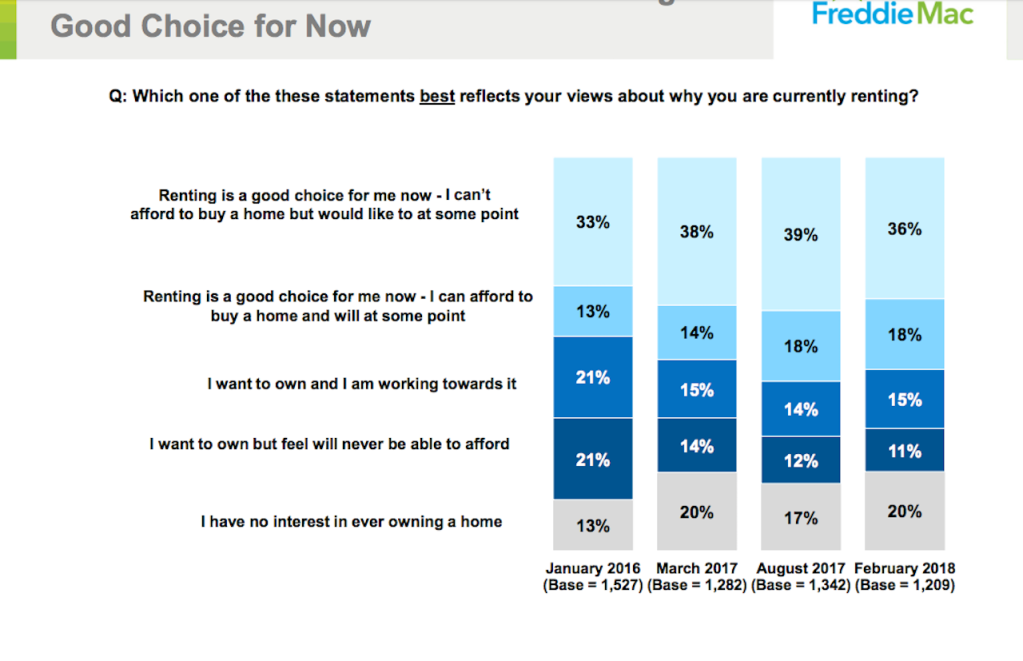

A Freddie Mac survey released earlier this month caused a stir. More people, its studies say, prefer to rent than to own their home. Here is the top line finding:

Growing segments of the population—baby boomers and Generation Xers in particular—are showing less interest in owning a home. The latest “Profile of Today’s Renter” reveals that despite growing economic confidence among renters, affordability remains dominant in driving renter behavior.

Specifically, the spring Profile finds a total of 67 percent of renters view renting as more affordable than owning a home, including 73 percent of baby boomers (aged 53-71). Similarly, 67 percent of renters who will continue renting say they will do so for financial reasons—up from 59 percent just two years ago.

Home builders we talk to tell us there’s no shortage of people, on the other hand, who clamor to get out of renting and get into homeownership. The market for homeownership demand, many say, has not only not been hurt by tax law changes that went into effect in late 2017, but has been bouyed by it. Here’s how Lennar executive chairman Stuart Miller phrased it in commentary about Lennar’s latest earnings release:

“The recently passed Federal Tax Act continues to add additional momentum to the economic landscape. While many have been concerned about the effects of the new tax law on housing, it is proving to be a net positive to the wallet of our customer base and stimulative to the economy overall and that is good for housing…Additionally, the doubling of the standard deduction helps apartment dwellers accumulate the savings they need for a down payment to purchase a home and therefore stabilize their housing costs.”

How can both narratives be true?

Two explanations come to mind.

One is that solid job growth for several years has fueled a release of pent-up household formation growth. More households period mean that surveys and behavior on housing preference could support favorable changes in preference for both renting and owning.

Another possible way to account for why seemingly conflicting trends can co-exist crops up when you look at age demographics and consider the lifestages that correspond with typical household patterns.

Pew Research tells us this week, “Millennials are the largest generation in the U.S. labor force.” Pew analyst Richard Fry punches in with this take on U.S. Census-based numbers:

More than one-in-three American labor force participants (35%) are Millennials, making them the largest generation in the U.S. labor force, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data.

As of 2017 – the most recent year for which data are available – 56 million Millennials (those ages 21 to 36 in 2017) were working or looking for work. That was more than the 53 million Generation Xers, who accounted for a third of the labor force. And it was well ahead of the 41 million Baby Boomers, who represented a quarter of the total. Millennials surpassed Gen Xers in 2016.

Let’s then put this together with some observations about wage growth, which has been hibernating for a decade, but which is showing recent signs of life. Atlanta Fed senior policy advisor John Robertson and economic policy analyst Ellyn Terry do wage growth analysis that’s particularly illuminating when you look younger workers–Millennials–and what’s happening in their incomes.

Our analysis suggests that median wage growth of the population of wage and salary earners is currently higher than the WGT would indicate, reflecting the strong wage gains young workers experience in a tight labor market. Moreover, the increasing share of older workers is acting to restrain median wage growth.

We can infer here that wage growth among younger workers has been more dynamic–but given that younger worker total income is still a smaller percentage of household incomes in aggregate, overall wage growth is slow.

We can also infer from the demographics that family formation–coupling–is going on as part of the millennials’ rites of passage into real world behaviors that reflect their values. As singles, many of those Millennials might have said that renting an apartment looked like all there was from an affordability, from a preference for connection, and from a proximity to work standpoint.

Moving on from being single to becoming a couple, and then from there to potentially expanding into a family can occur over a compressed period of time, especially since many Millennials have already reached their early to mid-30s, and are only recently out of doubled-up or parents’ households. As the Zelman & Associates team notes here in the latest The Z Report, households that couple are as often as not two income households, and dual-income households–especially ones intent on making or expanding a family–can be the ones who six months ago might have thought they’d prefer to rent because they couldn’t afford homeownership, and now are both capable and motivated to buy. Zelman’s note observes:

“Assessing affordability pressures based on wage growth alone would likely understate household finances that are benefiting from a higher frequency of dual incomes.”

So, it’s entirely conceivable that data could support both increases in preference for renting and a motivated move toward homeownership, clearly evident in the pace of orders and absorptions home builders are telling us about these days.

If you haven’t yet caught it, Metrostudy chief economist Mark Boud’s latest Outlook looks at real-world, on-the-ground homeownership supply and demand math like no other source out there, and models what is likely, not only around the next corner, but around the one after that. Check it out here.

Of course, nothing beats Mark live and in person, and he and Zillow chief economist Svenja Gudell will engage in a data-duel, looking at the dynamics of existing, for-sale, single-family for rent, and every other housing trend to speak of as part of our Housing Leadership Summit program coming up in a few weeks. If you haven’t yet registered, there are a few seats remaining, so click here to sign up today for that opportunity to glimpse ahead with Mark and Svenja.