John Noltner Photography

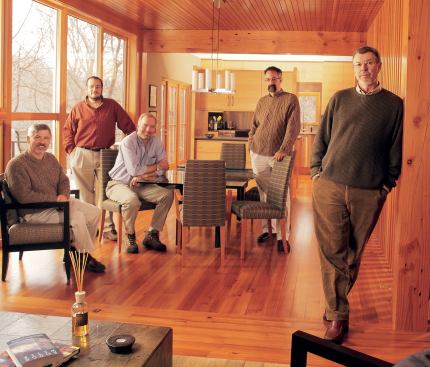

Choice Wood's brain trust — partners (from left) Mark McClellan…

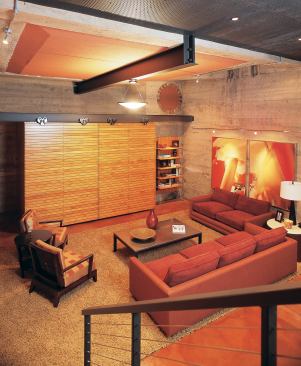

But while the company naturally favors building jewel boxes like this one, Smaby feeds a varied mix into the hopper. He likes to have at least one big new home in the works at all times to serve as a financial flywheel and to soak up labor hours when there is slack in the production schedule. Jobs like that are worth a bit of extra effort to bring in. For a $3 million project, he says, “We might knock it down to $2.8, then figure out how we’re still going to make money on it.” The company’s half-and-half balance of remodeling and new construction, also deliberate, provides a buffer against shifts in the market. “We’re pretty light on our feet that way,” Smaby says. “Most of our people are comfortable doing both. It’s part of our Cover Your Ass Program.” The company’s portfolio ranges from a $30,000 screened porch to new homes that average between $1 million and $2 million to an $8 million estate. As salesman, Smaby is motivated by “interesting design possibilities, really good people, or a chance to do something that helps someone out who needs it.”

“Nick is really the big-picture person,” says Jim Scott, one of Choice Wood’s two senior designers, “and part of his desire is to have the architecture division be as good as any independent architecture office around.” By the second or third client meeting, the design component is handed off to the architects, who conduct the project much as an independent firm would. “We keep enough of a separation in that respect to let the client realize that this is not a glommed-together event,” Scott says. Clients sign a separate design contract that typically specifies an hourly rate, monthly billing, and a cap at 10 percent of project cost. That fee is at the low end for architectural services, and as Scott explains, the connection between design and construction makes the deal an even bigger bargain. Early cost feedback from the construction side allows the architects to tailor a project precisely to its budget, avoiding the costly and disappointing cycle of over-designing and cutting back. “We’re always designing with budget in mind.”

For their part, the builders are always working with an architect on board. While Scott is explaining the benefits of this integrated approach, Jordan shows up, as if on cue, at the conference room door. He’s looking for a little hurry-up on lighting selections for a fast-track remodel. The lead time on the recessed cans is four weeks, and Scott has not yet finalized the lighting schedule. “What he’s asking me,” Scott says, “is can we pull the trigger on those cans today?” A couple of steps down the hall for an impromptu meeting with the electrician, and the matter is settled. Without in-house architects, Scott says, “It would have been two phone calls or three e-mails.” For Jordan, the advantage of in-house design is a no-brainer: “Ease of communication. We can turn on a dime,” and not just in the design phases. “Structural issues can be resolved quickly. A framer can call and say, ‘I’ve got an existing header that’s inadequate.’”

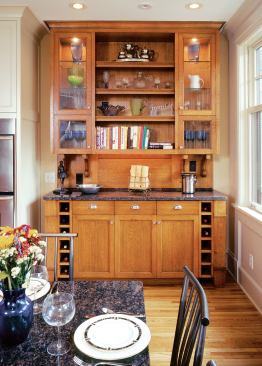

An interest in streamlining of that kind led to the addition of Choice Wood’s cabinet division and—a pattern emerges—a fourth partner. In the company’s early years, Smaby says, getting good custom cabinetry and millwork “was always a problem on our jobs.” One of the bright spots in the picture was an independent cabinetmaker named Andy Berg. “I liked his commitment and his willingness to try anything,” Smaby says. “He really liked challenges, and we gave him challenges. He always stuck with them until he found the answer, sometimes at his own expense.” The challenge of running his own business, though, was another matter. “He was working 60, 80 hours a week and not making any money. He was the salesperson and the engineer and the accountant, and he was in over his head.” Having recently come in out of the rain himself, Smaby says, “It occurred to me that we had the infrastructure that he needed. The pressure to sell would be diminished, because we would be selling for him.” Bringing Berg’s operation under the Choice Wood umbrella, Smaby and his partners figured, would keep their favorite cabinetmaker in business while allowing the company to “take some control over the quality and the price and the timing.” In practice, the arrangement has accomplished that and much more.

Despite the smile half hiding behind his beard, Berg, 47, is a pretty reserved fellow. On the subject of his work, however, he speaks with straightforward assurance. His cabinet shop, down a back hall from the company’s handsomely designed offices, covers 10,000 square feet and holds every tool short of CNC equipment. His team of two cabinet engineers and six full-time cabinet-makers, he says, is “capable at any time of doing anything.” Choice Wood’s biggest projects back up that claim, with cabinet budgets that would cover the cost of the median American home. But more than the flat-out production capabilities of his shop, Berg is proud of the synergies that have resulted from bringing his operation into the Choice Wood fold. “We’re problem-solvers for people in the field,” he says. “We do that for the architects too. We’re able to bounce ideas off each other and network.” Because his work is fully integrated with both the design and construction divisions, “I’m not just a cabinet shop,” he says. “I’m a contractor.” And, as a partner, Berg makes a strong case for putting his discipline at the heart of the company’s process. “We deal with every vendor: plumbing, electrical, lighting, flooring. A.V. equipment is a big issue, security systems … And we’re at the finish level, so it’s all got to be brought together at that point.” Having Berg’s work in-house improves not just the company’s process, but its product as well.

Among the partners, only John Greely represents something like homegrown talent. Now 49, Greely joined the company in 1990, having managed an architecture and graphic design firm. Since then he has made something of a grand tour of the company.

After a year of seasoning in the field, he moved indoors to become Smaby’s assistant. At various times he has been a project manager, construction estimator, millwork estimator, and production manager. Last year, when the company’s chief estimator retired early due to illness, he took over that job. Clearly a quick study, Greely has given a lot of thought to what makes Choice Wood tick. “One of the best things we have going for us,” he says, “is we have over 30 carpenters on staff. That’s huge.” Managing a team that size is a huge responsibility, and in recent years it has fallen mostly to Greely to keep everyone happy. “I do all the hiring and firing of the carpenters, the raises.” He also handles annual employee-performance reviews, OSHA compliance, and oversight of the home office. The company has long relied on Greely’s gifts of personal suasion to defuse potential conflicts with clients and subcontractors. “I call myself ‘glorified customer service.’ If someone has a problem, I’m the one who figures out how to fix it.” Like each of his partners, Greely broadens the scope of talent at the top. And as Smaby points out, Berg and Greely broaden the company’s time horizon as well. “Chris and Mark and I are sort of the old timers. It occurred to us 10 or 12 years ago to bring in some younger, enthusiastic partners. We want this business to continue, and at some point in the not-too-distant future some of the older guys are going to want to do something else.”

It is a commonplace in the custom home industry that the owner wears many hats. Successful builders find in time that to sustain growth—and their own sanity—they must delegate aspects of the job to subordinates. Steady growth and consistent profitability have brought Choice Wood a payroll of some 70 employees and an annual volume of $15 million. But following Smaby’s lead, the company has taken its own approach to leadership: putting new owners under the important hats. To Smaby, the benefits are clear. “In our current model I know something about our receivables and something about our payables, but I don’t lose any sleep over it.” Nor does he sweat the cabinet shop’s production schedule or worker’s comp; he has partners who will. “And there is comfort in that.” McClellan agrees. “Being a smaller part of a bigger pie has some attraction. There is a sense of security in having some people in there doing things that you can’t do.” Having that kind of backup also allows the owners some flexibility in the roles they choose for themselves. Several years ago, McClellan decided to pursue a longstanding interest in real estate sales. “That involved him getting training, essentially removing himself from his role as project manager,” Smaby says. “And we all supported that, even though there was no real return for several years.”

Until last year, Jordan, 54, worked in the field, acting as foreman on the company’s most important projects. And while he now heads production (having taken over for Greely when he became chief estimator), Jordan remains a builder’s builder, a true believer in the nobility of his calling. “It’s creative,” he says. “It’s real. There’s proof that you were there, every day.” After decades in the field, he still considers a well-framed roof “a true work of art” and those with the skill to produce one “an exclusive club.” One of Jordan’s favorites among the company’s programs is Choice Wood University, an informal seminar series on construction technique. “We take one night a month and pick a topic,” he says. “Last night it was hip roofs.” Ten carpenters attended, if you don’t count the one who happens also to be an owner. “They were on their own time, talking about what they do and how we do it. Some of them were rookies, and some of them were journeyman carpenters. Sitting around eating pizzas. I loved it, I just loved it.” Jordan sees his place in a lineage of craftsmen, and relishes the role of mentor that he has earned. “You take a young carpenter and tell him, ‘You’re going to know how to do something not that many people know how to do anymore,’and they just light up.” It is unusual for an owner of a $15 million company to wear a tool belt, but Smaby defends Jordan’s long tenure in the field. “Some of us are a little bit removed from the heart and soul of what we do,” he says. “Chris is not. He knows what it is to be a builder, how long it takes to build things. To have that voice in our boardroom, if you will, has been very valuable. It kind of brings us back to what we are doing.”

Each of the company’s five owners plays an equivalent role, bringing capabilities that complement those of his partners. And if balancing so many leaders at the top of a not-so-big company sounds like a difficult trick, it has never seemed so to this group. “I think there’s kind of a natural hierarchy, if you will, a natural respect given to the more senior partners,” Smaby says, but decisions at the weekly partners’meetings are reached democratically. “It’s rare, but there have been occasions when I’ve felt passionately about an issue, my partners haven’t supported me, and we haven’t done it,” Smaby says. “And I’ve accepted that.” The bucket of cold water is administered, often as not, by McClellan (“The finance guy is always the negatron,” he says). But such natural tensions are grounded in a system of mutual acceptance and support that reflects the maturity and hard-earned wisdom of the partners. “I think that each of us has had a bad year or two, mostly for personal reasons,” Smaby says. “I think one of the things that makes us strong is that we let each other have a bad year.” At Choice Wood, that generosity is founded on a genuine optimism about the power of shared endeavor. “I’ve never had the sense that I was giving something up to bring in a new partner,” Smaby says. Rather than worry about getting a smaller piece of the pie, “What we try to think about is, let’s make more profit. A new partner is value added. The pie is going to be bigger.” That philosophy does not rule out further expansion in Choice Wood’s executive suite—perhaps with a partner in charge of design, Smaby says—and could well see the company through to a third generation of leadership. Stay tuned. This show could be in for a long run.

Multiple Listings Adding a real estate brokerage to a building and remodeling business makes so much sense, you might think that Choice Wood’s partners planned it that way. In truth, company CFO Mark McClellan just really, really wanted to buy and sell houses. “It was all driven by my interest and desire,” McClellan says. He had dabbled in the field for some time—“I had my first license back in the ’70s,” he says—but had never gone much beyond advising friends. Still, the pull was strong. “I would find myself stopping by at open houses on Sunday anyway,” he says. About five years ago, with Choice Wood on such solid financial footing that he could afford to feel restless, “I decided maybe we should make this part of the business.” Honoring McClellan’s inner broker required some adjustments from his partners (while he remained in charge of the company’s finances, he shifted production management duties to others) but resulted not only in a happier CFO, but a better, more well-rounded company. Drawing, in part, on a deep and loyal base of construction clients—and without spending a penny on marketing—Choice Properties now lists from three to seven houses at any one time, represents an equal number of buyers, closes some 20 deals in an average year, and delivers a profit stream to the parent company.

“It’s definitely a service that works well with the rest of what we do,” says company president Nick Smaby. On remodeling sales calls, he says, “I’m constantly asked if it makes more sense to remodel or to sell.” That can be a hard question for an honest builder to answer. Now, when the situation warrants, “I’m able to say it makes sense to look around, and, by the way, we have someone who can help you.” Unlike traditional builders and real estate brokers, McClellan adds, “We can do it all and have no agenda to push you one way or another. We can collect all the data, we can help you process it, but the final decision is yours. The other benefit is, my association with the building side of it allows me to have a sense of what the possibilities might be on a property and, more importantly, what the costs are.” Smaby has tested the model by listing his own house with his partner. One interested buyer said that the house’s single garage was a deal-breaker, but the Choice team whipped up a concept plan for a second garage, researched the code issues involved, and kept the deal alive. “I’m not sure there’s another real estate company that could pull that off in a day and a half,” Smaby says. “We bring that kind of collaboration to a whole lot of situations.”