Sheetrock off of ceilings,” he remembers. Fame in the musical field did not look imminent. “I ran into Nick in a restaurant, and he said, ‘You’ve got to check this out.’” Within a year, Jordan too had bought into the business, and as the original partners moved on to other pursuits, the company gradually fell into the hands of its second-generation owners. And they had their hands full. “We did get work,” says Smaby, who was then doing all the sales, and the projects were turning out beautifully. “But we had no business person involved.” Insurance, taxes, unemployment, and other indoor matters “got pushed way to the back,” he says, shaking his head. “And we made a mess.”

Enter an unsuspecting Mark McClellan. A former banker and restaurant entrepreneur, McClellan was coming off the sale of his successful pizzeria business. Burned out and looking for a breather before deciding his next career move, he thought Smaby might have a spot for him, as a truck driver, maybe, or a carpenter’s helper. “I don’t care what you’re going to pay me,” he said; the main thing was, “I want to make no decisions.” Smaby wanted McClellan in the company, all right. But, given the man’s skill set, he was not about to hand him a shovel. “I knew that the missing piece in our business model was the business piece,” Smaby says. “We had some talent assembled at that point, and we had a good reputation. What we really needed was someone to bring some order to our business.” Setting aside his dream of manual labor, McClellan sized up the company and quickly reached a similar conclusion. “They had a great reputation, they were doing all these phenomenal projects, but no one was watching the store. Nick just did not have the time to do it. He was out there making rain.” In short order, the company had gained a third partner and, as Smaby says, “We were off to the races.”

In the clipped sentences of a man who doesn’t like to waste time, McClellan, 53, describes the fiscal house-cleaning that followed. “I did what I did best, look at things from a numbers perspective: ‘Hey, we’re not getting the discounts from our lumberyards.’All of a sudden, we’re saving $40,000 a year on our discounts. ‘Why are we renting from this slumlord guy?’ We got out of our leases with him and we bought our first building.” McClellan updated the company with a computer network and accounting software, established relationships with banks—“We had no credit lines whatsoever,” he says—shopped for better deals on insurance, and set up an unusually generous 401(k) plan (the company contributes 4 percent of wages, whether the employee contributes or not, and typically kicks in another 1 percent at the end of the year). He also set about building a nest egg for the owners. “We’ve picked up a couple of duplexes, and a condo in Florida,” says McClellan, who keeps an eye out for other investments, “So if we’re sitting on some extra money, it’s not sitting in a checking account.”

From Smaby’s perspective, adding McClellan to the mix was “a tremendous relief. And there was a sense of freedom, in that I was freed up to do what I did well and feel passionately about. And I think all of us ended up in positions like that.” Jordan led the field team and set the standard of craftsmanship. McClellan watched the store and herded paper. And as president, Smaby did what he has done ever since: sell the jobs, set the direction, and shape the company identity.

Design has always been central to that identity. Founded by architects, Choice Wood began by building only its own designs. The model would come to be called design/build, though, Smaby says, “At the time I don’t think anyone had ever heard that expression.” When Mulfinger and Susanka left, the company was without an in-house designer, but not for long. On sales calls, Smaby says, “I was frequently asked if we could design the project. And I got tired of saying no.” The company got back into the architecture business in the late 1980s, but the design division really took off with the addition of another partner, architect Todd Remington (who left the company in 2002 to practice and teach architecture in Colorado). “We went from one architect to about five under his leadership,” Smaby says. That by itself would not distinguish Choice Wood from any number of design/build firms that sprouted during the same period. What makes the difference is the fact that Choice Wood’s approach to architecture is so—for lack of a better term—architectural.

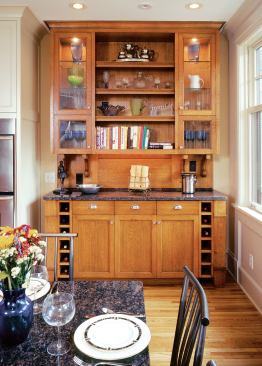

A tour of one of the company’s recent new homes makes the point. An infill project in an established Minneapolis neighborhood, the house combines traditional exterior forms with Modernist details. Its handsome, unpretentious stucco exterior and reasonable scale blend well with the older neighboring houses—an achievement in itself these days—but it is inside that Choice Wood’s work really shines. The first floor combines a contemporary open plan with finishes that are highly crafted and heavy on natural materials. A great room spans the width of the building, from a compact and beautifully detailed kitchen to a massive bluestone hearth and fireplace. The centerpiece is a staircase enclosed in an elegant cage of 3×3 fir spindles. It is rare enough to see this quality of work in the most ambitious of custom homes, let alone one of this modest size. “There aren’t too many houses like this out there,” Smaby says, “although this is exactly the kind of project we like to do. Exactly.” The ingredients include a realistic assessment of client need, a reverence for natural materials, a love of craftsmanship, and plenty of natural light. “And there’s also a kind of efficiency,” Smaby adds. “There are no silly ideas here; there’s not a lot of excess.” Every Choice Wood design represents a search for that sweet spot. “We call it the process of ‘finding the project.’ When that is done well, there is no excess, and it all fits together. That’s what sort of motivates me in my work.”