Editor’s note: The data in this story has been revised from its original version. Changes were made to Toll Brothers’ gross margin percentage, pre-tax income, and land-related charges. Numbers of sales per community per month to break even were revised for all companies.

The rules of evolution are hard, simple, and irrefutable. When environmental conditions change, long-term survival requires adaptation. Failure to adapt means eventual extinction. It may take a month, it may take years, but eventually species that don’t adapt disappear.

Those rules have held true for the home building industry. Sometime in the late summer of 2005, the number keepers of home building say, the climate for U.S. home builders began to change from that of a lush, overgrown rain forest to something that, nearly six years later, resembled the Sahara. In 2011 a few oasis markets remained here and there, but, for the most part, the industry continued to operate in a harsh, ruinous climate.

Many home builders spent the next several years operating their businesses as usual, praying for, and expecting the rains to return, but the weak among them began to die. Others shrank, some fell into stasis. Bankruptcy, either to reorganize or dissolve, became the fate of others. As is usually the case, the change was more damaging to the small and disadvantaged builders, primarily privately held companies that were overextended and who lost their capital sources. But it hit the publicly traded builders hard as well.

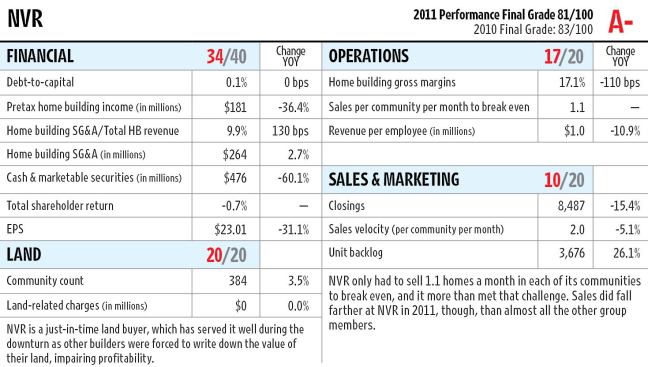

There were 21 builders on Big Builder’s first “Public Builder Report Card” in 2006, which tallied 2005 builder numbers. That year the group closed a total of 340,243 homes. This year there are 13 builders in our report card. Among them, they delivered 82,037 homes in 2011, fewer even than 2010. Of the builders left on the list, only four were profitable for the year and only one, NVR, was significantly in the black. The rest continued to bleed red ink, less red than in past years, but red nonetheless.

By 2011, the more successful builders had finally stopped waiting for things to get better and started working to adapt and live on the meager fare the market offered. For some that meant admitting that their core business practices weren’t working anymore and making big changes to the way they do business.

The more adroit and savvy learned to hunt better for land in the best places at the best price. They created new home designs and sales practices that made prospective buyers stop looking at shopworn foreclosures. And they started working to squeeze some profit out of the houses they managed to sell by continuing to shrink staff to match sales, whittling down construction costs, and rethinking which options to include in their homes.

EVOLUTIONARY PAINS

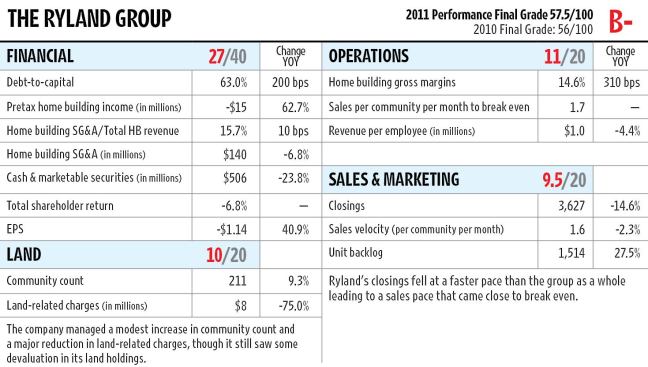

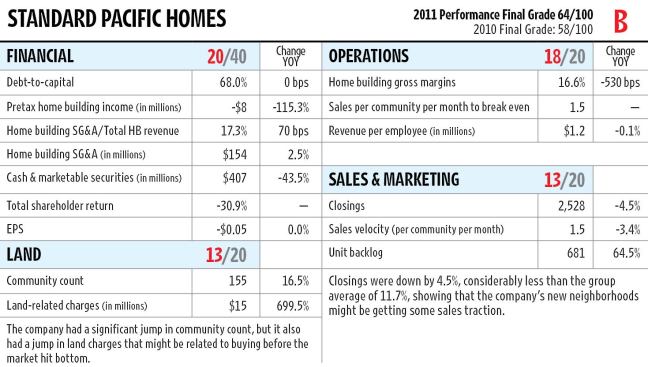

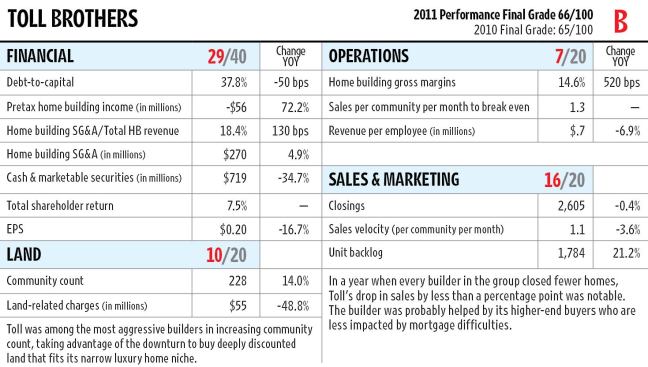

Inside the Report CardsThe Big Builder Public Report Card is an annual data presentation that combines original and researched information with proprietary analysis. This year’s presentation of key financial and operational data for the public builders includes information from investor presentations, company filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission, and analyst reports. In some cases where a few companies failed to disclose key metrics, Big Builder used estimates from Adam Rudiger at Wells Fargo. We also incorporated feedback from investor relations and senior financial officers. This year our 2011 public builder universe includes 13 home building companies traded on the U.S. stock exchange whose primary business is building homes. Avatar Holdings (now AV Homes) and Comstock Homebuilding were excluded because their 2011 sales volume was low, and it would have been unfair to include them among a group composed of much larger–volume builders. The same was true for Brookfield Homes, beginning in 2010. The evaluation breaks quantitative data into four categories: financial, land, sales and marketing, and operations. Because a public company’s overall performance is so closely tied to financials, we weight that category more heavily. This year’s results were compiled by Jamie M. Pirrello, a veteran of the home building industry who is now managing partner of Berkeley-Columbia Consulting Group. Pirrello worked with Hanley Wood editors to analyze and grade public builder performance. The Big Builder Report Card has evolved over the years but its original structure was created six years ago by former housing analyst Barbara Allen. |

|

1

of 13

After years of troubles and earnings that fell short of the publ… |

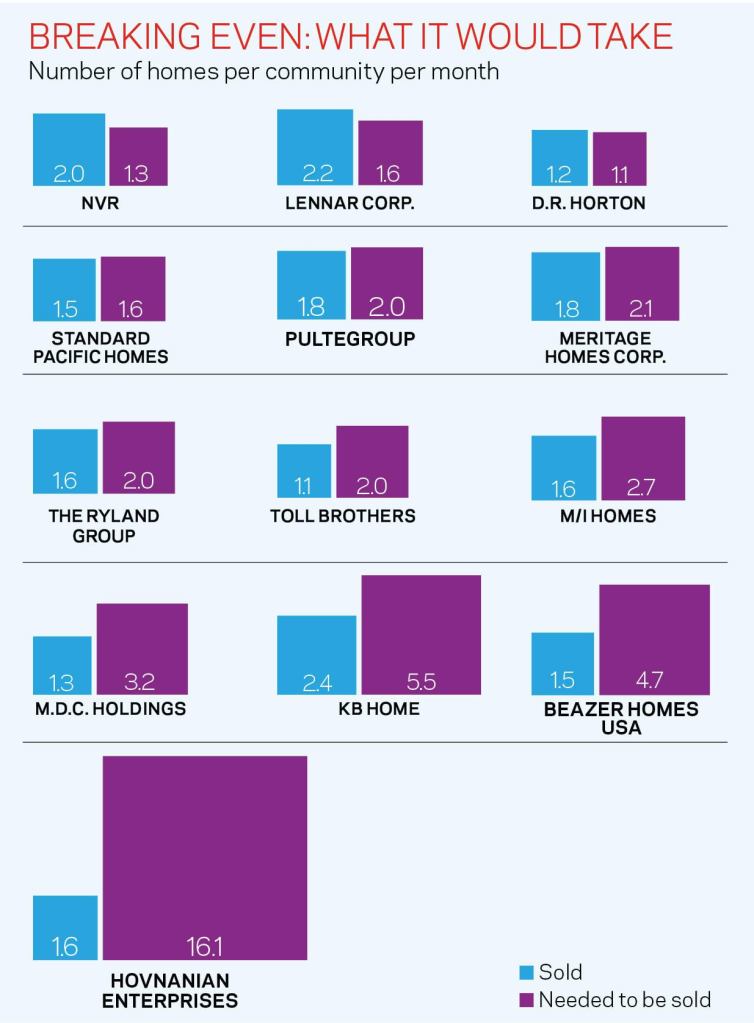

Some NotesCash: This year we are using the total of unrestricted cash and marketable securities for the cash number. In previous years we used only cash. The change was made after taking into account the statements by several home building executives that their cash equivalent numbers are made up of highly liquid investments that can be converted to cash quickly. Counting lots: We calculated builders’ supply of lots by dividing their total year-end lot count by their 2011 closings. The assumption is that 2012 will be a flat sales year. New numbers: Last year’s report added a velocity number, average monthly home sales per community, to our sales and marketing analysis. This year we built on that by adding a calculation for how many units a builder needed to sell to break even in our operations analysis. Here’s how we came up with the break-even number: SG&A divided by average gross margin per unit (home building gross margin divided by closings) equals total break-even units. Total break-even units divided by average communities (beginning-year communities plus ending-year communities divided by 2) equals total break-even units per community. Our total shareholder return calculation formula is ending-year stock price minus beginning-year stock price plus dividends divided by beginning-year stock price. |

While some builders worked hard to adapt, with mixed degrees of success, others stuck to business models that no longer worked, hoping things would go back to “normal” soon. They didn’t get serious about making real changes until 2011. Some made changes that were too little, too late, or that didn’t help. Even the best struggled while trying to adapt to a low-volume market. Some even slid backwards in 2011.

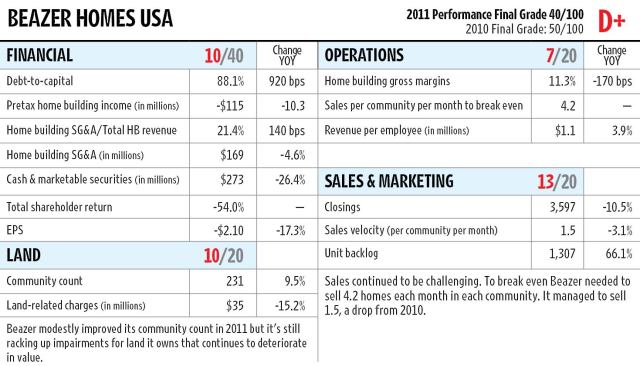

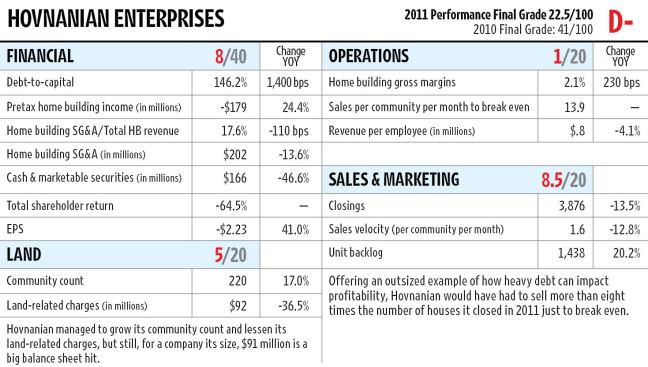

Builders such as Beazer Homes USA and Hovnanian Enterprises, which both started out the downturn in worse shape than the others, are having a tough time pulling themselves out of the holes they dug through heavy debt, poor land they paid too dearly for, or, in Beazer’s case, criminal investigations that kept the company under siege for years.

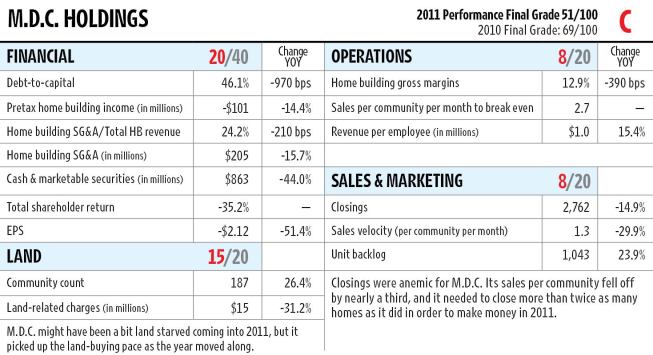

Then there were a few who started out the downturn riding high, such as KB Home and M.D.C. Holdings. Their results have deteriorated even more than others recently, as their better position at the onset of the downturn delayed their efforts to adapt.

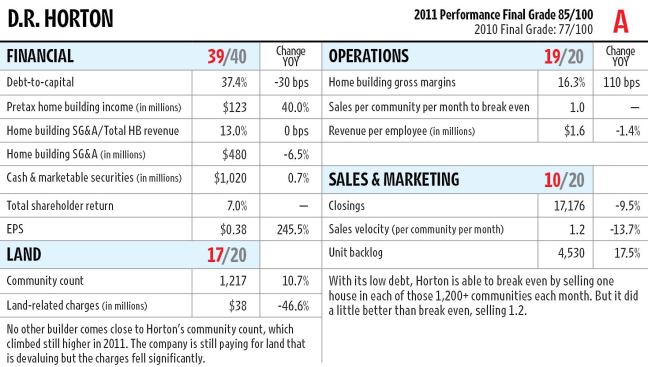

But struggling while attempting to overcome such a severe recession is no embarrassment. No builder has been left untouched. Even gold-standard builders such as NVR and Toll Brothers revealed chinks in their armor when each reported less-than-stellar results for some metrics in 2011.

“Last year’s challenges [for builders] were adjusting their businesses to try to generate profits in the existing environment, i.e., no increase in demand,” sums up Wells Fargo Securities home building senior analyst Adam Rudiger. “Some companies have done some heavy lifting in restructuring their businesses while others have yet to rightsize their ship.”

ADMITTING AND FIXING MISTAKES

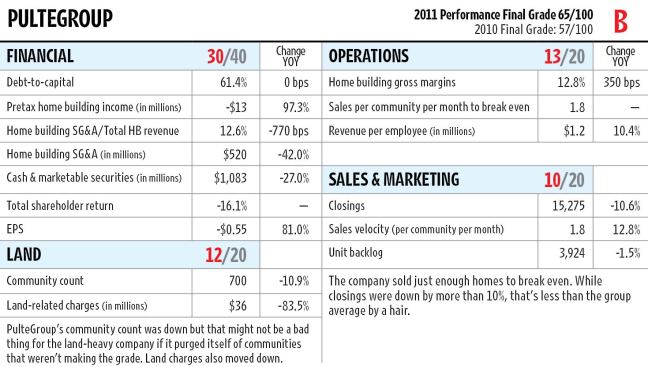

Conditions have taken some of even the biggest, oldest, and most respected building companies to school, teaching humbling lessons the hard way. Richard Dugas, CEO of PulteGroup, the largest builder by revenue in the country, readily admits his company was left holding too much land when the market tanked. It held onto that land through the recession even as other builders, who held land by option rather than title, more easily dumped their holdings. Then it bought Centex, bringing even more land onto its books.

“I will tell you in hindsight … we did overdo it on the land side,” says Dugas. “That doesn’t mean that we don’t value what we have, but one of the things we are learning is that you can control land without having to own it.”

The experience led Pulte to create a more strenuous method of evaluating land’s value to the company, says Dugas. PulteGroup once used a single hurdle rate for all land purchases, whether it was 3,000 lots or 30, or whether build-out was one year or 20. The company’s new land formula requires higher returns for longer-term projects that innately present more risk. PulteGroup is even considering selling some lots it isn’t planning to use in the next five to seven years to other builders or for other uses so it can invest the proceeds to pay down more company debt, which dropped by $300 million last year.

PulteGroup also made large cuts to personnel last year, helping plump its skinny margins, which were among the worst in the group in 2010. The result was improved margins and SG&A versus revenue numbers that were second only to NVR last year.

“It’s a sad fact, but we’ve kind of gotten good at downsizing as a company,” says Dugas. “It’s a little hard to get excited about it because it’s on the backs of others.”

More margin work is in the offing as the company eliminates standard features it has been including in every home, selling them as upgrades instead. Home prices couldn’t be raised high enough to cover the costs of features such as granite countertops in every home’s package and still deliver decent profit margins.

PulteGroup is also making other changes it hopes will increase sales and boost profits. It is exploring high-tech solutions to design centers such as handing shoppers iPads they can use to add and subtract various options costs as they move through model homes. And the company has curtailed speculative home construction because the homes without a customer order tend to sell at a notable discount compared to pre-ordered homes.

“There is nothing like a good downturn to examine what works and what doesn’t,” quips Dugas as he outlines the operations changes.

Next: FINDING THE OASES

Learn more about markets featured in this article: Denver, CO.