Just over three out of five first-time home buyers is a 35-year-old or younger. What’s more, according to the National Association of Realtors, the median age of first-time buyers is 32, older than it’s been since records have been kept.

The NAR observes, too, that first-time buyer households have a higher income ($72,000) than last year ($69,400), and tended to purchase a slightly larger home (1,650-square-feet; 1,620-square-feet in 2015) that was more expensive ($182,500; $170,000 in 2015).

And why not? These buyers–thanks to the slog of having to shed student debt, find decent-paying employment, and cobbled-together their own households paying higher and higher rent in the wake of the Great Recession–paid their dues by waiting, and want more.

So, just as the first leg of housing’s recovery served prominently to meet the needs of higher-end, discretionary, “want-to-have” buyers who could put their hands on a lot of cash and, in turn, get a lot of value for their early-moving real estate dollars, now comes the entry-level equivalent.

A first wave of buyers in the lower rungs of the housing price spectrum is the first-time buyer with the best credit, the best early track record of household income growth, the best tactics to rid the the baggage of college loans, and the most felicitous match up of household earnings and geography, where entry-level dollars go the farthest. This first wave of buyers is the more financially ready group of a larger more personally willing universe of would-be home buyers.

They’re the reason for the evolving appeal of “entry-level plus” home and community offerings that strike a balance between attainable pricing levels and aspirational design, features, and functions in their homes.

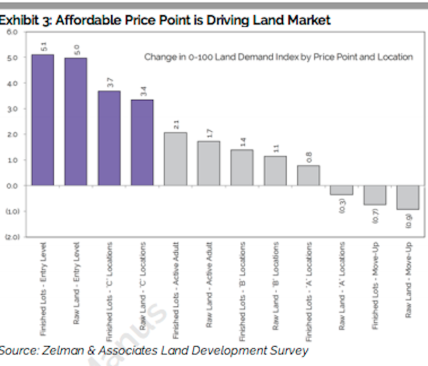

The NAR are not the only ones calling attention to the fact that first-time buyer households are back on track, heading slowly and steadily toward the 40% share of the home buyer market they’ve historically represented. In the latest edition of The Z Report, Zelman & Associates‘ bi-monthly drill-down into a series of topical analyses on the single-family and multifamily real estate investment and construction market, notes that a key leading indicator for single-family is neon-light flashing on entry-level as “the prettiest girl at the dance.” This assertion comes clear in Zelman & Associates proprietary surveys on home lot demand of the moment.

“Our overall land demand index was 0.6 points higher versus this time last year, led by entry-level finished lots (up 5.1 points), entry-level raw land (up 5.0 points) and finished lots in affordable C locations (up 3.7 points). Similary our index tracking the development of raw land reached 64.8 in 3Q16, another peak for this cycle.”

As Zelman’s team notes, the “lack of supply” is the No. 1 challenge to entry-level volume, and, by and large, builders have heard the clarion call of opportunity and have fairly started tripping over themselves to avail of it.

Which brings us the the subject of data. Those who have and use not “big data” but the right data are the ones who’ll enter the next leg of housing’s recovery and come out of it in better rather than worse shape. The right data. What does that mean?

Here, Harvard Business Review contributor Maxwell Wessell, general manager of SAP.io, looks at how most businesses–including home building and residential development firms–can zero in on and pivot around critically important “small data,” rather than plunging into the sea of potentially helpful big data. Wessell asks, “What decisions drive waste in your business?

Well, how about lots that are priced wrong for your product, or ones in a submarket that’s saturated with parity offerings, or ones whose geographical location stretch too thin your operational footprint, or lots that will wind up costing you more to bring them online than your profitability model can tolerate? What about lots whose product and community value proposition won’t achieve the pace that you need to generate the margins you need on your inventory turns? What about lots that are put in to a plan that don’t optimize your land return on investment? What about lots that, if mortgage lending tightens, will wind up just beyond this cycle’s path of growth?

In each of these areas, there’s risk of waste–of money, time, human resources, focus, etc. Wessell’s point is that the “right data” can help you automate decisions that reduce the risk of waste. He writes:

“When it comes to making simple, repetitive, operational decisions (like where to send a cab, how to price a product, or how many flowers to order to a floral shop), machines tend to be much better than people. And although many business models of the 20th century are predicated on human control of these decisions, today we can identify the data to automate more of these decisions than you’d imagine.”

Remember, before we see 40% first-time buyer share of the total home buyer universe, we’ll see a rise from 35% to 37%, and many of them will be “entry-level” plus buyers–at the higher end of the first-time home spectrum, where loan applicants can generally bring more cash, better credit records, and more monthly payment wherewithal to the table for that attainable-aspirational home.

That’s a tricky land position. It will take the right data to zero in on it, value it, and plan it for optimum returns. We’re betting that our success and failure stories of 2017 will consist largely of firms who do well–or not–at putting the right data into action.