James West

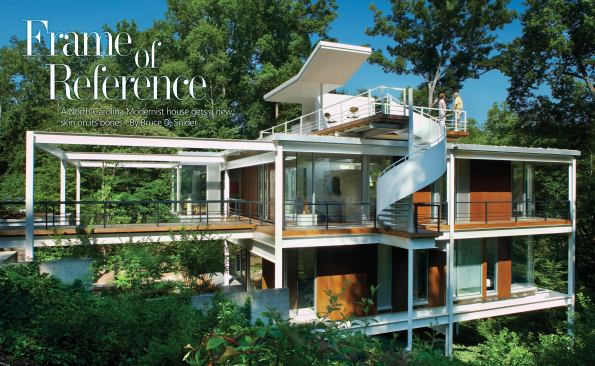

An existing steel structure serves as the armature for an enclos…

This highly evolved shell contains an equally sophisticated interior. The entry level clusters smaller, more contained spaces around the elevator shaft at the center of the plan, allowing the major living spaces to run to the outside walls. Abbreviated partitions distinguish function areas without isolating them. Rectangles of white wall surface backdrop the owners’ collection of mid-20th-century art and furniture. The effect, Petrarca says, is “somewhat period. All the furniture is low; none of the furniture touches the floor.” The main stair, a welded steel unit with Brazilian cherry treads that hangs by a single steel stringer buried in the wall, extends the theme of levitation. An 8-foot-long skylight over the stair pours daylight through the oversize stair opening to the lower level’s large circulation core. More private and enclosed than the living spaces above, the lower-level rooms enjoy more focused views. The twin guest bedrooms overlook the wooded slope down to a wide creek. A glass corner makes the laundry room something of a woodland retreat. (The den, painted Buckeye red, offers seasonal views of Ohio State football.)

The master bedroom’s outdoor focus is the garden defined by the original retaining wall, which the builders adorned with a fountain they fashioned from panels of oxidized steel. As Petrarca explains: “We had all these extra pieces of Cor-Ten . . .” It’s the kind of improvised solution that seems naturally to follow when architects take the role of general contractor. Daily presence on the jobsite and personal relationships with subcontractors give design/build architects a different perspective on the project, Petrarca says. “When we’re doing brake metal, whether the guy has an 8-foot brake or a 10-foot brake influences the design.” The phenomenon came strongly into play in the building’s rooftop deck, with its wing-like canopy (see “Controlling Overhead,” page 75), but Petrarca can point out another dozen such features that evolved during the construction phase.

The existing frame facilitated on-site design, serving as an armature for mocking up walls. The foot-high band of horizontal glass at the breakfast area, tailored to the owners’ seated heights, is the product of such fine tuning. The steel skeleton did have its downside, Petrarca hastens to add. “It was a blessing and a curse. You don’t use a nail and a hammer; you drill for a couple of hours and bolt it together.” But a couple of hours amount to little when measured against the proper lifespan of a house. Recognizing real value and working to preserve it, Petrarca and his company salvaged a fine and durable legacy for a building that could easily have been lost to the passage of time.

Project Credits:

Builder: Tonic Construction, Raleigh, N.C.

Architect: Tonic Design, Raleigh

Living space: 4,600 square fee

Site: .87 acre

Construction cost: $260 a square foot

Photographer: James West

Resources: Bathroom plumbing fixtures: Grohe and Kohler; Cabinets: Woodpecker Enterprises; Dishwasher: Bosch; Fireplace: Heat N Glo; Garage doors: Clopay and Lift-Master; Garbage disposer: In-Sink-Erator; Hardware: Omnia; HVAC equipment: Trane; Kitchen plumbing fixtures: Elkay and Grohe; Lighting fixtures: Halo, Lightolier and WAC; Oven: Bosch; Paints: ICI Delux, Samuel Cabot, and Sherwin-Williams.

Details: Controlling Overhead

The roof deck that tops this house gives it a playful, treehouse-like aspect, but the structure that holds it up is all business. “We always knew we wanted to put something on the top of the building,” says designer/builder Vinnie Petrarca, “to give it more vertical presence and to get up here to see the horizon.” To support the new deck, he designed a steel frame that floats above the rock-ballasted roof on four columns that rise the full height of the building, “basically like a table.” The wing-like canopy is supported at one end by steel beams that cantilever out from the elevator house, at the other by a slender steel post. In between, Petrarca says, “There’s a lot of steel, to get it not to torque in high winds.

“We asked the best steel erector, and they said, ‘We can’t do this for less than $100,000,’” says Petrarca, who decided that, with a little help, his team could. “We ended doing all the shop drawings, ordering all the steel from the steel mill, and marking it up.” He hired a small steel erecting company to cut and fasten the members and an all-terrain crane to lift them into place. “There was a lead guy, and he had four helpers, and one of us went with each of them.” From there, he says, it was just like carpentry. But instead of a saw, the power tool was “this guy with a torch. It was a lot of fun.”

The Builder: Club House “Everybody who works for us has an architecture background,” says designer/builder Vinnie Petrarca. But don’t take that to mean that Petrarca, 34, and his crew are satisfied to sit inside and draw plans. Their office is a warehouse-like space in an industrial park. At any time, staff members are as likely to be out building something as in here drawing plans. Designers cycle from the office to the field when their projects go into construction, and the whole team engages in occasional SWAT operations to make something better or less expensively than a subcontractor would. For a group of young people animated by the love of building, this looks more like a lifestyle than a profession. But Petrarca’s model of “construction-led design,” works as a business model too. Even here, in the educated precincts of North Carolina’s Research Triangle, Tonic’s Modernist style serves a niche market. Generating builder profit as well as design fees allows the firm to focus on a small number of projects, do their best work, and make a living at the same time. “If I was just doing architecture, it wouldn’t work,” Petrarca says.

The benefits go beyond happy architects. “The myth is that Modern houses don’t sell,” but the comps he collects prove otherwise. “Because we’re the contractor,” Petrarca adds, “we can pull the construction loan really early, so [clients] can finance the design over 30 years.” And with builders in control from day one, the budget is transformed from a smudged windshield to a high-resolution imaging system. “As a design/build architect, you have access to all these subcontractors. When we look at these houses now, we see the welder, the mason. We can do a light set of drawings, but we know what these guys are going to cost.”