James West

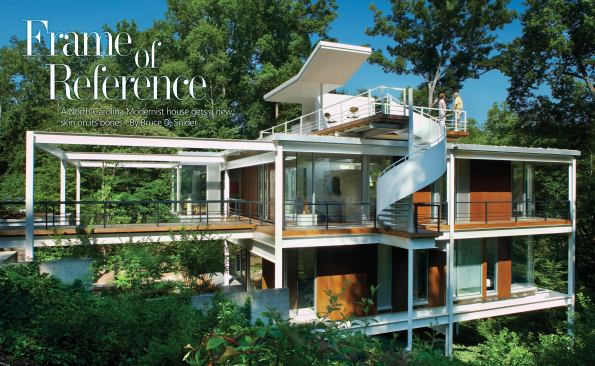

An existing steel structure serves as the armature for an enclos…

Time marches on. But in custom building, it doesn’t always march in a straight line. Take this house. Only 40 years old and fast headed for an early grave, it was rescued by a team of builder/architects who had not yet been born when it was new. These young craftspeople, some of them fresh out of architecture school, rebuilt it in a style that is older than their grandparents. Which, of course, we call Modernism. In spite of the looping path, however, the building arrives at the present day in very fine form. The bones of its once deteriorating structure support a house that is visually stimulating, great fun to live in, and—this time—built to last.

Vinnie Petrarca, 34, and his crew at Tonic Design had been watching the house for a while, hoping to get their hands on it before it got scraped off. Modernists by training and inclination, they liked its flat-roofed form, its exposed steel structure, and the way it seemed to float in the treetops of its steep, wooded site. The odds of finding a patron who shared their enthusiasm, though, did not look good. The house sat on a desirable lot that could be subdivided to carry two new houses. Worse, the building itself was in a miserable state. The steel frame and concrete floor decks were intact, but the rest was rapidly heading south. “It was a melting wood structure, just falling apart,” Petrarca says. When he showed the place to an Ohio couple planning to retire here in Raleigh, N.C., curb appeal was in notably short supply. “It was a rainy day in January,” Petrarca remembers, “and there were tarps all over the house.” Still, he pleaded its case. Despite appearances, he maintained, the house was still “strong in concept.” The couple left unconvinced.

Soon after, though, on a trip to Los Angeles, they followed Petrarca’s advice and visited architect Pierre Koenig’s Case Study House #22, a glass-walled icon of mid-20th-century Modernism. The house, which cantilevers over the brow of a steep hill overlooking the entire Los Angeles basin, is early-1960s zeitgeist in a bottle: light, transparent, and cool. This, Petrarca had told them, was what he had in mind for the Raleigh house. And that, apparently, was that. The clients returned, settled on the property, and gave Tonic a remarkably free hand in plotting its second incarnation. “The only program statement we had was, [the owner] said he wanted the most loft-like house or the most house-like loft,” Petrarca says.

Modernists like nothing better than a structural grid, and Tonic wasted no time in picking the building down to its bare bones. “We stripped everything out,” Petrarca says, leaving only the steel frame and concrete decks. Built down-slope from its driveway and parking area, the original house snugged up close to an L-shaped concrete block retaining wall. Petrarca sacrificed some square footage to pull the house away from the retaining wall, creating a walled garden at the building’s lower level. The original steel roof girders remain, delineating an open two-story volume spanned by an entry bridge from the parking area. “It’s kind of an upside-down house,” says Petrarca, who located the entry and living spaces on top for better access to views and daylight and maximized both by enclosing much of this level in floor-to-ceiling glass. At these areas, the walls pull back within the steel frame, creating a narrow balcony that wraps the perimeter. The latter provides ready access to the outdoors and, prosaically but no less importantly, facilitates cleaning all that glass.

The glass-wall paradigm spurred other heads-up decisions. Small, floor-mounted fixtures wash light up the surface of the glass and keep it transparent at night. Using aluminum-frame storefront panels held the cost down, but Petrarca found the available operable windows too clunky. Instead, he specified narrow, floor-to-ceiling doors screened with perforated steel. While the holes in the latter looked small enough to keep the bugs out, Petrarca says, “We put a couple of mosquitoes in the jar and put the perf metal on top to make sure.” Two bays project beyond the basic cube of the building: a glass-walled sitting area off the kitchen that the owners call “the sun porch” and a two-story mass sided in shiplap cypress. Solid perimeter walls that stand within the steel framework are sided with full-height panels of Cor-Ten steel. In the best Modernist form, intersecting walls meet at frameless glass-to-glass connections. “You always dissolve the corners,” Petrarca says.