For years, it seems, home builders and the ecosystem of investors, developers, partners, and manufacturers that support them have been competing with vague, dark, unfamiliar rivals. Distressed resales, multifamily rentals, virtually no mortgage lending, a real estate landscape thickly blanketed with permafrost, to name a few such enemies.

Now, though, tables are turning. Foreclosure and distressed sales are normalizing, rents are too high, mortgage lending is loosening up, and demand, it seems, is acting like an awakening giant after a long hibernation. But home builders are finding they’re having to compete harder than ever–for good lots, for fresh, bright, capable talent, for reliable access to subcontractor skilled labor, for steady flows of project-level finance and pipeline development fund. And they’re competing not with fuzzy, mysterious forces, but hand-to-hand, and head-to-head in the trenches, with none other than each other.

Gone are the days builders might create a quilt-work of projects that, to at least some degree, staked out a customer segmentation position or a product type or a land position that aimed to differentiate their value proposition from one another in a market. Now, by and large, fewer, more powerful, more motivated competitors now aim to eat your lunch, partly because supply is so constrained and partly because the flow of demand is still far from robust at just-under 600,000 new home single-family sales a year. It’s brute force against brute force, especially as the strategic impetus shifts toward higher-volume, faster-paced, lower-margin entry-level first-time buyers in each given geographical arena.

That said, shrewd, precise, and decisive take-no-prisoners land strategy, operational systems flow, and sales initiatives are the skill-set flavor of the day in home builder land. When things accelerate all is well except if something is wrong in the works. Then, things go wrong very fast and very expensively.

That said, one of the big challenges for many home building organizations as they wrap up their budget and business visibility processes leading into 2017 is how and where to invest for well beyond 2017 with so many questions around the economy, jobs, incomes, and attainable housing stock.

Here are a few analyses that should at least provoke helpful and directionally sound questions, as it’s good companies that engage with and fix what they can’t yet see.

First, is this broad-brush take from Zillow chief economist Svenja Gudell on the ever-wider gap in housing values that separates the median top-third of homes vs. the median bottom-third. Especially as expectations rise around the onset of a surge in first-time young-adult entry-level type buyers, it’s helpful to understand the compositional make-up of that universe we might normally define as the first-time buyer universe. Gudell notes that the gulf in home values matches up to a just-as-noteworthy polarization in household incomes. She writes:

In 1996, the median top-third home was worth 2.75 times more than the median bottom-third home. Today, typical top-third U.S. homes are worth more than 3.2 times as much as typical bottom-third homes. These changes in home values by tier mirrors changes in incomes over roughly the same period. In June 1999 the median top tier worker had an income of $88,000, 5.8 times greater than the median bottom tier worker ($15,200). 16 years later, the top tier worker made more than 6.6 times the bottom tier worker at $128,640 and $19,338 respectively.

Gudell’s work here exposes a filter through which home builders–who try to price new homes in an elastic, premium-to-existing-home value context–can look at relative affordability, attainability, and positioning of their product. We’re seeing a lot of builders position at least their first initiatives in lower-price tier communities as “entry-level plus” type product that might appeal to a mid-30s, early stage couple heading for family expansion.

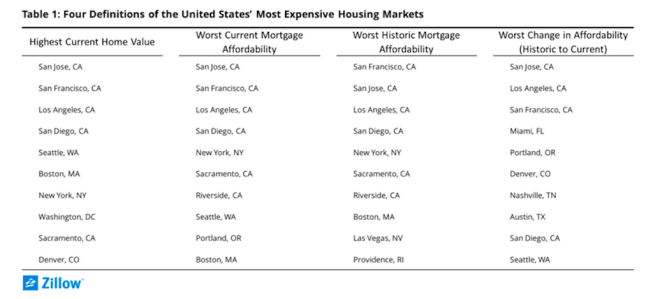

The second is another Zillow analysis, this one from senior economist Alan Terrazas, who looks at the strong correlation between housing’s most expensive markets and those same markets’ strong track record as job creation magnets. Terrazas’ big take-away:

There is a clear upward trend in the share of total U.S., nonfarm employment located in each group of markets over the past two decades (figure 1). The share of total U.S. jobs increased in these expensive housing markets in the run-up to the early-2000s dot.com bubble and bust, then experienced a drop in their share of national employment for much of the 2000s. This turned around with the end of the recession, and expensive housing markets are again seeing a historically high share of national employment. Currently, roughly one in five U.S. jobs is located in one of the 10 metros with the highest overall home values, worst current mortgage affordability and/or worst historic mortgage affordability.

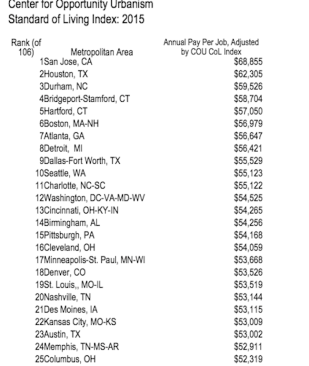

But, what happens when you flip that premise on its head, and look, as New Geography demographers Joel Kotkin and Wendell Cox have, at paycheck power rather than strong job growth in highly unaffordable markets? As Kotkin writes here:

Center for Opportunity Urbanism senior fellow Wendell Cox has developed a set of rankings that identify metropolitan areas where salaries are relatively high relative to costs, and you get more for your paycheck. Our list is geographically and demographically diverse, both in terms of the top 20 and the places closest to the bottom.

There are two strategic tacks builders can take in a winner-take-all housing recovery leg that pits builder against builder in competition for talent, trades, lots, capital, and customer. One is to dominate the market from a percentage of share standpoint, as D.R. Horton has done in resurgent Atlanta. The other is to build where the others aren’t, which is what Horton and Clayton Homes seem to be up to as they play out their geographical manifest destinies.

Note that Horton is playing both strategies and playing them extremely well. It may be said, too, that few would describe D.R. Horton as anything other than an incredibly smart, aggressive, and able competitor. The people there engage with and fix what they can’t see even as they focus and execute on what’s right before their eyes.