When a builder hands over the keys to a new house, chances are that the only path on the property is a walkway from the driveway to the front door. Or, in an urban setting, from the front door to the sidewalk. Paths are purposeful; they usher people from here to there. Like the driveway, they provide a hard surface for high-traffic areas, protecting the lawn and providing solid footing. But on a new property, paths are also the starting point for an imaginative landscape. They invite visitors to stroll and stop, change perspective, or see what’s around the bend. A well-designed network of paths organizes an entire outdoor area, so that it unfolds effortlessly from the house itself.

For Julie Moir Messervy, a Wellesley, Mass., landscape designer and the author of numerous garden books, including Outside the Not So Big House, which she co-authored with architect Sarah Susanka, the concept of house isn’t complete without the landscape. And a path, or series of paths, is what knits the two together. “If you think of a property as being home, then the path doesn’t stop at the front door,” she says. “The front walk becomes the foyer and then the hallway; it opens up to a pool of space in the living room and dining room, then moves out onto a deck or screened porch and into the landscape again.”

Messervy says that paths can reflect the owners’ personalities and the house’s architectural style. A person who is drawn to clarity and simplicity may prefer paths that are direct and logical. By contrast, clients who want to show that they have many layers might opt for an intimate progression of spaces that lead people on a journey from one landscape experience to the next. To help clients visualize the possibilities, Messervy asks them to think of paths as a stream moving through a landscape. They flow around obstacles and form pools at the top and bottom of stairs and other transition points. At the front door, for instance, a path widens into a threshold so that a visitor can stop and put on lipstick or straighten a tie. The idea is to orchestrate the experience of moving, pausing, and stopping.

“The gesture of the path creates a flow that pulls the whole design together,” says Messervy, whose new book, Home Outside, is due out next January. “Even if you don’t make a path, one might be implied as negative space between planting beds. Sometimes I start deliberately, figuring out how to get from here to there, and then start playing with the line of where the path could go.” Materials, width, and shape are used to create hierarchy; paths on the public sides of the house are wider and more direct, whereas secondary paths are narrower, perhaps curvilinear and more natural in feel.

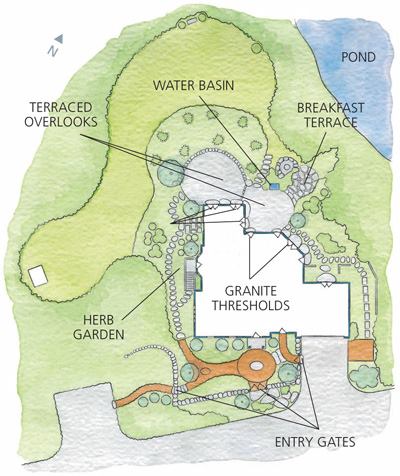

These principles are on display at a 1920s European-style house on a corner lot in a Boston suburb. After the house was enlarged and a garage added, Julie Moir Messervy Design Studio was called in to make sense of the outdoor circulation. Taking cues from a remnant brick courtyard, Messervy designed a large oval brick “welcome mat” with a granite center in the front garden. She manipulated the brick pattern so that paths radiate from it in three directions, organizing the entry options. The oval centerpiece is on axis with the front door and a gate through a 6-foot stone wall leading to the street. A second path connects the welcome mat with visitor parking to the left and forks off to stepping stones that lead to the rear herb garden and a large bluestone terrace overlooking a pond. In front, repeating the stone wall motif, Messervy then used flat, chunky stones to link the brick oval to a smaller brick path on the right that connects to a front service entrance and parking outside the garage.

While the formal brick paths spell out public spaces, the material choice was also practical. “I was trying to make it easy to shovel and walk the courtyard,” Messervy explains. “Anything that moves around the house doesn’t need to be shoveled, and the entertaining terrace in back is also easy to clear off.” Whatever the material, she advises using pieces that feel thick and stable underfoot. “Things need to be beefier in the landscape,” she says. Stairs should be at least 15 inches wide, with deep treads and low risers. Lay walking paths 2 to 3 feet wide; stepping stones can be slightly narrower. And pace them for a comfortable stride. Break up stepping stones with larger stones so people can stop and put two feet down.

Likewise, lines drawn outdoors must be bold. “There’s so much going on in the landscape in 3-D that anemic curves often read as mishandled straight lines,” Messervy says. “Big sweeping curves have energy.” When making a curve in the path, she often adds something that invites people to slow down and notice what’s at their feet, such as a beautiful tree or flowering shrub. At that point the path might balloon a bit into a pivot point or gathering place. Another favorite gesture of Messervy’s is to deploy elements that heighten the sense of journey. She accomplishes this by hiding the destination and placing clues along the way, such as odd pieces of stone that culminate in a rock garden, or tucking a small water basin into a path leading to a pool.

“It’s kind of fun to think about paths because they can be so many different,” Messervy says. “We want visitors to experience our landscape in a certain way. It’s about control in the best sense of the word, how it is that we want people to move around our property.”—Cheryl Weber is a writer in Lancaster, Pa.

Landscape designer: Julie Moir Messervy Design Studio, Wellesley, Mass.; Masonry contractors: Roger Hopkins Stone Sculptor & Associates, North Palm Springs, Calif., and Rico D’Eramo Masonry Contractors, Sherborn, Mass.